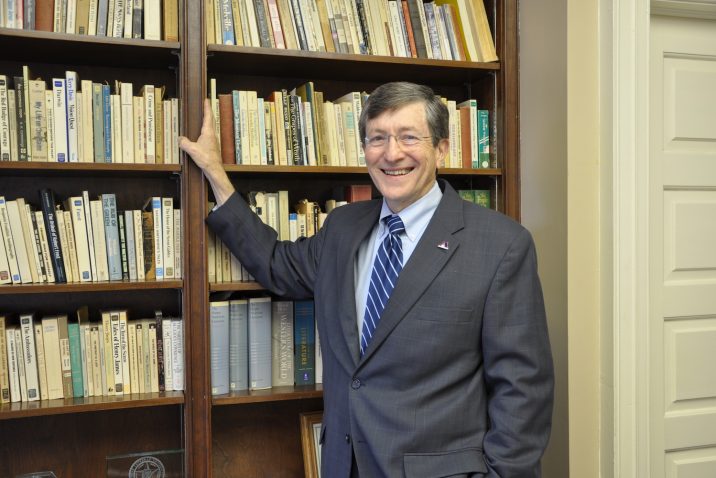

President Emeritus of Augusta State University William A. Bloodworth Jr. never forgot a name or a face.

He wanted to know you. He wanted to learn about your background and meet your family. But most importantly, he wanted you to feel at home at Augusta University.

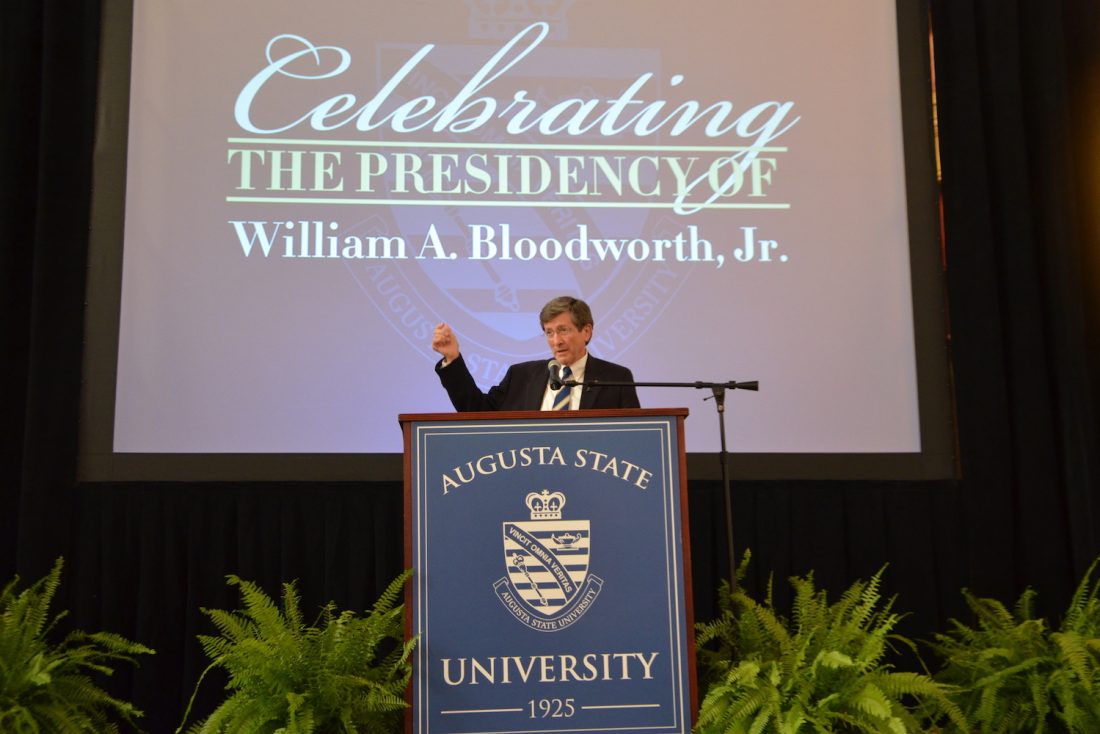

Bloodworth, who oversaw Augusta College’s transition to Augusta State University and served 18 years as president starting in 1993, passed away on Monday, Aug. 29 at 79.

Just before he retired as president of then Augusta State University in 2012, Bloodworth talked with Dr. Lee Ann Caldwell, a professor of history at Augusta University, about his approach to leading the university.

“I’d like to think that maybe I’ve shown that you can be a relatively effective president without being hard-nosed about things,” Bloodworth said during the 2012 interview, adding that he prefers spending time getting to know people.

“I have notes on every new faculty member every year because I want to know everyone who works here. I really wanted us to continue this sense of family that we had. I walk around campus all the time getting to know people, knowing always I’m being seen as the president, the leader.”

Augusta University President Brooks A. Keel, PhD, said this week that the entire university community is deeply saddened by the passing of Bloodworth.

“Alongside a teaching career that spanned half a century, Dr. Bloodworth was instrumental in our institution’s growth, overseeing Augusta College’s transition to a state university, developing new programs, accreditations and online class offerings, as well as spearheading over $103 million in new construction and renovations during his tenure,” Keel said. “We have him to thank for many of our Summerville Campus buildings, including Allgood and University halls, the Jaguar Student Activities Center and student art facilities, as well as our athletics golf facilities.”

“Dr. Bloodworth’s commitment to student success and accessible education sets an example for all of Jaguar Nation as we fulfill our mission to serve students not only in Augusta, but throughout the state of Georgia.”

Survivors include Bloodworth’s wife of 57 years, Julia Rankin Bloodworth; son Paul Bloodworth (Catherine); daughter Nicole Bloodworth (Dana Meyers); grandchildren Palmer, Sara Jane and Molly; and Bloodworth’s beloved King Charles spaniel, Ollie.

Love of people

Those who knew Bloodworth best have shared memories this week that have brought laughter, tears and hugs between colleagues.

Bloodworth, who became the eighth president of Augusta College, was widely admired for his teaching and leadership skills and beloved for his humility and his humanity, said Judy Cooke, his former executive assistant who began working for him in 2005.

“He was a remarkable man filled with joy,” Cooke said. “He loved people. He knew people. When new faculty would come on board, he would send them an email and he would ask them, ‘What are your career expectations? Where do you see yourself in 5 to 10 years?’ He would get to know their family and ask about them. I mean, he did his homework because he cared about everybody he encountered.”

Bloodworth’s pride for Augusta University overflowed each day and he openly celebrated the triumphs of all staff, students and faculty.

“I can remember during our time when we went to the Elite Eight in 2008,” Cooke said, laughing. “Just before the games, he would get blue hair spray and I would spray his hair a bright blue and he’d spray mine. We were a family, and I believe that Bill Bloodworth was the reason for that close bond.”

“But he never took credit for anything. Never,” she added. “And he always rejoiced in other people’s accomplishments. When people were sending emails, he was always writing personal notes. He was just that kind of man.”

Clint Bryant, the former athletic director at Augusta University, recalled Bloodworth — blue hair and all — jumping on a bus filled with students and riding 15 hours to attend the NCAA Elite Eight that year.

“He had a close connection to the students,” Bryant said. “There’s no doubt his legacy at this university will be something that goes on for years. He was always just a tremendous person, as much as a tremendous leader, and he made me and everyone around him feel special. He always took the time to visit, talk and have a laugh.”

During his tenure, Cooke remembers that Bloodworth had asked that those who worked for university facilities be given shirts with their names printed on them.

“I remember one day someone was in our building cleaning and she joked with him that she didn’t know if having her name on her shirt was a good thing. She thought that people wanted their names on their shirts so they could complain,” Cooke said. “Dr. Bloodworth quickly went up to her and explained, ‘No. You know who I am, I want to know your name.’

“A few years later, upon his retirement, the staff from facilities invited him to a little celebration of their own and presented him with a custodian shirt with his name on it. That shirt meant the world to him.”

Dr. Jim Garvey, professor emeritus of English and journalism, came to Augusta College in 1979. Over the years, he worked for several different presidents, but Garvey said there was a warmth to Bloodworth that he had never experienced before.

“He went out of his way to treat everybody with the same respect,” Garvey said. “He did not believe in some hierarchical system, whereby, we, the faculty, were more worthy than those who cut the grass and planted the flowers. He knew everyone and treated everyone the same. It was wonderful.”

Nancy Childers, who was his executive assistant when Bloodworth began in 1993, said every decision he made was for the good of the students, faculty and staff.

“I will never forget before he came to campus after he had been selected as president, he called me and said, ‘Nancy, could you get me all the names of the people on campus?’” Childers said, chuckling. “And I said, ‘Everybody?’ And he said, ‘Yes, please. Everyone.’ I got all those names and I sent them to him. Right away, he went to work trying to learn everybody’s name before he ever got there.”

When he would meet someone new, he would paste their names up in his office so he would remember them, she said.

“I had never worked for a president before who made that much effort,” she said. “He took the time to do the little things that meant the world to people. And it wasn’t for show. He was genuine.”

A natural teacher

Born in San Antonio, Bloodworth’s childhood wasn’t easy after his parents divorced. He attended five different elementary schools as his mother moved around looking for work. It wasn’t until he enrolled in a tiny school in Wilson County, Texas after moving in with his father and stepmother that he found his love of learning from his teacher, Dain Higdon.

Bloodworth would go on to obtain a bachelor’s degree in English and education from Texas Lutheran University in Seguin, Texas, a master’s degree in English from Lamar University in Beaumont and a doctoral degree in American civilization from the University of Texas at Austin.

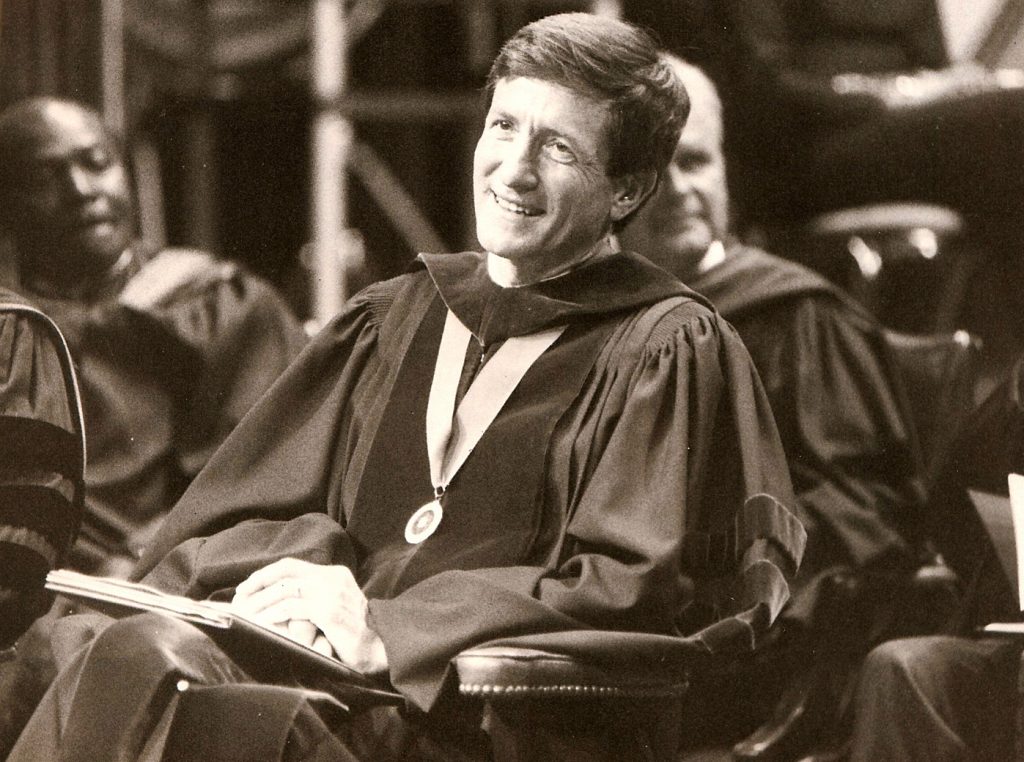

During his inauguration as president of Augusta College, Bloodworth personally thanked Higdon, who traveled with his wife all the way from Texas to attend the ceremony in 1994.

“In 1954 and 1955, I attended a small country school house in Wilson County, Texas,” Bloodworth told the crowd. “The school had four rooms, four teachers and eight grades. One person taught both the seventh and eighth grade — all subjects — in one of those rooms and served as the school principal. Through his example, he also taught me the nobility of teaching.”

Bloodworth asked Higdon to stand and be recognized for the positive influence he had on a “small Texas boy 40 years ago.”

“I hope that in my own career I have been able to pass on to others some of the respect for teaching and learning that were Mr. Higdon’s gifts to me,” Bloodworth said. “I am certainly pleased that my chief business in life is still teaching and learning.”

Dr. Lillie Butler Johnson, the former chair of the Department of English and Foreign Languages for 20 years at Augusta State University, recalled when Bloodworth, as president, drove her to University of Georgia to receive the Trailblazer Award several years ago. It was an award that she believes he secretly nominated her to receive.

During the trip, Bloodworth spoke of his childhood and when he discovered his love of teaching.

“We talked all the way to Athens and back to Augusta. He spoke of his surprise at his father’s insistence that he, a son with other plans, go to college,” Johnson said. “I thought, ‘Your father was right.’ Perhaps the first years in college positively influenced his whole career. President Bloodworth always advocated for students. He championed them. In the later years of his tenure as president and after his retirement, he taught. He loved teaching.”

But he also loved his job and the people throughout the university, she said.

“He appreciated people who worked for the university — groundworkers, housekeepers, staff, faculty, administrators and alumni,” she said. “In the broader community, folk from all walks of life respected and liked him, as he did them. He will be missed by everyone fortunate enough to have known him.”

Garvey, who worked with Bloodworth for decades, was amazed when he decided to return to the classroom after retiring as president in 2012.

“He insisted on continuing to teach because he loved students and sharing his knowledge and enthusiasm with people,” Garvey said. “Even when the COVID pandemic hit, which sent a lot of teachers packing, especially older guys like me, Bill stayed. He continued to teach. In his soul, he was a teacher.”

Dedicated to students

Dr. Andrew Goss, a professor of history at Augusta University, was chair of the Department of History, Anthropology, and Philosophy from 2014 until 2021 and worked closely with Bloodworth.

Every semester from 2014 until this year, Bloodworth taught two sections of the introductory History of the United States Since 1877 course, Goss said.

“Although formally retired, and after 18 years as president of Augusta State University, and an administrative and teaching career before that, he certainly did not need to spend two days a week teaching general education courses,” Goss said. “He confided to me that teaching kept his mind sharp, and brought him full circle back to the beginning of his career as a public school teacher in Texas.”

Students raved about Bloodworth’s classes, he said.

“Dr. Bloodworth was inspiring, funny, compelling, passionate about history and completely devoted to his students,” Goss said. “It’s no surprise he was one the most popular instructors in the department, with his classes filling to capacity shortly after registration opened. It was a privilege and honor to have him as a colleague. In the history program, he leaves a rich legacy as a teacher and instructor, as well as an academic leader and administrator. I will miss him dearly.”

Helen Hendee, the former vice president for Development and Alumni Relations at Augusta University, worked for Bloodworth for 18 years and saw firsthand his devotion to education.

“First and foremost, he was an English teacher. He loved teaching and being with his students,” Hendee said. “Becoming a president gave him more opportunities to serve our students.”

When Dr. Ruth McClelland-Nugent, chair of the Department of History, Anthropology and Philosophy at Augusta University, found and read Bloodworth’s inaugural address in 1994, she was particularly struck by one line: “The accomplishments of a college lie in the lives of the students it has served.”

“I wasn’t around to hear him deliver it, but I’ve watched him live out that belief ever since I got here in 2005,” McClelland-Nugent said. “Dr. Bloodworth’s love for the students we serve was clear from his work as president and later, from his work as a teaching professor in the introductory U.S. history classes he taught for our department.”

Bloodworth was much beloved and respected by students, faculty, and staff alike, she said.

“Coming from a working-class background himself, he had a strong belief in the transformative power of education, and in the unique role of higher education in creating opportunity,” she said. “He wanted Augusta College, and then Augusta State University, to be a place where diverse members of the community could come together in pursuit of learning.”

His vision was inclusive of all students, she said.

“He really wanted education to be accessible to all, and for all students to see themselves in the story of American history as he taught it,” she said. “He asked me once, colleague-to-colleague, for a recommendation of a book he could assign that would include more women’s stories, as he felt he wasn’t including enough in HIST 2112.

“I recommended a book about women in World War II called Our Mothers’ War. He thanked me and went off to read it, and liked it so much he was still assigning it to students the last semester he taught for us this past spring.”

Making a difference

Twenty-five years ago, Bloodworth worked diligently to name Washington Hall at Augusta University in honor of Drs. Justine and Isaiah “Ike” Washington, two lifelong educators and dedicated community leaders in Richmond County.

It meant the world to Bloodworth, McClelland-Nugent said.

“My proudest accomplishment as president came in 1997 when I was able to convince the Board of Regents to allow us to rename the College Activities Center as Washington Hall, after Justine and Ike Washington, leaders in the Augusta African American community,” Bloodworth wrote McClelland-Nugent in an email earlier this year. “For almost twenty years Ike Washington was a member of the Augusta City Council, and Justine was the first African American woman to serve on the Richmond County Board of Education.”

Due to a generous donation by the Washingtons to the Augusta College Foundation, Bloodworth was able to receive approval by the Georgia Board of Regents to rename the building.

“I can still recall the day when Ike and Justine came to my office to hear me explain the importance of having a building on campus named after one (or more) African Americans,” Bloodworth wrote. “They understood me exactly, and actually agreed to turn over their house, upon their deaths, to the then Augusta College Foundation. It took some convincing in Atlanta to get the approval, but we got it. And when we conducted the ceremony to rename the building, hundreds of local African Americans attended. It was a great day for the school.”

Bloodworth was a leader in every sense of the word, said Dr. Seretha Williams, chair of English and World Languages at Augusta University.

“Washington Hall is the only building on campus that recognizes the contribution of African Americans,” she said. “Also, Dr. Bloodworth’s Augusta University Endowment recognizes and awards staff who work in Facilities Services, faculty who teach part-time and students who need financial assistance to complete their degree.”

The legacy of Bloodworth will live on because of his deep devotion to the university, she said.

“Dr. Bloodworth was an exemplar of transformational leadership. As president, he prioritized people in all of his decisions,” Williams said. “He knew the names of students, staff and faculty. He even knew the names of family members. He had an open-door policy and faculty left his office knowing that he had heard and understood their situation.”

Remembering the man

Dr. Kim Davies, dean of Pamplin College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences, remembers when she was first interviewed at then Augusta College in 1996.

“Dr. Bloodworth was part of my interview process,” Davies said, laughing. “It was overwhelming to have the president of the university sitting in on the interview for a position at that level. But I remember the next time I saw him, after I accepted the job and the semester had started, I was at Arts in the Heart in downtown Augusta. I saw him and I was like, ‘Oh, he won’t know me.’ And the next thing I knew he was like, ‘Come over here, Dr. Davies. I want to introduce you to some people.’ And he told them that I went to Ohio State and what I studied. He knew everything and I was stunned.”

Bloodworth simply had a special way of making everyone feel at home, she said.

“Honestly, Dr. Bloodworth is why a lot of us stayed here,” Davies said, smiling. “I mean, so many of the people here were so kind to each other and his leadership style encouraged that.”

Dr. Wesley Kisting, associate dean of Pamplin College, joked that, while Bloodworth wasn’t involved in his interview process in 2007, shortly after he started at then Augusta State University, he was asked to join the first Leadership ASU class.

“I didn’t even know what it was, but I joined and it turned out it was this yearlong process where we went to every unit and department on campus,” he said. “Everybody in the class with me had been here a lot longer and was much higher up, so I just felt completely out of place. But Dr. Bloodworth just made me feel so included and would even walk over to my office and just come in and sit down and chat with me every once in a while.”

At the end of the course, Kisting told Bloodworth that, by learning about all the different aspects of the university, the Leadership ASU class changed how he approached teaching students. As a result, Bloodworth asked Kisting if he would present on that topic at a conference in San Antonio.

“I agreed and he had asked me beforehand if I’d ever been to San Antonio. I told him I hadn’t,” Kisting said. “Well, he took me all over San Antonio, which is where he grew up, and he was the best tour guide you could ever have. He just was so kind to me, to make sure that I was comfortable and had a good experience the whole time I was there. That’s what was so remarkable about his leadership style. I’ve never met somebody so down-to-earth and so people-centered with no hint of presumptuousness or ego. He just really enjoyed engaging people.”

Dr. Rhonda Armstrong, a professor in the Department of English and World Languages at Augusta University, said she’ll never forget the first day she met Bloodworth at the new faculty reception several years ago.

“He came up to me and saw my nametag and started asking me about my work and my research,” Armstrong said. “I was surprised, but I thought, ‘He and I both have PhDs in American studies and we both went on to be English professors, so our teaching and research overlap.’”

Armstrong remembered how engaged and interested he was in their discussion, but she just thought it was because they had similar backgrounds.

“But then he turns to my husband, Brian, who was also a new faculty member at the time, and he reaches into his jacket, and pulls out this kind of beat-up paperback book by the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein,” Armstrong said, laughing. “That is the philosopher that my husband wrote his dissertation on. I was looking around this room full of new faculty, and I was like, ‘How many books does he have in his jacket?’”

Armstrong paused a moment as the emotions of the memory swept over her.

“He just made a point to know the new faculty and to talk to us,” Armstrong said. “He really gave the sense, I think, to everybody, that not only he loved his job here, but he truly loved the university. And he wanted you to love it, too.”

Augusta University

Augusta University