From time to time, the news reports blood shortages. Shepeard Community Blood Center regularly hosts blood drives across the area. Frequently, The American Red Cross reminds us that “every two seconds, someone needs blood.”

Blood donors know they are doing a good deed when they donate. Most people are quite familiar with blood donation, if not the process by which it is collected, processed and stored until it is needed.

That’s all thanks, in part, to a man named Virgil Sydenstricker, who was an influential physician and teacher at the Medical College of Georgia for more than 30 years.

History of blood donation

In the early part of the last century, the process of blood donation looked a lot different. Because blood clots as soon as it leaves the body, it couldn’t be saved to be transfused into another body at a later time. Therefore, blood transfusions occurred directly from the donor to patient.

It was a complicated process, and physicians of the time were working to find a better way. In June of 1917, Sydenstricker — at that time a young intern at Johns Hopkins University — published an article explaining that the ideal method of transfusing blood was to add citrate to keep blood from clotting. This would allow the blood to be stored and used at a later date. His method revolutionized the then-current methods of transfusing blood from person to person.

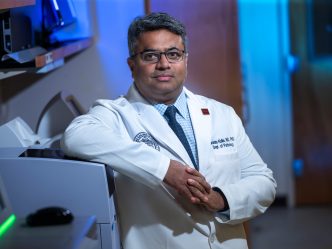

“I don’t know how much they knew about the clotting cascade at the time, but it turns out that much of the cascade is regulated by calcium. And so if you can bind up the calcium, then your clotting cascade doesn’t function,” said Dr. Roni Bollag, director of the biorepository at the Georgia Cancer Center at Augusta University.

Bollag said citrate is highly effective at binding the calcium to keep blood from clotting. That means the citrated blood remains in liquid form, can be stored for up to six weeks and transfused into a patient when needed. Because it is a naturally occurring compound, there are few side effects when infused into a patient.

“It turned out to be really ideal, and it’s still what we use,” Bollag said.

Sydenstricker’s article went on to explain some of the adverse effects of frequent transfusions, one of the earliest articles to do so, Bollag said.

“The patients they were transfusing are patients that were getting many transfusions, and clearly he realized that they were developing antibodies or something else, which we now know was the case. This is a great technique but you need to watch out for adverse reactions, and I thought that was also very foresighted,” he said.

Three years after publishing his article, Sydenstricker joined the faculty at the Medical College of Georgia, and became one of the most influential physicians to the institution and to Georgia medicine. During his career, he discovered that niacin cured and prevented pellagra and other vitamin deficiencies, founded the sickle cell clinic still in operation at Augusta University Health, and oversaw the nutritional care of troops and former prisoners of German prison camps during World War II. By 1958, he had trained two out of five practicing physicians in Georgia.

Sydenstricker’s early work in blood transfusion continues to influence the banking of other biological specimens at Augusta University.

Blood and tissue banking

Typically, when blood is taken from a donor, it is spun in a centrifuge to separate out the desired components, which are tested and stored as units. Sometimes the desired component, such as plasma, is studied to determine which antibody is causing a patient’s disease. The plasma is citrated and can then be frozen in the biorepository for later study.

Researchers are interested in studying samples of plasma — or red blood cells, white blood cells, or other blood products — from different patients to compare diseased cells to healthy ones. The citrating process keeps these products viable for study.

This process has also led to the development of storage processes for other types of tissue. Augusta University’s biorepository in the Georgia Cancer Center banks blood products, but it also stores tumor samples, along with healthy tissues.

“Any tumor that you can actually imagine we try (to get it) if there’s extra tissue left over, if it’s not needed for diagnosis,” Bollag said. “We try and get a piece of that. So we have kidney tumors, we have lung tumors, we have bladder tumors, we have prostate tumors, we have brain tumors — pretty much anything. We keep an eye on the surgery schedule, so if there’s an interesting case… And the surgeons are on board. They know we’re interested in saving some of these samples because they know how useful it is.”

Banking of human samples has been practiced for many years and the Georgia Cancer Center Biorepository has been in operation since 2005. Nearly 35 years after Sydenstricker and his colleagues published their seminal article at Johns Hopkins, some of the most famous banked samples were collected there, including the ubiquitous HeLa cells — cervical cancer cells that were harvested and reproduced from patient Henrietta Lacks in 1951 that continue to be reproduced for research.

Since then, tumor samples have remained a great source for research, but the process has changed significantly, with a focus on protecting and properly informing the tissue donor.

Bollag said any surgical material is of value, so normal tissues are also stored for comparison. Ideally, samples are taken from both a tumor and the tissue it has affected. However, in some cases, such as in gynecological cancers, the healthy tissue becomes so compromised that saving a piece of healthy tissue from the same patient isn’t possible. Therefore the biorepository stores benign hysterectomy tissues or samples from a variety of non-cancerous surgeries for researchers to use as a control, or normal reference point.

The biorepository

The Georgia Cancer Center Biorepository has also collected samples from as many as 15 sites across the state, in addition to Augusta University Medical Center. Blood and fluid samples are stored in freezers that resemble large, upright kitchen freezers in the biorepository. A separate room contains several cryofreezers filled with liquid nitrogen to keep specimens frozen between minus 170 and minus 196 degrees Celsius. Each cryofreezer can hold more than 20,000 specimens and is self-monitoring to keep them stable.

Donations are all voluntary. Patient consent is obtained for each sample collected — the biorepository has an entire team dedicated to obtaining patient permissions to save samples from their surgeries. Bollag said people are often amenable to allowing their samples to be saved for research.

He even has favorites, collected from two patients with terminal cancer who requested their tumors be donated for research.

“That’s a true gift,” he said.

Augusta University

Augusta University