AU Health, a pioneer in Patient- and Family-Centered Care, will hold its annual PFCC Conference this week.

It was the early 1990s when what was then the Medical College of Georgia began plans to create a children’s hospital in Augusta.

They consulted medical, financial and hospital administration experts, of course.

But they did something else when creating the Children’s Hospital of Georgia, and in the process cemented their role as pioneers in a new model of health care. They consulted patients and their families, and the model they helped create — patient- and family-centered care — has become the standard at top-rated hospitals around the world.

In patient- and family-centered care, or PFCC, collaborative partnerships between health care providers, patients and families are encouraged. Medical staff treat families as an extension of the patient and understand that families are critical partners in a patient’s care.

One patient and family journey

Eric Abbott had had a series of health problems since birth, including bronchitis, pneumonia and asthma. But in the fall of his kindergarten year, something different was happening: His face began swelling, and people began to notice and remark on it to his parents, Christine and Lance.

A few days after Thanksgiving that year, Eric woke up so bloated that he could no longer open his eyes. A trip to the ER at the Children’s Hospital of Georgia — the only pediatric emergency department in the region — revealed that blood and protein was spilling into his urine. The pediatric nephrology team was called in, and Eric was administered steroids. Doctors suspected nephrotic syndrome, a kidney disorder that causes the body to excrete too much protein into the urine.

Eric’s ordeal occurred just as the Children’s Hospital of Georgia, designed according to the principles of PFCC, officially opened in 1998. Christine and Eric attended the holiday tree lighting, and a local television reporter interviewed Christine about her family’s experience at the Children’s Hospital.

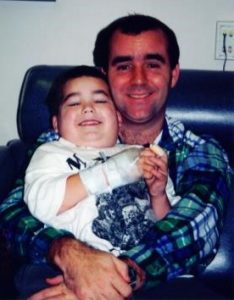

“Being able to be in Eric’s room 24/7 because he was so scared, especially in the beginning … was a safety net. It was that continuity of care, that extra set of eyes, that comfort,” Christine said.

Unfortunately, Eric’s health problems continued, and at age 5, he and his mom were in the nephrology clinic about every three days for medical assistance.

Designed for families

Each time Eric was admitted to the hospital, Christine stayed in his room with him around the clock. Patient rooms in the Children’s Hospital of Georgia were designed with family in mind. There are trundle beds for parents and guardians, because when a child is sick, it affects the whole family. Other unique amenities at the Children’s Hospital include access to a washer and dryer and a dedicated Child Life specialist, who can help explain medical situations to children and provide therapeutic play during their stay.

Doctors began to suspect that nephrotic syndrome was merely a symptom of a bigger illness. “We knew there was something wrong with him, but didn’t know what,” Christine said.

Christine, a self-described “control freak” began to keep track of her son’s drug regimen and his reaction to it on a laptop in his room. No one at the hospital batted an eye. Staff understood that recording data on their son helped the Abbotts become a part of his health care team, a key principle of PFCC.

“Patient- and Family-Centered Care made communication better, made the relationship better,” Christine said.

A kidney biopsy ultimately showed he had IgM nephropathy, an autoimmune disease that affects the kidney’s filters. Several immunosuppressant drugs were tried, but failed to control the illness.

Christine and Lance were given what she refers to as the “Grim Reaper speech.” Eric would likely need a kidney transplant at some point. Since Lance had the same blood type as his son, he began preparing to donate one of his kidneys.

A decade of damage in one year

In the meantime, a second biopsy found significant scarring of the kidneys.

“His body had done 10 years of damage in one year,” Christine said. “Doctors figured out that Eric has a missed-pattern protein. His body can’t find something, and it knows it’s wrong.”

Doctors began administering a high dose of Cyclosporin, an immunosuppressant drug, and, finally, Eric began stabilizing. Basically, he was going into medicated remission.

But the illness had ravaged his body to the point of stunting his growth, so that problem was addressed next.

By the time he was 17, Eric had gained weight and grown to 6 feet, 1 inch tall, but the Abbotts still expected Eric would need a kidney transplant. However, over the course of treatment, Eric’s kidneys had grown to adult size and the new tissue was healthy.

“The new tissue on these nice, big, honkin’ kidneys was disease-free,” said Christine. “It gave Eric a new lease on life.”

Paying it forward

At 21, Eric became a volunteer counselor at Camp Independence, a summer camp experience for children ages 8 to 18, living with kidney disease or related issues. As a child, Eric spent many weeks at Camp Independence before he turned 18 and went to college.

“There was a purpose to this,” Christine said. “I look at what Eric’s doing with these camps … Boys come back to him and say, ‘Look at the difference you’ve made in my life.’”

Eric and his family have also made a difference in the care provided at Children’s Hospital of Georgia. Eric served on the hospital’s Children’s Advisory Council until he graduated out, providing valuable input on everything from the food served in the cafeteria to the activities provided for patients and their families.

In addition, Christine served on the Family Advisory Council. Such councils empower patients and family members to be active participants in their care and to contribute to the development of care for future patients. That input often includes sitting on the design team to decide what the health care environment should look like. Patients and families also help bring in new ideas and solve problems that make caregiving more convenient and user-friendly.

“Patient- and Family-Centered Care is a really moving health care forward. Knowing that support is there, all of that coming together, was integral to my peace of mind,” Christine said.

Today, Eric lives and works in Atlanta, but he and his family played a significant role in crafting PFCC at Children’s Hospital.

Augusta University

Augusta University