When Jaiden Pax, a senior majoring in integrated studies at Augusta University, enrolled in a political science course called Race and Politics, she wasn’t sure what to expect.

“I feel like I have a firm grasp on how race impacts everyday American life, but I didn’t feel like I fully understood how much ingrained it is due to systemic racism,” Pax said of the class offered this semester by the Department of Social Sciences. “I thought that this class would teach me more about that, and I was definitely right.

“We’ve discussed everything from the pros and cons of gentrification on American cities to how the American poor are disproportionately made up of minorities. I’m from New York City, so those are some of the topics I’ve always been curious about.”

The Department of Social Sciences has never shied away from newsy topics that impact students’ lives on a daily basis. But this past year has opened the door to an entirely new set of courses that deal with current issues relating to race and politics, the social influences of fake news and information warfare, and the impact COVID-19 has had on health care, the economy and governments around the world.

“We really do care about students and offering them classes that we think will interest them,” said Dr. Mary-Kate Lizotte, an associate professor for the Department of Social Sciences in Pamplin College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences. “I think our current chair, Dr. William Hatcher, and our previous chair, Dr. Kim Davies, are always really open to offering classes like my Race and Politics course.

“It’s really wonderful to work with colleagues who are happy to offer a new class and put in that extra work to prep something that they haven’t taught before, just because they think there would be some student interest and it’s a timely topic.”

Not long after the death of George Floyd in the custody of Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin last May, Lizotte began thinking about creating a class relating to race and politics at Augusta University.

“Given everything that was going on with the Black Lives Matter movement and concerns about police brutality and racial inequality across the country, everyone in the department thought it was a really great idea and I was excited to teach it,” Lizotte said. “It was something new and different and it’s been really popular this semester. In fact, it’s cross-listed as an honors course and as a political science, upper-division special offering and the honors students ended up over-enrolling in the course, so that was exciting.”

While the current course is taught completely online due to the coronavirus pandemic, Lizotte said the students are still able to engage with one another using discussion boards to debate topics in class.

“It’s been really interesting because the students have shown that they’re able to talk about sensitive topics and express disagreement while also being tolerant and respectful,” Lizotte said. “This semester, we’ve already touched upon the issue of police brutality and also the issue of reparations and whether or not the United States government should make restitution for African American descendants of slavery.

“But we don’t just talk about race in terms of African Americans. We talk about other issues that are connected to race and ethnicity.”

For example, Lizotte said the class has discussed the Alternative Right, commonly known as the alt-right, whose core belief is that white identity is under attack by multicultural forces using “political correctness” and “social justice” to undermine white people.

“We’ve talked about alt-right and far-right extremism in connection to the events of the Capitol riots on Jan. 6,” Lizotte said. “We’ve also talked about things like gentrification and immigration, which is a big topic, and whether or not Dreamers should be given a permanent path to citizenship.”

Not only does the class discuss current topics, but it also addresses historic events that have shaped race relations in this country, such as the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1896 landmark decision, Plessy v. Ferguson, that upheld the constitutionality of racial segregation laws for public facilities as long as the segregated facilities were “separate but equal.”

The class has also discussed the topic of “rural white identity” and how some white Americans living in rural America believe urban areas are unfairly receiving the majority of government funding, Lizotte said.

“Those living in rural areas are experiencing an extremely difficult economic time right now,” she said. “It has become much more difficult for individuals who have less than or only a high school diploma to be in the middle class than it ever was before. That’s because a lot of the types of jobs that those individuals would have gotten, in terms of manufacturing, don’t exist anymore, either because of outsourcing or robotics.

“People living in rural areas really feel like government officials haven’t done enough to provide for policies and funding to help those areas stay afloat.”

These are the kinds of topics that some students may not expect to be discussed in a class about race and politics, Lizotte said.

“I’m assuming that students probably thought that the course was going to be centered on Black Lives Matter and issues like that, but in order to really understand what’s going on right now in current events, you really need to touch upon all these different topics,” she said. “You really need to have a comprehensive view, historically, from different segments of the population to see how those all touch upon one another.”

Pax, who is 27, said she and most of her friends follow current events and new legislation that is introduced in this country, but she has found a deeper understanding about those topics by taking Lizotte’s class.

“My friends and I, we are a very diverse group, so race actually comes up in our conversations very often,” Pax said. “A lot of us have strong ideas of how race affects us. But I’m also studying marketing, and this class actually helped me understand more about American economics and how race and politics can impact our consumer base.”

Pax said she would definitely recommend the class to other students in the future.

“This class helps you better understand American life and why we argue about the things we do and why certain arguments just don’t make any sense,” she said. “It actually offers a lot of clarity on your everyday life, so it’s been very beneficial to me.”

The economic impact of a pandemic

Dr. Dustin Avent-Holt, an associate professor of sociology at Augusta University, has been wanting to teach a course about the sociology of the economy for many years.

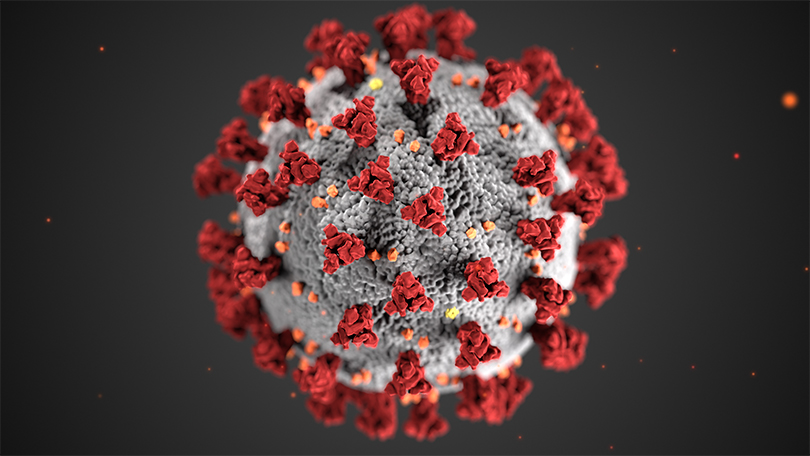

But it wasn’t until after the COVID-19 pandemic hit that he saw an opening to create a course called Economy & Society: Crises, Pandemics and Alternatives.

“When the pandemic hit, I thought, ‘OK, there’s a lot going on that’s connected to how we organize our economy socially and what the politics are that are underneath those decisions,’” he said. “I wanted to look at the political institutions that are in place that shape what the trajectory of the pandemic looks like in different countries.”

For example, countries such as Denmark have managed the pandemic while also providing social supports for individuals in their societies, Avent-Holt said.

“Denmark’s approach looks very different than what we did in the United States,” he said. “In Denmark, they had a robust kind of funding for employers. Basically, they subsidized everyone’s wages. So, instead of an employer having to pay for their employees’ wages out of the revenues coming in, the state was paying for the employees’ wages as long as the employer agreed they weren’t going to lay anybody off.”

As a result, Denmark provided its citizens financial support during the lockdown due to the pandemic, Avent-Holt said.

“Therefore, Denmark provided a kind of public health intervention,” he said. “They stopped people from interacting, but Denmark also provided social and financial supports to make that possible.”

It took several months before the United States provided its citizens with stimulus money to help support people during this economic and health crisis, he said.

“So, that got me really thinking, ‘How could students benefit from understanding the way that we’re responding to this public health crisis economically and how that shapes people’s lives and the economic opportunities that are out there?’” Avent-Holt said. “So, also in this course, we think about alternatives. For example, how could we organize our economy in such a way that it automatically provides this kind of social support for people?”

Comparing the ways in which different countries have responded to the COVID pandemic gives students a new perspective on economic issues facing the United States, Avent-Holt said.

“The students are learning and thinking about things that they may not otherwise,” he said. “They are asking questions like, what does this pandemic mean for working mothers who are trying to juggle a career, plus have their kids at home learning remotely? What does that do to gender dynamics? How are African Americans being more affected by this current pandemic?”

The course has appealed to students with a variety of majors such as psychology, biology, cell and molecular biology, chemistry, criminal justice, sociology and political science, Avent-Holt said.

“I think, especially for those students who are coming from a traditional health sciences or biology background, this is very exciting for them because I don’t think in a lot of their classes they talk about the kind of social consequences of what’s happening with people’s health,” he said. “So, this provides a space for them to kind of think about their own health-related major and how public health feeds back into thinking about the social organization of society.”

The coronavirus pandemic has had such a huge impact on the entire country that Avent-Holt believes this course will continue for many years to come.

“COVID-19 is not going anywhere. Of course, how we manage it is getting better. We will all, hopefully, be vaccinated in the near future and some sense of normalcy can return,” he said. “But students coming in, who are enrolling at Augusta University next year and in the years to come, they’ll have this as part of their memory. And I think it will be part of our collective memory in the way that something like 9/11 is part of our collective memory. Even if you weren’t born to have seen 9/11, you know about it and understand it.

“I think this pandemic will provide lots of avenues for more of these conversations going forward for many years to come.”

The sociology of health and illness

When the coronavirus pandemic struck last year, Dr. Elizabeth Culatta, an assistant professor in the Department of Social Sciences, saw it as an opportunity to reexamine the approach to her class on the Sociology of Health Care and help her students take a closer look at pandemics and the impact of COVID-19.

Last year, Culatta and her students focused on a variety of topics, including the history of pandemics, the effects of social isolation and the impact class and socioeconomics have on the treatment and testing for COVID-19.

This year, students in both her Sociology of Health Care and Sociology of Health and Illness classes have a much greater understanding of pandemics because, after all, they’re living through one.

“So, this year, I’m back to my regular curriculum, but a ton of their questions are about the COVID pandemic because we are all thinking about it all the time,” she said. “In my Sociology of Health and Illness class, one of our main vocabulary words is pandemic, and it was a word that students previously were not familiar with. They were like, ‘Pandemic?’ They were thinking of an old movie or something. And now, of course, it’s in every headline. I don’t need to explain it.”

Instead, Culatta and her students look at issues such as health disparities across race and class lines and how diseases such as COVID-19 have a greater impact on communities of color.

“We ask questions such as, why would someone be more at risk? Why would COVID then disproportionately impact those across racial and class lines?” Culatta said. “We also talk about vaccine hesitancy in the class. And students ask, ‘Should I get the vaccine?’ But some of them have really specific questions about which vaccine is better and what are the effects of the vaccine.”

COVID has provided her classes a unique learning experience because the situation is extremely fluid, she said.

“First off, the global pandemic is awful, obviously. But it’s also a great learning opportunity because the students have all these questions and some of the questions, I don’t know the answers to,” Culatta said. “I just encourage them to go to sources that will help as best we know, right now. After all, there’s a lot of things we don’t know.”

However, not knowing an answer shouldn’t be the end of the conversation, Culatta said.

“I’m just trying to teach them to ask questions to better understand what’s going on, even if it’s changing with each breaking news report,” she said. “The truth is, you cannot know all the answers, but you still can be asking really good questions. That’s the goal.”

Politics of a pandemic

Starting this fall, Dr. Lance Hunter, an associate professor of political science with a background in international relations, will be offering a course that will look at the ways governments around the world have responded to the COVID pandemic.

“We had a lot of different types of responses. Some countries had a very strong lockdown and strict quarantine measures, and others were not doing much at all,” Hunter said. “So, we decided to create a course and break it into a few different parts. First, we would look at how governments responded differently. Then, another part of the course would be, why did they respond differently? Is there something about these governments and these countries that are different that led them to respond differently?

“Finally, the course would focus on what effect has COVID and the pandemic had on domestic politics and nations and governments themselves. So, really, how have pandemics changed government?”

This approach will allow students to analyze the various approaches of democratic governance and authoritarian nations, Hunter said.

“What really motivated me to look at the course is my background in international relations and comparative politics, which examines different countries’ responses to issues. And then, also, my research in democratization. Basically, what leads nations to be more or less democratic,” he said. “In my research, any time there’s a national security issue that emerges where there’s a security threat like terrorism or something like a pandemic, that can have profound effects on domestic politics within nations.”

Hunter believes this course will appeal to a wide range of students, including those interested in political science, international relations, sociology and medicine.

“We will look at what countries were more or less successful in dealing with this because the approaches can vary by country and regions,” he said. “So, a student interested in studying disease, the spread of viruses and global health, they might be interested to study the different government approaches to this pandemic around the world.”

And the course will be constantly changing because, as this pandemic continues, students can continue to track the impact of each country’s approach, Hunter said.

“I could teach this course in the fall of next year and then by the spring, just a month or so after the course ends, you could have a totally different perspective,” he said. “So, I’m really excited about this course and, hopefully, students with a lot of diverse backgrounds, perspectives and majors will sign up for the class.”

The impact of social influence

For the past several years, Dr. Craig Albert, director of the Master of Arts in Intelligence and Security Studies (MAISS) program at Augusta University, has been working to develop a new concentration in social influence and persuasion.

He was recently thrilled to announce the new concentration has been approved and it will be offered this coming fall.

“This new concentration focuses on propaganda, fake news, information warfare, social media and the weaponization of social media,” Albert said. “The need for this concentration was brought to our attention through participation in collaborative conversations between internal and external stakeholders. They thought that this was an interesting issue and noted that there weren’t any concentrations focusing on it yet. They highlighted the fact that there was across-the-board need for this kind of curriculum.”

Monty Philpot, the director of federal relations for Augusta University and AU Health, organized several meetings with different stakeholders within the U.S. Department of Defense, academia and industry to discuss the need for this new concentration, Albert said.

“Over a series of conversations, we discussed what classes would most benefit the DOD personnel. We asked, ‘What are they missing that we could provide?’” Albert said. “We created the four classes based on all of those conversations.”

Albert said the four courses include cross-cultural security and psychology; open-source intelligence; the history of weaponizing social media and the theory of propaganda; and information warfare.

“The purpose of the cross-cultural security and psychology class is to see how our strategic adversaries think and look at us as Americans, and how we as Americans think and look at stereotypes or frame different cultures,” Albert said. “We want to understand how we actually operate in that realm and how others look at us and we look at them, because that can help alleviate a lot of tensions that might cause war in the future.”

The course on open-source intelligence will concentrate on social media analysis, Albert said.

“Basically, we’ll look at, how do you collect info off Twitter and really establish a profile of somebody,” Albert said. “Russia did this on former President Donald Trump. They established a psychological profile of Trump just by combing his Twitter feed and putting everything together and having a psychiatrist analyze it. They did that just from open-source intel on his social media accounts, which is terrifying if you think about it.”

The third class will be the history and theory of how propaganda operates from the dawn of the enlightenment through social media analysis today, Albert explained.“And, finally, the course on information warfare will look at how it works and how it has worked through history,” Albert said. “I’ll teach that course and I’ll focus mainly on social media warfare as well and fake news and propaganda. Basically, all of the stuff that we see online with fake accounts being created and really spreading false misinformation and disinformation. And all of the classes will try to keep the focus on our strategic adversaries, such as North Korea, Iran, China, Russia and ISIS.”

Even though the new concentration was just recently announced, Albert said he’s already received a lot of positive feedback from students interested in the courses.

“Our undergrads are already interested and all the students in the master’s program are pretty bummed that most of them are going to graduate before that concentration is offered,” Albert said, chuckling. “But the partners we have talked to are really excited about the idea of this. And the Georgia Cyber Center is totally onboard with it because we recently established the Georgia Cyber Information Warfare Internship with them as well.

“Basically, if you are a student in our MAISS program and you are approved by me and the Georgia Cyber Center leadership, you can receive an internship and get to do state-of-the-art innovative research on information warfare.”

This new concentration and the internships available through the Georgia Cyber Center have made Augusta University a leader in this field, Albert said.

“We are becoming the university known for its instruction on information warfare and social influence,” Albert said. “When we created this concentration, there was no program established like it that I could find in the country. There were classes, here and there, but nothing like a concentration embedded in this type of field.

“This is pretty unique and innovative, so I can’t wait to have our first group of students start this fall.”

Augusta University

Augusta University