Nineteen years ago, when Trina Dennis’ first child was born, she noticed a white film covering her newborn daughter’s eyes. Doctors assured Dennis her daughter was perfectly healthy. The film would clear up. Nothing to worry about.

The doctors, however, were wrong.

Two weeks later, the film was still there. So, Dennis took her daughter to the pediatrician. Almost immediately the doctor recognized that there was a bigger problem, one he couldn’t handle himself. Though Dennis was living in Eatonton, Georgia, the pediatrician urged her to drive her daughter more than an hour to the Children’s Hospital of Georgia, where she could get the specialized care she obviously needed.

When Dennis arrived, doctors confirmed her worst fears: her daughter had been blind since birth. The diagnosis, congenital glaucoma, began a lifelong journey for Dennis and her daughter, Ravi Hudson.

It was also the beginning of an almost two-decades-long relationship with the Children’s Hospital of Georgia.

Congenital Glaucoma is an uncommon condition affecting approximately one in 10,000 babies.

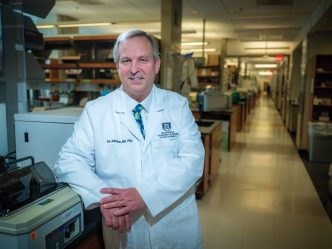

Dr. Stephanie Goei, director pediatric ophthalmology services and associate professor of ophthalmology and pediatrics at the Medical College of Georgia, sees about 6,000 patients a year and generally only diagnoses 3-5 cases of congenital glaucoma in that time.

The condition causes eye pressure to increase due to incorrect development of the drainage system in the eyes.

“The cornea is usually thicker due to swelling from this pressure,” Goei said. “The babies I usually see with congenital glaucoma also have large corneas. At birth, the cornea is generally 10mm, and with these babies it measures closer to 11-13mm.”

This eventually leads to damage of the optic nerve and loss of peripheral vision.

Congenital glaucoma results in a large, cloudy cornea due to increased pressure in the eye. This illustration shows the difference between a healthy eye and one with glaucoma.

So, Hudson also had multiple surgeries during the first five years of her life in effort to control the pressure and control the pain.

In many cases, the goal of these surgeries is to either increase fluid drainage from the eye or decrease fluid production within the eye. The ultimate objective of each surgery is the same, however; decreased eye pressure.

During this time, Hudson and her parents also underwent genetic testing at Children’s to determine if the glaucoma was hereditary.

“All the genetic tests came back showing that she didn’t get the trait from myself of her father,” Dennis said.

Though they did not receive answers about why Hudson had this condition, they continued in the journey treat the glaucoma, and each time they arrived at the hospital for a procedure, the Children’s Hospital was there like a faithful friend, helping Hudson however she needed.

“That’s the most amazing place I’ve ever been,” Dennis said.

She recalled a time last year when she brought Hudson in for an unrelated neurology appointment, an appointment made possible by the continuity of care offered by the Children’s Hospital that ensures any change in a patient’s condition can be quickly addressed. The pair ran into Miss Sheila, one of Hudson’s nurses.

“She remembered the day I rolled Ravi into the hospital in a stroller,” Dennis said. “We laughed and reminisced. She remembered Ravi as a baby and now she’s a young woman. When people remember things like that you know that the experience was awesome. They took care of us, and I don’t think we would have gotten that experience anywhere else. The care and passion from every staff member is unlike anywhere else.”

Due to scheduling conflicts stemming from living so far away, Hudson visited other hospitals for certain procedures, but she kept coming back to Children’s. It was home.

“We didn’t get the same care and attention other places that we got at the Children’s Hospital,” Dennis said. “There’s nothing else like it.”

Unfortunately, the surgeries weren’t successful in controlling the pressure in Hudson’s eyes. In fact, the pressure in Hudson’s left eye was so intense that it was causing nerve damage.

“High eye pressure can cause damage to the optic nerve,” Goei said. “The optic nerve is part of the brain, so it’s necessary to control the pressure so there isn’t continued damage.”

So, Dennis and Brooks began discussing the difficult decision of removing the eye and replacing it with a prosthesis.

“I was a new mom, and this was such a hard decision,” Dennis said. “Dr. Brooks assured me that if this was his daughter, this is what he would do. He was so genuine and helpful that it made the decision-making process easier. Dr. Brooks and his nurses were so helpful in answering questions. There was never a time that I didn’t get the help that I needed.”

So, when Hudson was six, they made the decision to remove her left eye to prevent further damage and a prosthetic was inserted.

Five years later, the pressure in Hudson’s right eye became uncontrollable, so it was also removed and replaced with a prosthetic.

Though she was too young to remember the first surgery, Hudson remembers the surgery for her second prosthetic.

“I don’t recall being afraid or even being in pain after the surgery,” she said. “I remember being excited. Before the surgery, I had one eye that was blue and one that was brown. It felt good to have both of my eyes the same color.”

Though obviously courageous, Dennis attributes a lot of her daughter’s bravery to how comfortable the Children’s Hospital made her feel.

“Dr. Brooks treated my daughter as though she was his own,” Dennis said. “He made us feel so comfortable. He would even carry her back for a procedure rather than wheel her back on a bed. When you’re in a situation like that and have someone giving you that care and love, what else can you ask for?”

While Brooks is no longer at Children’s, Hudson now sees Dr. Dilip Thomas, associate professor of ophthalmology at the Medical College of Georgia and director of the oculoplastics service at Augusta University Health. Thomas sees Hudson for regular check-ups and ensures that her prosthetics are functioning appropriately.

This seamless transition from one doctor to the next is another gift that Children’s was able to offer Hudson. This continuity of care means that there is never a lapse in the care or attention delivered to a patient.

Perhaps the biggest gift that the Children’s Hospital gave Hudson, though, was the opportunity to pursue a normal life, Dennis’ biggest goal for her daughter.

Dennis and Hudson worked together so that Hudson could live as independently as possible.

“I taught myself a lot of things, specifically life skills like cooking and cleaning,” Hudson said. “My mom and I found alternative ways to do things like putting Braille on our microwave.”

Hudson also took extra precautions to make sure she was successful in school.

“In elementary and middle school, my math teachers struggled with how to best teach me,” she said. “I think because math can be so visual at times. So, I had to figure out my own way that works for me.”

Ultimately, this team approach helped make Hudson’s childhood as conventional as possible.

“I always knew my vision was different because I started to learn braille instead of reading print, and I also walked with a cane,” Hudson said. “Other than that, growing up wasn’t any different for me. It was normal. I went to public school.”

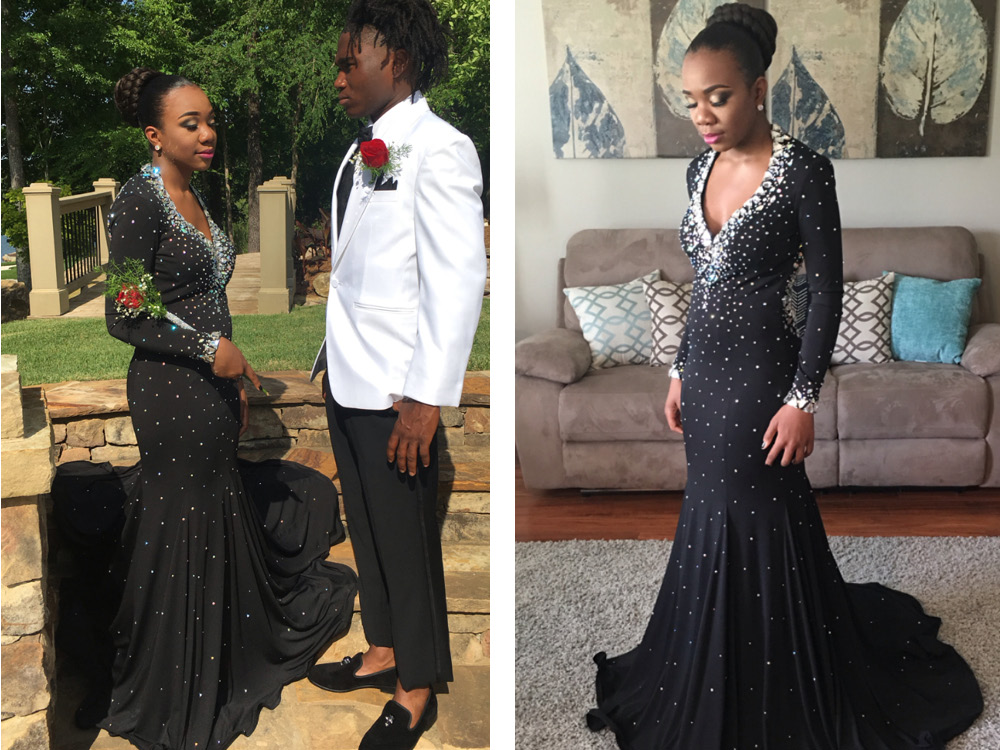

While in school Hudson was a cheerleader and a member of the beta club.

“She’s done everything that the average kid has done,” Dennis said. “Ravi’s had to do a lot of different things, but she knows she’s capable of doing anything she wants. She may have to do it differently, but she can do anything.”

Hudson is now in college, studying to be an English teacher. She has plans to pursue a career teaching visually impaired children and hopes to travel the world.

Throughout her life, nothing has held, or will hold, Hudson back, and Dennis credits the Children’s Hospital with much of that success.

“As a parent, you do whatever it takes so that your children have the best things in life,” she said. “The Children’s Hospital played a huge role in my daughter’s success and her ability to have a normal childhood. I know Ravi’s going to do some awesome things. I look forward to seeing what’s going to become of my little lady.”

Augusta University

Augusta University