Scientists from the Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University have been studying why bone and muscle decline with age. In a recently published paper, they found that drugs blocking the aryl hydrocarbon receptor, known as AhR, improved bone mass and prevented age-related declines in muscle function in older mice.

This research is built upon a program that has been in development for nearly 15 years. The paper was published in JCI Insight and is now in its third cycle of a Program Project Grant. This grant supports shared resources for various researchers, allowing a multidisciplinary and team-based approach to common research problems.

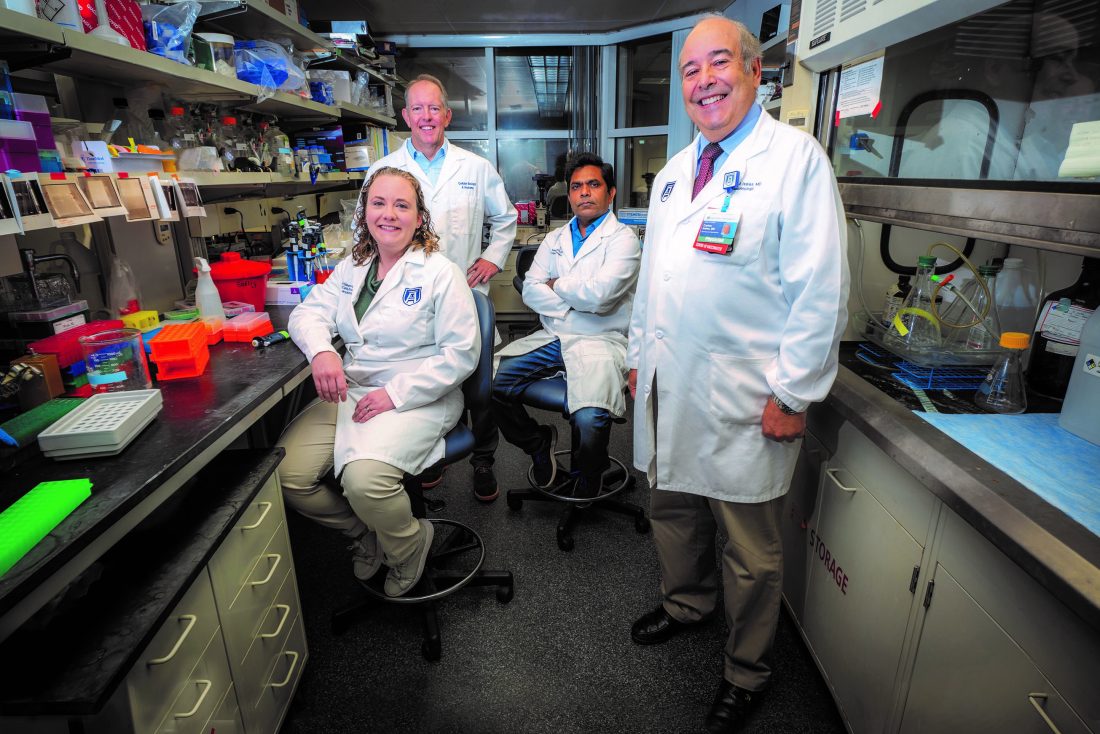

The team, which includes Meghan McGee-Lawrence, PhD, chair of MCG’s Department of Cellular Biology and Anatomy; Sadanand Fulzele, PhD, associate professor in the Department of Medicine and the Department of Neuroscience and Regenerative Medicine; and Mark Hamrick, PhD, a Regents’ Professor and bone biologist in MCG’s Department of Cellular Biology and Anatomy, found that activating AhR, especially with kynurenine, can lead to frailty, bone loss and muscle decline. AhR is a protein in your cells that reacts to environmental toxins and some metabolic byproducts.

“Our hope is that the discoveries we make during the research will provide new ideas on how to counteract or block the harmful effects of aging on our bones and muscle. We lose bone and muscle as we age, resulting in osteoporosis and sarcopenia. Being able to prevent this bone and muscle loss would let us remain healthier for longer.”

Carlos M. Isales, MD, the J. Harold Harrison, MD Distinguished University Chair in Healthy Aging and chief of the Division of Endocrinology

McGee-Lawrence said they are studying a pathway that changes with age. This pathway might drive bone and muscle loss in older adults.

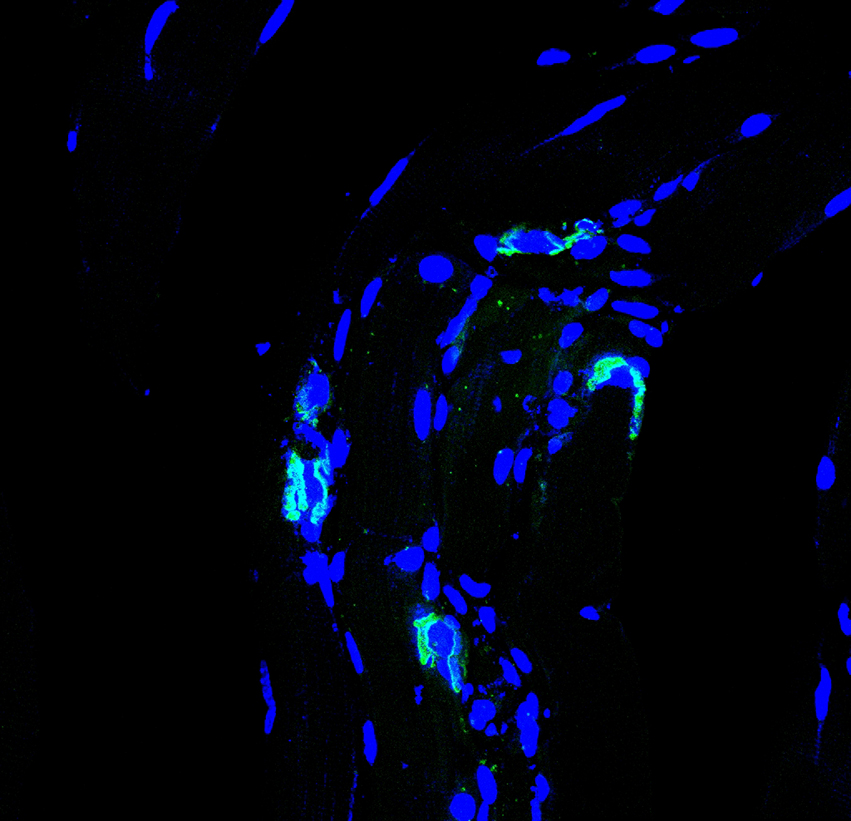

In their research, the team used drugs to inhibit AhR in aging mice, which improved cortical bone mass and enhanced muscle function. The improvements in muscle function were not caused by increases in muscle size, but rather by mechanisms that control muscle contraction. Inhibiting the AhR preserved neuromuscular junctions, which connect nerves and muscles, supporting movement and strength, especially in female animals during the study.

Carlos M. Isales, MD, the J. Harold Harrison, MD Distinguished University Chair in Healthy Aging and chief of the Division of Endocrinology, said his lab first focused on kynurenine, which increases with age and might mediate bone loss. He said they have been developing animal models where they can knock out the enzyme partly responsible for the conversion of tryptophan to kynurenine.

“Our hope is that the discoveries we make during the research will provide new ideas on how to counteract or block the harmful effects of aging on our bones and muscles,” Isales said. “We lose bone and muscle as we age, resulting in osteoporosis and sarcopenia. Being able to prevent this bone and muscle loss would let us remain healthier for longer.”

McGee-Lawrence’s lab studied AhR as a mediator of age-related decline and kynurenine’s effects on bone. She said age-related loss of bone and muscle is a big issue for many people worldwide, including in the United States. After age 65, many start to lose significant bone and muscle mass. This increases the risk of falls and fractures.

Fractures in older individuals don’t heal well, and, depending on the location, it can greatly affect mobility and quality of life. For example, one in five over 65 won’t survive a hip fracture, while the other four out of five will require some form of assisted care afterward.

A study from a few years ago showed that hospitalizations from age-related bone fractures are more common than those from strokes, breast cancer and heart attacks combined, according to McGee-Lawrence. She noted that the collaboration of gathering and then sharing the information is what makes team science crucial.

“When we work together, the science that we can do together is more impactful,” McGee-Lawrence said. “One of the great things about being part of this program project grant is that we all interact regularly. We have weekly meetings with our team of musculoskeletal scientists and also all of the other investigators who study mechanisms of aging on campus to talk about science and talk about where our research is leading us. With these types of collaborative studies, while it is a lot of work to coordinate the efforts across different labs, the payoff is tremendous.”

Hamrick, an internationally recognized muscle biologist, said his group’s research is centered on understanding the mechanisms underlying age-related muscle loss. He emphasized that elevated activation of the AhR, driven by dysregulated tryptophan metabolism, plays a critical role in accelerating muscle decline with aging. By targeting this pathway, his team aims to develop new strategies to preserve muscle health and function in older adults.

Fulzele, a bone and muscle biologist and director of endocrine research, said that AhR signaling alters lipid metabolism within muscle, a process closely linked to muscle weakness and frailty. He also noted that pharmacological inhibition of AhR not only prevented these detrimental metabolic effects but also supported the preservation of muscle function. These findings highlight how interventions aimed at blocking AhR activity could counteract age-related muscle decline and open new avenues for translational research focused on musculoskeletal health.

McGee-Lawrence said being able to share the information and receive feedback from the scientific community is a critical part of the collaborative process. She noted that the ability to coordinate these studies across different labs helped them produce a higher-impact paper.

“We saw these beneficial effects preventing age-related loss and muscle strength and bone mass in mice across several independent studies in each of our labs. We believe that at least for the bone-side of that equation, that benefit is coming from making the stem cells in the bone marrow that go on to become bone-forming cells proliferate faster,” McGee-Lawrence said. “The results that agree across independent studies give us the confidence that this is something that we should pursue further from a translational perspective.”

Discoveries at Augusta University are changing and improving the lives of people in Georgia and beyond. Your partnership and support are invaluable as we work to expand our impact.

Augusta University

Augusta University