In an apparent effort to help themselves, inflamed kidney cells produce one of the same inflammation-suppressing enzymes fetuses use to survive, researchers report.

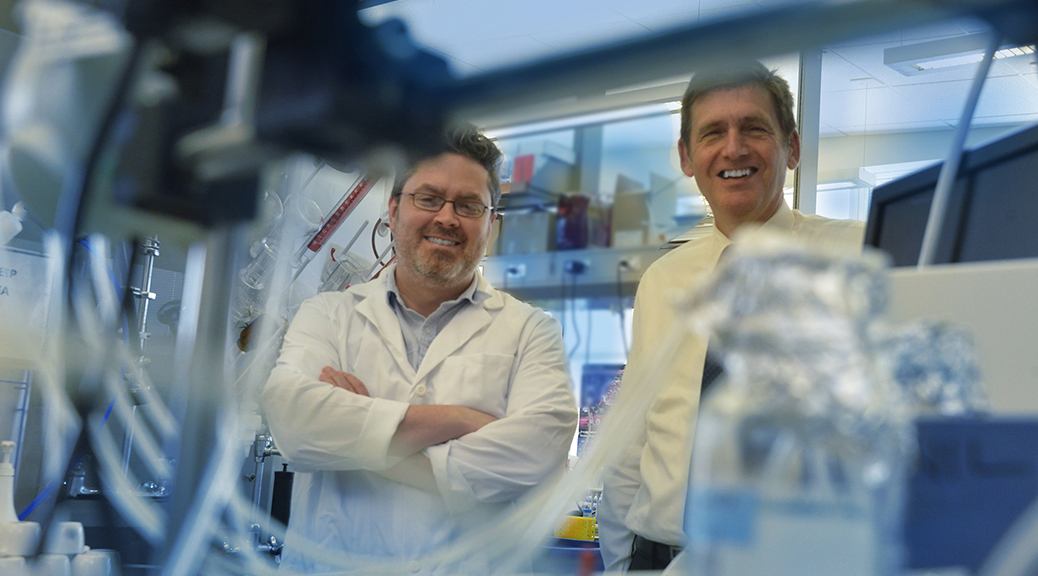

Inflammation is a major culprit in most kidney disease – from rare conditions, such as Goodpasture syndrome, where the immune system starts producing antibodies against kidney collagen to an infection with hepatitis C to the slow, persistent pounding of hypertension, said Dr. Tracy L. McGaha, immunologist in the Department of Medicine at the Medical College of Georgia at Georgia Regents University.

Prolonged inflammation can reduce or eliminate the kidneys’ ability to daily filter 150-180 liters of blood and enable resorption of most of that valuable volume, said Dr. Michael P. Madaio, nephrologist and MCG Medicine Department Chairman. Lost function means dialysis or a transplant.

In an animal model of inflammatory kidney disease, the researchers found kidney cells respond to potentially destructive inflammation by producing the enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, or IDO. IDO’s appearance sets in motion a chain of events that can eliminate the damaged protein produced during inflammation, allowing cells to better recover, said McGaha, corresponding author of the study featured on the cover of the Journal of Immunology.

They also found evidence of the same protective scenario in kidney tissue from humans with a variety of inflammation-related conditions.

When MCG researchers blocked IDO in an animal model then gave a fatal dose of an antibody to collagen found only in the kidney, it accelerated the already-rapid process whereby the normal structure of the kidney is replaced with dysfunctional scar tissue, suggesting IDO is part of the body’s natural protection against inflammation. “When the kidney cells couldn’t make IDO, the inflammation that was induced by the antibody caused those kidney cells to die,” McGaha said.

Even when they gave just enough antibody to induce mild inflammation in mice lacking IDO, it instead resulted in rapidly progressive and deadly kidney destruction. “If you inhibit the mechanism, the disease is worse,” McGaha said.

Once they saw IDO’s natural protective role in the kidney, they looked and found it was coming from the podocytes, a type of kidney cell with foot-like appendages that literally wrap around the capillaries of the filtering units, enabling the kidney to recirculate needed substances, such as sodium and protein, and excrete toxins in the urine that can cause damage. In humans and animal models alike, loss of podocytes, which have a limited ability to replicate, is directly linked to the kidneys’ lost ability to filter.

McGaha likens podocytes to gatekeepersn and when filtering fails, high levels of substances such as protein start showing up in the urine, which is why protein levels are one of the things measured in a urinalysis, Madaio said.

However, it wasn’t known that the kidney cells were providing another layer of protection by making IDO. The scenario goes something like this: podocytes make IDO, which consumes tryptophan, an amino acid that is essential for metabolism. Another enzyme, GCN2, is activated by the dearth of amino acids, initiating a stress response in the now-hungry kidney cells, which induces another natural cell process called autophagy.

While part of what autophagy does is enable the cell to consume itself, the goal is actually to enable the cell to survive and/or replicate. Autophagy slows production of the damaged protein made by the inflamed cells and eats up the damaged protein already made, McGaha said. If it’s early enough in the process, autophagy essentially clears out the damage, and the kidney cells recover. If autophagy goes on too long, because inflammation goes on too long, it triggers another natural cell process, called apoptosis, or cell suicide. It was already known that disrupting autophagy in mice leads to chronic, progressive kidney disease.

The researchers found that activation of the IDO-GCN2 pathway was essential to ensuring autophagy.

“The process of autophagy didn’t happen in the podocytes without those two,” McGaha said. “The podocytes went ahead and died.”

When they looked at kidney tissue from humans with a wide range of kidney disease, they also found levels of IDO and stress genes were way above baseline for healthy individuals, Madaio said, further indicating that the IDO-GCN2 pathway is functional in many types of kidney disease and identifying it as a potential new treatment target.

Early evidence suggests it may be a good one. When they gave DNA nanoparticles known to induce IDO, they found healthy mice kidneys produced IDO. When they gave mice a lethal dose of the collagen-injuring antibodies and the DNA nanoparticles at the same time, the IDO-GCN2 pathway was protective. The researchers also directly activated GCN2, and that worked as well, reinforcing the theory that it takes the enzyme pair to provide protection.

“What we are realizing is that most diseases have common pathways to either inflammation, fibrosis, or recovery,” said Madaio, a study coauthor. “What Dr. McGaha is doing is discovering those pathways or identifying new pathways in inflammation and protection.”

Next steps include learning more about how autophagy protects podocytes. Researchers also want to confirm their observation that activation of the IDO-GCN2 pathway is common in kidney inflammation.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Longtime MCG research colleagues, Drs. David Munn and Andrew Mellor, reported in 1998 that the fetus expresses IDO as a way to protect itself from being targeted by the mother’s immune response. Later studies found tumors use it as well. Mellor, an immunologist, developed the nanoparticles used in the new studies.

Augusta University

Augusta University