Life – not the kind of life we see on screens, but the kind of life we actually live – isn’t supposed to come full circle. Real living is too messy, too unpredictable, to allow for even the most simple symmetry. And yet, sometimes the stars align and something happens that actually falls in line with the kind of life a screenwriter would have us live, the kind that drapes down with such poetic order.

Screenwriters, though – while they’re good with rhythm and design, to get the emotions necessary to tell the kinds of stories we want to hear, those stories where coming full circle tops things off with that crowning, unimaginable evidence of a greater, more artistic hand, they’ve got to do things with us that we’d never allow them to do. To get there, they’ve got to take us places we’d never voluntarily go.

So in that respect, even though we might enjoy stories like Rachel Taylor’s, stories that are tied together with such a neat and tidy bow, we ought to thank our lucky stars that we’re living the messy, unraveling lives we’re living, because one thing is for sure: while Rachel Taylor’s parents appreciate the way her life has come full circle, they’d never, never, wish the journey on anyone.

Rachel was diagnosed with hearing loss at the age of two. Hearing loss at two is rough, of course, but when those are the cards you’re dealt, you make do, even when there are no explanations or reasons. You figure out ways of getting by, and that’s just what Rachel did.

By the time she went in for her yearly check-up as a 6-year-old, though, there was something else. Something she called “the dizzies.” Her physician wanted to order an MRI to see if there was any connection to her hearing loss, but Rachel’s mother wasn’t sure. A post transplant social worker at what was then MCG Health, she knew MRIs were traumatizing, and she didn’t want to subject her little one, her only child, to a scary procedure if it wasn’t absolutely necessary.

The physician, however, said it was. Absolutely necessary.

“He said we had to,” Gloria Taylor says now. “And that’s how the tumor was discovered.”

The tumor. Everything – everything – changed with the tumor.

They went from diagnosis to surgery within a week. A week to go from normal life to the ICU. And after that week, Rachel spent two and a half more months at the Children’s Hospital of Georgia. Two and a half months of surgeries and setbacks and tiny, tiny victories.

“We had a different problem every day,” Gloria says. “Literally, every day we thought we’d be going forward and we’d take two steps back instead.”

Rachel, however, was a fighter. A tough kid who managed to dig in her tiny heels with each setback.

“Thankfully, I don’t have too many memories,” she says now, 12 years later.

And that’s the thing about illness and hospitalization – it doesn’t just happen to the patient. The pain and uncertainty and fear and everything else – and it’s a lot – is shared among the family. And when you’re 6 and your family is as close as Rachel’s, it’s shared very intensely.

Rachel’s mom remembers it all, though some of it she’d like to forget, even though she took albums of photos to make sure she never would.

And Rachel understands.

Practically, there’s no way she or any of them cannot be reminded of the tumor that was removed. An outstanding student, a senior at Greenbrier who’s a member of the National Honor Society, Beta Club, the Model UN, the school chorus, the church handbells and so much more, Rachel is blind in her left eye and deaf in her left ear, and part of her face remains paralyzed by the tumor.

The tumor and what it did to her is evident every single day, but its effects go so much deeper. Something like this – Gloria calls it an odyssey rather than a journey – seeps into a family’s lore, and Rachel knows all the stories. How her father would visit every night after work and how her mother, who had returned to her job just a month before the diagnosis, had to quit for five months in order to take care of her. Her job was there for her when she got back – she’s now a post transplant social worker at Augusta University Medical Center – but at the time, it was one of many blows suffered by them all.

And the party they threw when she finally left the hospital – that party celebrated a milestone, not an end. When she left the hospital after those two and a half months, she couldn’t walk, she couldn’t use her left arm. She couldn’t even swallow.

She entered the hospital in January and didn’t finish up rehab until December. You don’t lose a year like that – in that way – and have it not affect you.

And in doing that, she learned even more about what her parents went through.

“I had never explicitly just thought about the parents before,” she says. “So it was really – I don’t even know the word to describe it. It was just really cool to finally see their side.”

For what’s called the project extension of her senior project, she made comfort kits to be given to parents who, like hers had, find themselves in the children’s hospital with no thought for themselves.

The kits contain toothbrushes, toothpaste, travel-sized Kleenex, shampoo and other things parents of hospitalized kids might need but probably didn’t pack. And a notepad. Gloria remembers how important having a pen and a notepad was when it came to keeping up with the torrent of information that was thrown at her, so Rachel included a notepad, too.

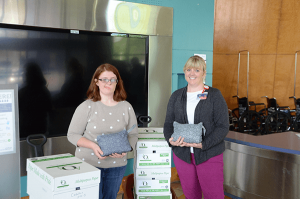

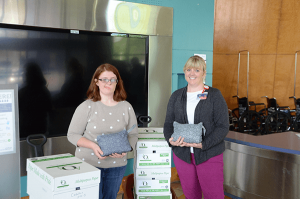

The cool thing, though – the way Rachel’s story comes full circle – is that the person she delivered these kits to last Thursday, the child life specialist she job shadowed, is the very same child life specialist who took care of her when she was sick all those years ago.

After receiving the boxes of comfort kits, Katie loads up a couple of wagons and wheels them upstairs, and in a way, that’s that. For most high school students in Columbia County, completing their senior project is a harbinger of graduation, one of the last checkpoints before wrapping up a childhood and gearing up for what comes next.

For Rachel, however, it’s something a little bit more. For her, moving forward has allowed her to circle back to something important. And for Gloria and Katie, looking back has given them a chance to see just how far she’s come.

For information about donating to CHOG, contact Stephanie Grayson at 706-721-4392 or email her at sgrayson@gru.edu.

Augusta University

Augusta University