In the fall of 2021, women made up 64% of Augusta University’s 9,606 students spanning undergraduate, graduate, professional and post-professional studies. Included in that percentage, women make up 85.1% of nursing students, 81.1% of allied health students, 49.2% of medical students and 48.9% of dental students.

Behind those numbers is a rich history of women who helped pave the way, particularly within the Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University.

Women weren’t initially permitted into certain programs for a variety of reasons, including college leaders assuming women could not handle the rigors of the profession or were not dedicated to the career field. Though many of the first women at MCG were doubted at some point, each of these graduates helped pave the way for the women pursuing medical degrees today.

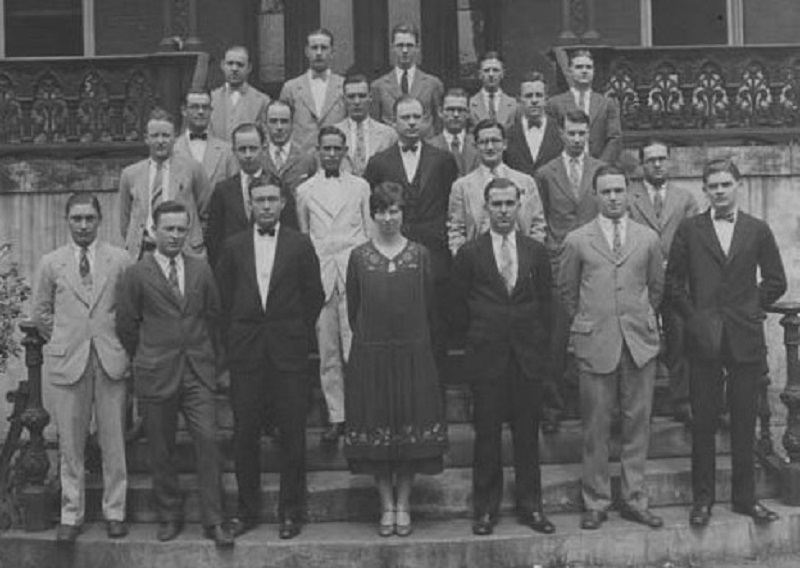

Dr. Loree Florence (1926)

Dr. Loree Florence is recognized as the first woman to graduate from the Medical College of Georgia’s School of Medicine, earning her degree in 1926.

When Florence was in grade school, there were only 10 grades to complete, and upon graduation, she went to Shorter College at the age of 15 to become a teacher. After graduating from Shorter, she taught for three years in a one-room schoolhouse in Wilkes County, Georgia, but it was during her time at Shorter that the seed of going into medicine was planted.

“While I was at Shorter, they had doctors there and they sort of somehow said I would do well in medicine. They sort of planted a seed,” Florence said in an interview in 1978. “Then I decided school teaching wasn’t for me.”

After a short stint working for the War Department in Washington, D.C., Florence “finally went over and took courses in chemistry, physics and zoology, and then I took one course in psychology and one in sociology and got a BS,” Florence said. “Then I went down to Augusta to see Dr. Lombard Kelly. So many wonderful doors have opened to me and I don’t see why. They were just opened and I walked in.”

While Florence found opportunity during her time at MCG, there was still pushback to a woman studying medicine.

“I knew some of the boys and had had classes with them the year before I went down there,” Florence said of her classmates. “I had been brought up in a male environment, you know. I had no sisters, and so the boys treated me like a sister and I did my work. I never tried to get out of anything. I thought, ‘Well, if the others can do it, I can do it, too.’ I didn’t work for grades. I worked because I loved it. It was just like doing something you like.”

Upon graduation, Florence interned at the Women’s Medical College in Philadelphia, and then worked at Smith College in Connecticut and Bellevue Hospital in New York. Later, she returned to her native Athens, Georgia, and opened a pediatric practice, and became the first woman to earn honors from Alpha Omega Alpha, a national medical honor society.

Dr. Emily Hammond Walker Wilson (1927)

Dr. Emily Hammond Walker Wilson was the second woman to graduate from MCG, following in Florence’s footsteps in 1927.

“I always wanted to go into medicine,” Wilson said during an interview in 1984. “We lived on a big plantation in those days with a lot of people living here … and no doctor anywhere close, and all the sick babies and all of the cut hands. My mother did the best she could. Having eight children of her own, she had a lot of practical experience about what to do with babies that were sick.”

Despite being only a year behind Florence, Wilson didn’t have much contact with her contemporary because of the practice of keeping the different classes very separate. Even though they didn’t have much contact, they still faced the same stigmas and resistance early on from certain groups.

“Everybody thought I had lost my mind. They just thought it was something I would probably do for a little while and give it up,” Wilson said. “Dr. Goodrich, who was then dean of the medical school at the time — he also happened to be our family physician — he said, ‘No way, we will not admit women.’ So that spurred me on.”

Once she had it in her mind to go to medical school, Wilson went to Goucher College in Maryland for pre-med, an experience she said was a shock because it was far different from the small hospital she had experience with at home.

After passing the first year, despite struggling in chemistry, Wilson heard about Florence being accepted to MCG in Augusta, so she made her way back to Augusta for her second year.

Wilson said her class started with two other women, but one left the program after the first year and the second the following year, leaving Wilson as the only woman in her class. Despite seeing the other two leave, she never wavered in her desire to become a doctor, in part because of her mother’s support.

“My mother fortunately was very much behind me,” she said.

After graduating from MCG, Wilson took an internship at the Central of Georgia Railroad Hospital in Savannah before accepting a position at Johns Hopkins Hospital, where she pursued a general practice.

In 1929, Wilson opened a practice in the southern portion of Anne Arundel County, Maryland. She was known as the first physician in Maryland to treat “tick fever,” or Lyme disease.

Wilson continued to open new doors for women during her career. She was first denied admitting privileges at the Anne Arundel Hospital, but eventually served as its chief of staff for two years, and also served as the first female president of the Anne Arundel County Medical Society.

Dr. Leila Daughtry Denmark (1928)

Dr. Leila Daughtry Denmark’s graduation from MCG in 1928 marked the third straight year that a woman graduated from the institution, and similarly to Wilson, she knew from an early age that she wanted to go into medicine.

“As a child, I was always interested in seeing things get well,” Denmark said in an interview in 1984. “I lived on a big farm down in Bullock County. The town of Portal was built on my father’s farm, but all of my life there was a world of animals on the farm, and there was always something that needed to be cared for. That was the most important thing in my life.”

Like her two predecessors, Denmark graduated as the only woman in her class, and like Florence, she started out in teaching before making her way to MCG.

While at Tift College, a professor introduced Denmark to dissecting frogs, which she found fun. Upon graduation from her undergraduate studies at Tift, Denmark spent one year teaching at Tift and two years teaching high school before she decided teaching wasn’t for her, and she sought admission to medical school.

Denmark’s pursuit of a medical degree began the day she walked into the admissions office at MCG and asked to be admitted. At the time, there were already 52 incoming first-year male students in the class, so it seemed impossible to add another student, but she persisted and was admitted. As is still the case in medical school, attrition caused the class to slim down to 36 by graduation.

Like her predecessors, Denmark found her male counterparts welcoming. “They treated me like a queen,” Denmark said. “I’ll never have a better time in my life than the four years that I was at the university.”

After graduation, Denmark was the first intern at the newly opened Henrietta Egleston Hospital for Children in 1928.

“I went over to see Dr. Hines Roberts at Henrietta Egleston Hospital about doing an internship,” Denmark said. “He told me I could have a job. I don’t know why he did that, but he did. I just walked in. He was the head of the hospital and he said, ‘Sure.’ There had never been a woman intern in this town, never.”

After two years at Egleston, she served a six-month internship at Philadelphia’s Children’s Hospital in 1930, and after the birth of her daughter, Mary Alice, Denmark opened her own private pediatric practice in her home. In addition to her private practice, she worked at a clinic at Grady Hospital and a charity clinic at Central Presbyterian Church.

In 1932 during a deadly epidemic of whooping cough in her community, Denmark began to study the disease. She worked with Eli Lily and Emory University in developing the first pertussis vaccine. Her research was published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, and she received the Fischer Award in 1935 for outstanding research in diagnosis, treatment and immunization of whooping cough.

During her career, Denmark published two books: Every Child Should Have a Chance (1971) and Dr. Denmark Said It: Advice for Mothers from America’s Most Experienced Pediatrician (2002).

In 2001, Denmark became known as the world’s oldest practicing pediatrician and continued to practice pediatrics until her eyesight was too weak at the age of 103.

Paving the way for others

Florence, Wilson and Denmark were followed closely by Dr. Mary Kate MacMillan Hires (1931), Dr. Katherine McMillan Hendry (1938), Dr. Katrina Rawls Hawkins (1940), Dr. Kathleen Byers-Lindsey (1943) and Dr. Phyllis Johnson O’Neal (1943).

Hawkins was chair of the Screven County Board of Health from 1965-87 and continued to work with the Screven County Health Department after retirement from her private practice. In addition to memberships in national, state and county medical societies, Hawkins was a charter fellow of the American Academy of Physicians and a charter diplomat of the American Board Family of Physicians.

Dr. Kathleen Byers-Lindsey completed a two-year residency in anesthesiology at New York’s Bellevue Hospital under Dr. Emery Rovenstine. She accepted an anesthesiologist position at Piedmont Hospital in Atlanta in 1947, becoming Atlanta’s first female anesthesiologist. In 1952, she became one of the first female anesthesiologists in the nation to be certified by the American Board of Anesthesiology.

O’Neal was one of three women to graduate in the MCG Class of 1943. After graduation, she completed her internship and residency at University Hospital. O’Neal and her husband, Dr. John B. O’Neal (MCG, Class of 1944), joined her father’s medical practice in Elberton, Georgia, marking the first time Elbert County had a female physician.

Look for upcoming stories about these MCG trailblazers on Jagwire.

Augusta University

Augusta University