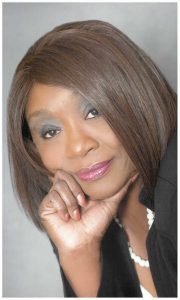

Back in September of 1967, a young, African-American woman named Lillie Butler walked across Augusta College’s campus for the very first time.

Even though she had spent her entire life in Augusta, she never imagined Augusta College would be a possibility for her.

“I can remember passing by the campus as a child because my brother’s godmother lived over on Fleming Avenue, but it was as if the college was invisible to me,” said Dr. Lillie Butler Johnson, the same young woman who later became the chair of the Department of English and Foreign Languages at Augusta University. “Augusta College wasn’t an option. It was not integrated, so it wasn’t in my imagination or thought.”

She was much more familiar with Paine College, where her father had graduated from college.

“Paine College was the college that I knew,” Johnson said. “I had attended concerts, plays and graduations there.”

It wasn’t until a representative from Augusta College’s admissions office came to talk to her senior class at T.W. Josey High School that she began to realize doors were opening at Augusta College, as the school was becoming integrated.

“I was looking forward to college. I’ve often said, I would have gone to college no matter what. I was hungry for it,” Johnson said. “However, when the recruiter came to my high school, he talked largely about all the obstacles and challenges of coming to Augusta College. He was discouraging.”

Johnson recalls her father, who was a school principal in Richmond County at the time, argued with the recruitment officer. He pointed out that Augusta College was a state-supported school and the seniors in the room had every right to attend.

“That September, I enrolled,” Johnson said, referring to the fall semester of 1967. “It wasn’t as if we planned it or my family did a lot of debating about it. My parents didn’t opt for me to go there. I opted.”

And even though she faced some discrimination in the late 1960s on campus, Johnson said she always felt she could succeed at Augusta College.

“I can remember standing in line waiting for an English class during registration of my first semester. The professor on duty said, ‘You must have a certain SAT score to take that course during your first semester,’” Johnson said. “I told him, ‘I have that score.’ Then, he said, ‘All the classes are closed.’”

What could have been a terrible moment in her college career was completely turned around by one man: then-English Department Chair Bill Quesenberry.

“He intervened saying, ‘If she’s an English major, put her in the English class,’” Johnson said. “That was a small gesture, but it’s often the little things that one remembers. I recall thinking at the time, ‘I can make it here.’”

When she began attending classes in 1967, Johnson was one of just a few African-American students enrolled at Augusta College.

“There were so few African-American students on campus that you pretty much knew the names of all of the students who were there,” Johnson said. “I will say this, to succeed, you had to be a pretty good African-American student at the time. And I was fortunate. As a good student, I longed ‘to know the best that has been said and thought in the world,’ as critic and poet Matthew Arnold put it.”

Also, as the child of two educators, Johnson said she felt comfortable in the classroom her entire life.

“In fact, I owned a carrel desk in the library on campus,” Johnson said, chuckling. “That seat belonged to me.”

While at Augusta College, Johnson also found not only a mentor, but a true friend in one of her professors, Dr. Adelheid “Heidi” Atkins.

“I took two courses in British literature from Dr. Heidi Atkins, romantic poetry and Victorian literature. She really inspired me,” Johnson said. “Those two areas became my major fields of study in graduate school. Dr. Atkins wrote one of the two recommendations that helped me enter graduate school, and we later became lifelong friends.”

In 1971, Johnson graduated summa cum laude and valedictorian of her class at Augusta College and went on to receive a master’s degree in English from the University of Chicago and a doctorate in English at the University of Georgia.

A few years later, Johnson found herself again leading the way after she was hired as one of the first two African-Americans instructors to teach full-time at Augusta College.

“Most of the students had not had an African-American teacher. It was the early 1970s in Augusta,” Johnson explained.

One evening, Johnson was reassigned to teach a course previously scheduled to be taught by a popular white male teacher.

Upon her arrival, one student asked, “You’re our English teacher?” prior to exiting.

That was the first night of class.

“By the next class meeting, enrollment had dropped from 30 to 7,” Johnson said.

But Johnson didn’t get discouraged because she’s always felt that she was born to teach.

“I loved teaching. There were days when I thought, ‘They pay me to do this?’” Johnson said, smiling. “The interaction between a teacher and students in a classroom can be extraordinarily rewarding.”

Johnson remained at the university for 40 years. In the 1990s, she was named chair of the Department of Languages and Literature (later dubbed Languages, Literature & Communication, and then English and Foreign Languages).

Now, more than 50 years after walking across the campus for the very first time, Johnson said she’s proud of the changes she helped make at Augusta University.

“As a student, I wasn’t trying to make a point, and I didn’t have a mission other than having the best and most engaging education that I could,” she said. “But, after I enrolled and did well, I think other African-Americans felt that they could succeed at the college. The diverse racial make-up of the college benefited us all, the college and the city of Augusta too.”

Welcoming African-American students in 1966

According to Dr. Lee Ann Caldwell, the director of the Center for the Study of Georgia History and a history professor at Augusta University, the first African-Americans who attended Augusta College began in the fall of 1966.

That year, there were only a handful of African-American freshman who enrolled in the college, including Eugene Hunt, who had been the sports editor for the Laney High School newspaper; Harold Canada, who was Hunt’s best friend at Augusta College; Thomas Hankerson, who had been on the Laney High School basketball team; and Judith Sullivan, who came from Immaculate Conception High School, Caldwell said.

“That same year, Norma Berry entered as a sophomore and Eunice Lott entered as a senior,” Caldwell stated. “The next year, in 1967 and 1968, over 20 African-American students entered the college.”

More than five decades later, Eugene Hunt still remembers the day he decided to apply at Augusta College.

“When I was at Laney High School, I played football and I had earned a football scholarship to Savannah State,” Hunt said. “But I used to read the newspaper and I remember when we played for the state championship in football, we got a tiny article on the back page that no one ever saw. But Augusta College was always on the front page with its basketball program with these nice, big photos. That’s what made me want to come to Augusta College.”

Not long after that revelation, Hunt said he met with his high school counselor who strongly encouraged him to apply to Augusta College.

“I had set it up that if Augusta College didn’t accept me, I was going to take the football scholarship and if that didn’t work out I was going to go to Paine College,” he said. “But Augusta College came through. It was my first choice and I was accepted in 1966. I majored in accounting and I graduated in 1971.”

Hunt believed there were about six African-American students who were the first to enroll at Augusta College in 1966.

One of the first African-American students at the college was his good friend, Harold Canada, who now lives in Orlando, Florida.

“The last time Harold was in town, we decided to drive around the campus and I couldn’t even navigate it,” Hunt said, laughing. “It’s very different from when we were there. It’s grown so much. But we had some good times on that campus.”

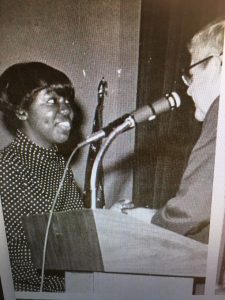

Hunt said the two friends enjoyed exploring the variety of activities and classes on campus, including everything from karate to swimming lessons.

“I remember the college had an indoor heated pool and I had never been exposed to a heated pool before,” Hunt said. “So Harold and I decided we were going to take swimming in the winter time because the pool was heated and we thought that it would be fun.”

The men quickly learned they had made a mistake.

“We froze to death,” Hunt said, laughing. “It was so cold.”

While a lot of the African-American students attending Augusta College would socialize with students at Paine College, Hunt said he developed lifelong friendships on both campuses.

“One of the things that I can recall is joining the fraternity, Alpha Phi Omega, at Augusta College,” Hunt said, adding that he didn’t stay in the fraternity his entire college career, but he enjoyed meeting the fraternity members. “Jerry Brigham, the former Augusta commissioner and Richmond County school board member, was in the fraternity. He and I established a relationship that has lasted decades.”

However, Hunt did acknowledge it took him a little while to get used to life at Augusta College.

“At the time, I was dating a woman, who’s now my wife, but she was in high school and I was at Augusta College,” Hunt said. “Well, I asked her on a date to come with me to Augusta College to a basketball game. When we got there, we were the only two black people in the gym.”

But Hunt said he never felt any major discrimination against him at Augusta College.

“We started the Black Student Union at Augusta College and the idea there was for the black students to sort of have a camaraderie and work through some issues,” Hunt said. “That way, we as a group could help improve things on campus.”

Looking back at his time at Augusta College, Hunt believes he received an excellent education that gave him a “leg up” on job opportunities.

“I was working with another fellow in New Jersey who was majoring in accounting,” Hunt said. “He started telling me the advantages of accounting. At that time, he said there wasn’t 100 black certified public accountants in the entire country. I don’t know how accurate that information was at the time, but it made me start thinking and I decided to major in accounting, too.”

Hunt said he is extremely proud of his degree from Augusta College.

“I worked hard for it,” Hunt said. “In fact, I used to drive an old car that was given to me by my brother-in-law. It was 1958 Cadillac. And I’m not exaggerating. I used to put 50 cents worth of gas in it every other day because that’s what I needed to get to Augusta College.”

The gas attendant would simply shake his head when he’d see Hunt driving up to the gas pump.

“The guy who pumped the gas for me, he knew I would come in there every other day. And one day he finally said, ‘You must have a nipple on that carburetor,’” Hunt said, laughing. “But I was grateful for that car because it was taking me up to college and bringing me back every day.”

A Circle of Friends at Augusta College

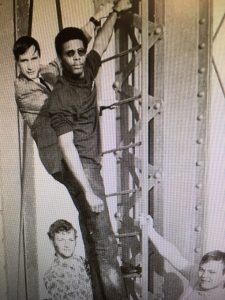

One of the main reasons Geri Sams, the procurement director for Augusta-Richmond County, decided to be one of the initial African-American students to attend Augusta College is because she was extremely impressed with then-Augusta College President George Christenberry.

“The president found a way to reach across racial lines and he had no tolerance for people who were not a part of the vision of a united school,” she said. “I remember one day, a group of African-American students decided to have a conversation about our purpose and what we wanted to do. We invited the president of the college. And I will never forget, we were all sitting in a line. And he insisted that we form a circle and he got in the middle of that circle and he started talking.”

That symbolic gesture had a major impact on Sams’ opinion of the president and the college.

“For me, that was very impressive. It proved to me that he was serious about listening to us,” Sams said. “And, out of that conversation, the Black Student Union was formed, which still exists at Augusta University today.”

While many African-Americans were still battling racism across the country in the late 1960s and early ’70s, Sams said she had a positive experience at Augusta College.

“We were young and energetic and we didn’t really realize that we were part of a movement or anything because that wasn’t our goal,” she said. “But there were real friendships that developed because of our presence on campus.”

It was a turning point for not only Augusta College, but the entire city, she said.

“Now, were there students looking at us cross eyed? Yes. Were there teachers who didn’t want us there? Of course,” she said. “But the greatest experience for me was there were more people who were ready for a change than the people who weren’t.”

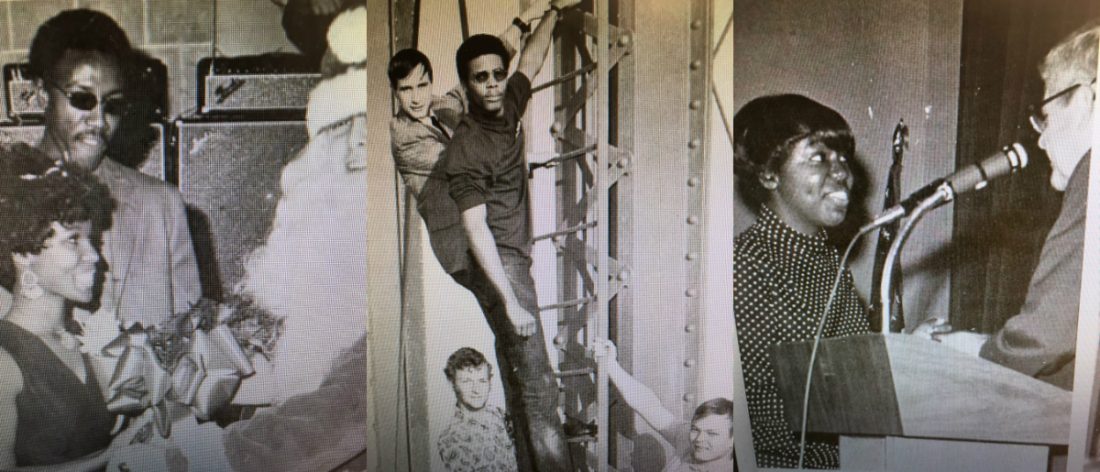

In fact, the college celebrated when Sylvia Grant, an African-American student from Jacksonville, Florida, was chosen as The Bell Ringer Beauty in 1968. Grant was also voted Miss Christmas Belle in 1969.

“She was a beautiful lady and the thing that made that so pivotal was the fact that there were so few African-Americans that were at Augusta College at that time,” Sams said. “But she won by a phenomenal number because of our presence at the college and the impact we were having on the campus.”

Sams also remembered when a group of African-American students requested that the college start a black history course on campus.

A few professors refused, but Dr. Edward Cashin, a beloved history professor at Augusta College from 1969 until 1996, stepped up to the plate and agreed to teach the class.

“Dr. Cashin said, ‘I’ve got the experience. I’ll do it,’ and he did,” Sams said. “Those things meant the world to us. So, for me, although attending Augusta College was a challenging experience, it was a very positive one. And there are many things in my life that I would do differently, but I would never erase my decision to attend Augusta College.”

Although Sams left Augusta College prior to graduating and finished her college career at Paine College, she will never forget her time at Augusta College.

“That small group of people who started at Augusta College broke through that glass ceiling. And I like to think of us as trailblazers,” she said. “And my courage, my willingness to change and improve things and my ability to reach across color lines, I have to think come from my experience at Augusta College.”

Those years at Augusta College changed her life, she said.

“When you talk about my development, my parents were the ones who raised me,” Sams said. “But Augusta College had a hand in developing me.”

Augusta University

Augusta University