Over the past several years, a growing number of women have decided it’s time to run for political office — more than ever before.

Ever since President Donald Trump took office in 2017, a record number of female lawmakers have won their seats and now serve in Congress.

And, in the the first time in history, voters saw a diverse group of female leaders pursuing the country’s highest office in 2020. However, only two white men remain in this year’s presidential race: Former Vice President Joe Biden and Trump.

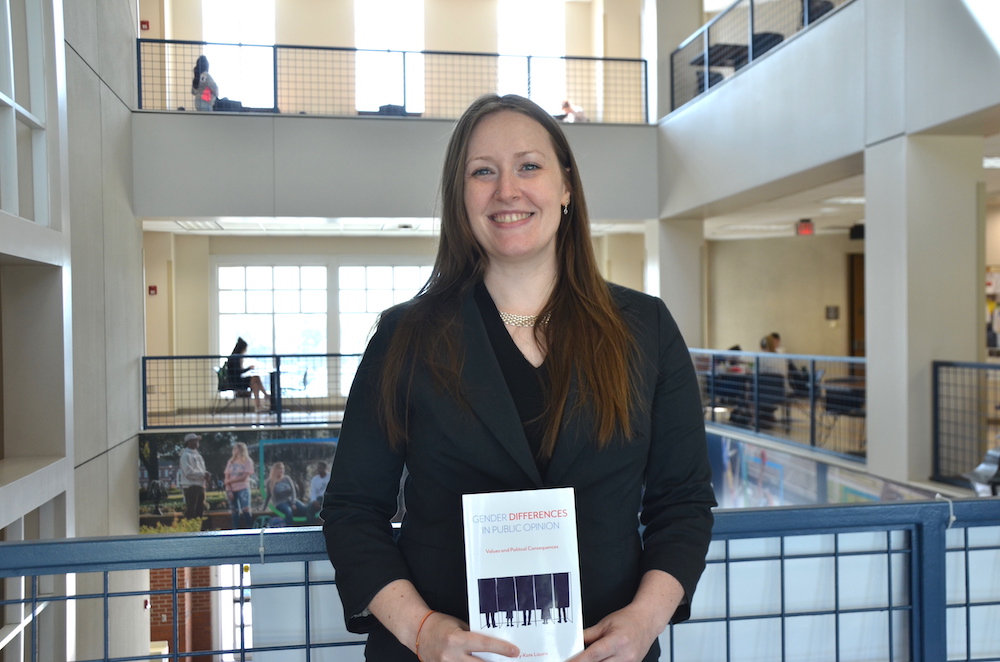

As more women continue to run for public office and activism increases among women, Dr. Mary-Kate Lizotte, an associate professor in the Department of Social Sciences at Augusta University, believes understanding gender differences on political issues has become critical.

In her recent book, Gender Differences in Public Opinion: Values and Political Consequences, Lizotte examines the gender differences in several policy areas such as equal rights, gun control, the death penalty and the environment, as well as social welfare issues. The result is an insightful study into how men and women vary in their policy positions and political attitudes.

“I’ve written several articles on gender differences in public opinion, focusing on one single issue area at a time. And I really wanted to think about what could possibly explain all these differences, such as the fact that women and men differ in their support for defense spending and military action,” Lizotte said. “They also differ on gun control, the death penalty policy, environment policy, social welfare policy and equal rights policy. And I thought looking at political values would be a great way to see if that helps us to understand why women differ from men on so many different issues.”

For her new book published by Temple University Press, Lizotte utilized nationally representative data, mainly from the American National Election Study, to study these gender gaps, the explanatory power of values and the political consequences of these differences.

“I was somewhat inspired by my dissertation that was focused on gender differences in support for war, so I thought it would be interesting to do a full book project on it,” Lizotte said, adding that she went to Providence College for her bachelor’s degree in political science and Stony Brook University in New York for her PhD in political psychology and American politics. “In fact, I had the idea for the book and started writing a proposal before I even got to Augusta University and started in the fall of 2016.”

Lizotte had previously met a representative from Temple University Press at the American Political Science Association’s Annual Meeting and Exhibition that year.

“They actually contacted me because of a topic that I was presenting there and they were interested in doing a book project with me, so I gave them the proposal and they were excited about it,” Lizotte said, adding she immediately began writing the first three chapters in early 2017. “It’s funny because I talk about the Women’s March in Washington, D.C., in 2017 in the book and I remember sitting in my apartment being bummed that I couldn’t participate in the march because I was working on the book that weekend. But then I thought, ‘Well, I’m doing my part to voice women’s issues and the positions that they have with this book.’”

In this year marking the 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage, Lizotte said political candidates need to identify with women voters and listen to their concerns.

In Gender Differences in Public Opinion, Lizotte explores how women tend to want a candidate who advocates for policies promoting social equality and the general population’s wellbeing. However, not all women view issues the same way.

“In the book, I look at differences between subgroups of women because I think it’s good, not just to focus on how the majority of women view certain issues or vote similarly to one another, but that there’s a lot of differences between subgroups of women,” Lizotte said. “In particular, race, income, education level and age are definitely factors. I didn’t look at religious traditions as a factor, but I’m sure that would also be an important dividing factor. So that was definitely interesting to kind of see the stark contrast between some of those subgroups of women.”

She continued, “But at the same time, to see that across all these different subgroups of women in comparison to men in the same subgroup, women still are more likely to support lots of different policies like pro-environmental policies and strong social safety net policies.”

Earlier this year, Lizotte wrote an opinion piece for MarketWatch discussing how Biden and Trump should take note of these influences when strategizing how to promote women’s turnout and garner women’s votes in November.

“Data on the presidential vote choice of men and women by demographic subgroup from 1980 through 2016 reveals that women are more likely than men in the same demographic subgroup to vote for the Democratic presidential candidate,” Lizotte wrote. “The overall gender gap between men and women who voted in the presidential race that election year during that period is only 6 percentage points. But within subgroups, the gap varies in size from 2 percentage points among African Americans and to 8 percentage points among those born prior to the boomer generation.”

The statistics regarding subgroups of voters is even more striking, Lizotte said.

“The biggest difference is the race gap: 99% of black women voted for the Democratic presidential candidate in those years compared to only 38% of white women,” Lizotte wrote. “It is still true that women, across the different subgroups, are more likely than men to vote for the Democratic presidential candidate.”

Lizotte said she’d love to see her book utilized in women’s studies classes around the country next semester so students could better understand gender in politics.

“I definitely worked to make it accessible at that level and, with an upper division class, it is something a class that focuses on public opinion or political behavior more broadly could really utilize,” she said. “In fact, I had a friend and colleague that I see at conferences utilize the book for the spring semester.”

Overall, Lizotte said she would like for readers of her book to better understand how gender impacts public opinion.

“At the end of the day, my book really pushes this idea that women think about and care about people close to them and people who aren’t necessarily close to them, just generally. They care about people,” Lizotte said. “Not all women and, obviously, not all the time, but, in general compared to men, women are more likely to think about what’s good for the wellbeing of other people. And I think that influences a lot of how women view the political parties, political issues and how they think about their vote choice.”

Augusta University

Augusta University