Medical communities across this country are facing a harsh reality: people of color receive less care — and often lower-quality health care — than white Americans.

Whether an individual is facing cancer, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, HIV, asthma or COVID-19, the health outcomes of African American and Hispanic or Latinx patients are statistically worse than those of whites.

In truth, it’s a life and death situation. Over the next year, Jagwire will present a series of stories addressing racial and ethnic health care disparities and how Augusta University and AU Health are working to help.

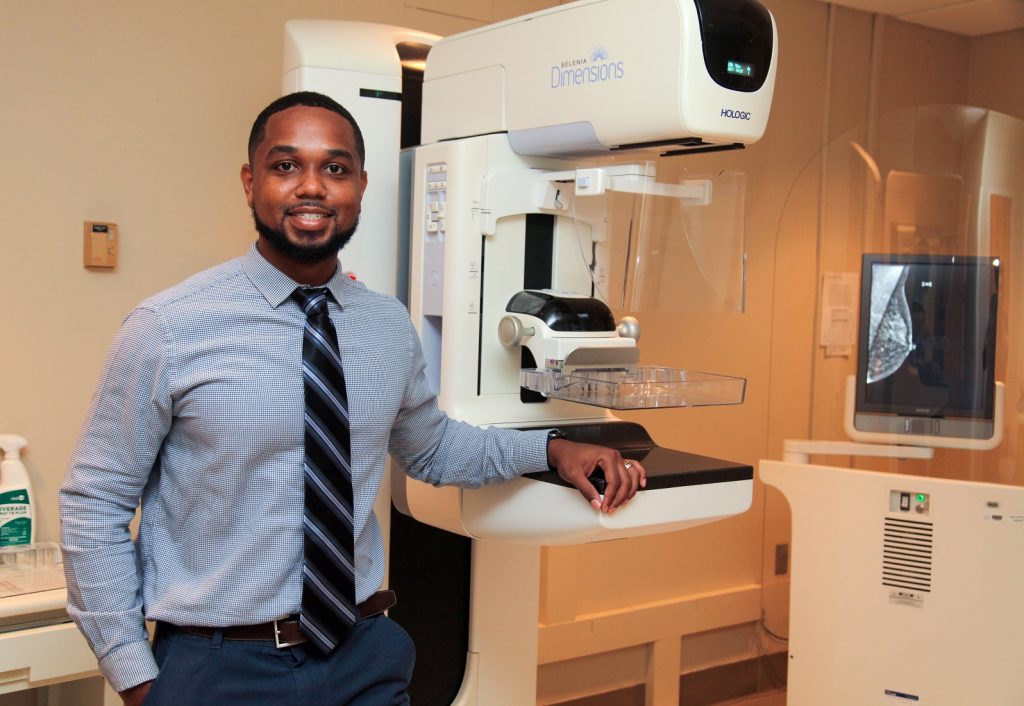

Without question, research has proven a person’s race and place of residence have a staggering impact on the quality of medical treatment a patient receives, said Dr. Justin Xavier Moore, an epidemiologist and assistant professor at the Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University.

“A lot of the research that I’ve done focuses on racial disparities in regard to looking at the intersection between race, place and health outcomes,” said Moore, adding his research mainly focuses on colorectal cancer, breast cancer, sepsis and, more recently, COVID-19. “So, with race, it includes self-reported racial identity, but also how structural racism and institutional racism may impact someone.

“And, when I say place, I’m talking about just how your zip code pretty much predicts your long-term health outcomes. Simply put, where you’re born and live has a huge role on health outcomes.”

Poor social determinants of health, such as the conditions where you live, learn and work, mixed with a low proportion of health care services in rural areas, can enable disease, he said.

Unfortunately, many health disparities in those living in underserved communities frequently begin at birth and are only compounded as the person gets older.

For example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports African American infants die at more than twice the rate of white infants. Black women are also two times more likely than white women to die of pregnancy-related causes.

African American and Hispanic women are 20% more likely to be diagnosed with advanced stage breast cancer and Black women have a 9% lower survival rate compared to whites, according to the American Cancer Society. Black men are also twice as likely to die from prostate cancer, as compared to white men.

In addition, the CDC recently reported that African Americans and Hispanics have been dying from COVID-19 at more than 2.5 times the rate of white people in this country.

To help address these health care disparities, Moore said the medical community must not only fully recognize these statistics, but also reach out to minority communities for answers to these tough questions.

“You must build a strong relationship with the community you are trying to serve,” Moore said. “It doesn’t happen overnight. I do a lot of work in, what we call, community-based participatory research or just community work in general, where I try to meet people where they are and be more inclusive of communities.

“I come to them to see what type of resources are needed to try to mitigate some of the burden of these diseases.”

Soon after joining the Medical College of Georgia in 2019, Moore became a volunteer with 100 Black Men of Augusta and began working with local churches and barbershops to develop relationships within underserved and minority communities throughout the area.

“These relationships show that there’s a presence,” Moore said, adding that Augusta University recently partnered with 100 Black Men of Augusta to host a virtual town hall on Feb. 12 to discuss the myths and facts surrounding the COVID-19 vaccine. “And it’s not just a presence that exists when you need something, like to do research, and then you’re gone. It has to be a presence that is more organic and builds trust.”

In the short time he has been in Augusta, Moore has already made great strides in connecting with underserved communities that are in desperate need of help.

“I’m also a person that comes from a very underprivileged, underserved background,” Moore said. “I grew up here in Georgia, in inner city Atlanta, in generational poverty. No one in my family had graduated college before. I was the oldest of 10 grandchildren and the oldest of five siblings. It was very, very humble beginnings and we had our challenges. I remember when I was 16 or 17 years old, we were homeless.”

Moore understands the uphill battles that many residents face living in the underserved areas of Augusta.

“In my life, there was housing insecurity, financial strain and I had so many family members die and fall early to chronic disease or cancer,” Moore said. “My dad died when I was nine years old from complications of diabetes and sepsis. So, that is why I studied chronic disease and research in sepsis.”

While some doctors might view such community outreach as going “outside of the goal or vision” of a medical college, Moore said he believes that’s simply not true.

“When you think about Augusta, Richmond County is 55% African American,” Moore said. “Here at MCG, we walk outside the door and the community in which we work is mostly Black. There’s so much that can be done and I think it just starts with reaching out. But it has to be active. It can’t be passive or reactive.”

Moore is a believer in living by example and he wants the underserved citizens of Augusta to know he truly cares.

“I guess, it just goes to the saying, you have to be the change that you want to see,” Moore said. “If you want something to be done, you can’t necessarily sit around and wait on someone else to do it. It has to begin with you.”

Dr. Phillip Coule, vice president and chief medical officer for Augusta University Health, has seen firsthand the devastating impact racial disparities in health care can have on people.

“We know that there are certainly deep and long-lasting, underlying health disparities in communities of color,” Coule said. “There’s higher rates of hypertension, heart disease, strokes and heart attacks that are certainly more prevalent in communities of color, particularly Black communities.”

There are several factors contributing to these disparities in health care, including lack of access to medical care as well as not being able to afford health insurance in some cases, Coule said.

“When it comes to paying bills and putting food on the table or choosing to have a doctor’s visit to get your hypertension diagnosed, then, unfortunately, some people make the choice of ignoring their health,” Coule said. “Then, we see these problems developing over time, from that underlying health issue that could have been treated decades earlier, to a more serious disease such as a heart attack, a stroke or kidney failure that can occur later in life.”

The key is to reach out and provide help to minorities in underserved communities before serious diseases can develop, he said.

“We’re working with the American Heart Association to help provide education as well as just raising awareness about hypertension and the impact that can have on your health,” Coule said. “One of the other big programs that we’re supporting, in partnership with the American Heart Association, is dealing with issues of healthy food access, because the area surrounding Augusta University is a food desert.”

“Food deserts” are geographic areas where access to affordable, healthy food options such as fresh fruits and vegetables, is limited or nonexistent because grocery stores are too far away.

“If you don’t have transportation and the only place that you have to buy food is a convenience store, then it turns out that your diet tends to be poorer,” Coule said. “So, organizations like the American Heart Association and Augusta University are working together to help reduce that food desert phenomenon through very tangible efforts like the farmer’s market, where we’re partnering with local growers to help bring in fresh produce and make that available within the community.”

Medical colleges around the country must also prepare future doctors and health care workers to be cognitive of the longstanding inequities that pervade the health care system and provide short-term and long-term solutions to reduce these disparities, Coule said.

Some medical students may not have the life experience to fully understand the economic constraints of having to travel long distances to seek health care or not being able to afford medical insurance, he explained.

“I work in the emergency department, and any time I go to prescribe a medication and the best medication might be more expensive, I always tell the patient, ‘This is what I think the best option is, but there are cheaper options that we can use,’” Coule said. “That gives the patient choices. If you just write the prescription and the person doesn’t know it’s going to be expensive, you’re not helping that person because, chances are, when they find out the price, they likely won’t get it filled. Patients need to know there are lower-cost options.”

Diversifying those serving within the health care system, particularly doctors, will also positively impact the medical community’s relationship with minority communities, Coule said.

While African Americans make up 13 percent of the country’s population, only 5 percent of physicians are Black. That lack of diversity can impact a patient’s views of the medical community.

“I can deliver a message all day long and I would like to think that I’m a trusted source and the message will be said and delivered in a way that resonates with everyone, but, the truth is, we all relate better to some people more than others,” Coule said. “Sometimes the message may need to be delivered by somebody who looks or sounds like the patient. That’s why it’s so important for us to have diversity in our workforce.”

Dr. David Hess, dean of the Medical College of Georgia, understands the importance of a diverse institution and the impact such diversity can have on the future health of citizens across the state.

“Currently, Georgia’s population is about 32% African American and we would love to have 25% to 30% African American students at MCG to mirror the demographics of the state,” Hess said. “One of our major emphases and thrusts is to increase underrepresented minority scholarships here at MCG, and the MCG Foundation has been a big help in funding those scholarships.”

Overall, the Medical College of Georgia has a “holistic admissions process” that assesses an applicant’s unique experiences alongside traditional measures of academic achievement, Hess said.

“No one thing ever gets a student into MCG,” Hess said. “But factors that we take into consideration are African American and Hispanic students and also students from south Georgia, because we don’t have as many students from south Georgia and that’s where the physician shortage is the most severe.”

In 2017, MCG began following the holistic review recommendations developed by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) as well as internal guidelines developed by the admissions committee made up of 20 dedicated faculty members and students, said Dr. Kelli Braun, associate dean of admissions for the Medical College of Georgia.

“We look at the context of the individual, so it’s not solely metric driven or based on a person’s GPA or their Medical College Admission Test (MCAT) score,” Braun said. “While we follow national benchmarks for assessing the academic readiness of our applicants, equally as important are an individual’s experiences and attributes in selecting the next generation of future physicians.

“Our mission, as the Medical College of Georgia, is to give back to the health care of the state. And, in doing that, we try to build a class that is much more reflective of our state in general.”

Approximately 3,000 applicants apply to MCG each year and those applications are reviewed by the MCG admissions committee, which is composed of faculty, students and representatives from our regional campuses, Braun said.

“We meet every single week from August through February and we pore over all of these applications,” Braun said. “And what we’re looking for is, number one, do these students fit with the mission of our school? Are they committed to the health care of Georgia? Secondly, how will that individual contribute to the diversity of our class? Are they from a specific area? Do they have unique life experiences? What will they contribute to the class?

“Because we know that if you are in a diverse class, you do better and you learn better, and you become a much more culturally competent physician.”

The majority of the applications to MCG come from students within the state of Georgia, Braun said.

“We are the state’s only public medical school and 95% of our students have to come from in-state,” she explained, adding that MCG has made it a priority to include students from across Georgia. “We’re geographically diverse within the state. We have mountainous areas, coastal areas, rural areas, and urban areas. So, part of building that diversity of the class is looking for students from all of these regions, because we know we have health care inequities within the state.”

In fact, the Medical College of Georgia has developed a 3+ Primary Care Pathway that will help place doctors where they are needed most in the state. This pathway shortens the traditional MD curriculum to three years instead of four and will provide free tuition or student loan forgiveness to students who commit to a primary care residency and agree to serve in an underserved area for three years.

“By primary care, we mean doctors practicing family medicine, internal medicine, pediatrics, OB-GYN, emergency medicine and general surgery. So, it’s very broad, but we need more of those doctors in underserved Georgia,” Hess said, adding that a large percentage of the population in these underserved areas are minorities. “The idea of 3+ is we’ll get you through medical school in three years and you can start a primary care residency in Georgia. In your fourth year, you’re really graduating, so you’re saving a year, and we’ll pay your tuition for three years if you practice in underserved Georgia for three years. And underserved Georgia is, unfortunately, most of Georgia.

“Georgia ranks about 40th in the country in physicians per capita, and it’s really worse than that because most parts of Atlanta have physicians, but the rest of the state doesn’t.”

If a student grew up in an underserved area of Georgia, that can often be an indicator as to whether the student would consider returning to that region after graduating, Braun said.

“If you’re trying to predict who will go to those underserved areas and serve those communities, one of the most important factors is, did they come from that area?” Braun said. “Students are much more likely to go back and be a part of their home communities.

“Therefore, diversity, for us, means lots of things. Obviously, racial and ethnic minorities within our state are incredibly important as are people from under-resourced areas. And I think our job as an admissions committee is to make the process as fair and equitable across the board as we can.”

Ever since the holistic review approach for admission was promoted back in 2017, MCG has become a more diverse campus, Braun said.

“Prior to 2017, we were a less diverse campus,” Braun said. “Back then, the racial diversity of our class was typically around 8% for African Americans and Hispanics. Since 2017 and the introduction of holistic review, we now range anywhere from 16% to 26% African American and Hispanic students in each entering class at MCG.”

Fortunately, medical student enrollment has actually increased over the past year at MCG, Hess said.

“We’re going to have 20 more students this coming year, going from 240 to 260,” Hess said. “We have a record number of applications this year, as do all the medical schools in the country, because medicine is more popular than it ever was. We call it the ‘Fauci’ effect.’”

Dr. Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, has become a household name for his work on the White House coronavirus response team over the past year.

“There’s a silver lining in every cloud, even the pandemic, and one positive is the increased interest in medicine, but we also want to get more underrepresented minorities into medicine,” Hess said. “And getting underrepresented faculty is even harder. There’s a huge shortage of African American faculty in medical schools throughout the country.

“We would like our faculty to look more like the population of Georgia. That’s an aspiration, but we’ve got a long way to go.”

While the Medical College of Georgia attracts a vast number of international faculty members to the institution, that is not the case when it comes to African Americans and Hispanics, Hess said.

“It will take years to change that, but if we have more medical students who are African American and we have more African Americans doing their residencies here, then we’ll have the opportunity to proactively recruit them to become faculty members,” Hess said. “But, one of the first things we needed to do is make life better for the African American faculty we have here now.”

There is a “heightened awareness” at MCG to listen and understand some of the challenges Black and Hispanic students and faculty members are facing at the institution, he said.

“A lot of it was about listening to how they felt like they were not treated equally,” Hess said. “And I agree, when you hear the stories, it’s true. When an African American faculty member goes down and sees an African American patient in the emergency room, they notice that they’re treated differently. So, we’re working on that, but that takes a lot of education.”

One way to improve recruiting more minority faculty members is to incorporate a diverse search committee, Hess said.

“With a diverse search committee, we get a diverse candidate pool and it’s not just racially diverse, it also has to do with gender. There’s a shortage of women in medicine,” Hess said. “So, we’ve also made an effort to have more women leaders here at MCG. In fact, we just recruited a new chair of surgery who is a woman. But we still need more diverse chairs. We need more Hispanic and Black chairs.

“But you can’t snap your fingers and immediately change that. We’ve got a long way to go and we’re not going to do it overnight, but we’ve made a start.”

It is vitally important to attract more students of color into a wide range of positions within the health care field, said Dr. Tiffany Townsend, the chief diversity officer for Augusta University.

“I want our students to understand that if they’re interested in addressing this health disparity that we’re seeing, and it’s very glaring now, that there are several different avenues that they can take in order to make a difference,” Townsend said. “They could be a medical doctor, a biomedical researcher, or even a behavioral health researcher. They could also be a social worker or a case manager. All of these different aspects of health are so important in making sure that we’re addressing these disparities.”

For 51 years, the Medical College of Georgia has offered a pre-college Student Educational Enrichment Program (SEEP) for current high school juniors and seniors enrolled in either the Richmond County or Columbia County school districts, as well as a college-level SEEP. Pre-college SEEP expanded to Savannah in 2012, and is open to high school juniors and seniors enrolled in the Chatham County School District.

The pre-college SEEP Augusta is a seven-week program, while SEEP Savannah is a six-week program, and there is no cost for students to participate. SEEP prepares students for a future career in the health professions through an extensive academic course.

“The whole idea of that program is that you try to connect with students very, very early in the pipeline,” Townsend said. “These students are exposed to some of the basics, and provided strategies and skills to make them successful in college.”

SEEP College is a seven-week summer program with two levels. Each track helps prepare students for a future career in the health sciences, with an emphasis on medicine. The academic program includes an advanced biomedical science course; an upper-level critical thinking and clinical-based, problem-solving skills development component; and preprofessional and personal development.

Participants at these levels receive college credit for biomedical science courses offered in the program and there is also no cost to participate in these programs.

Linda James, assistant dean for Student Diversity and Inclusion at the Medical College of Georgia, said 70% of the SEEP alumni, which is more than 1,000 students, have matriculated into health professions programs, with about 50% of these entering medical schools throughout the country.

Townsend has also recently applied for a grant to fund another early pipeline program that will hopefully encourage more underrepresented students into the science fields, particularly the behavioral health sciences.

“The whole idea is that we want to get students very early in their college career, right when they walk in the door, to consider behavioral health and behavioral health research as a viable option,” she said. “We also want to train doctors who are already in place to make sure that they’re listening to the voices of marginalized communities, such as people of color, or members of other communities who may not necessarily seek the care of a doctor because of the very sensitive and often negative relationship that some communities have had with the medical establishment.

“Health care providers have to understand that history, and appreciate the reason for that hesitancy. We want to train our doctors to have cultural sensitivity.”

Getting future doctors and current doctors to fully recognize the systemic racism in health care isn’t an easy task, but it’s necessary, Townsend said.

“We’re seeing that there are people of color coming in with symptoms that are not being treated and not taken seriously. I’ve had personal experiences with it,” Townsend said. “And folks will say, ‘Well, it’s about access to health care.’ No, it’s not just about access. For example, I have personally witnessed disparities in the health care of my family. Despite having a college degree and good health insurance, several members of my family have reported symptoms that were repeatedly minimized until it reached a later stage in the progression of the illness.”

Then, suddenly, the medical staff seemed surprised by the diagnosis, even though prior symptoms and complaints had been reported, Townsend said.

“There were complaints all along the way that weren’t taken seriously and weren’t tested,” she said. “Therefore, I take the structural inequities that are being played out in our health care system, personally. And a lot of it has to do with cultural differences.

“Results of a 2002 meta-analysis published by the Institute of Medicine indicated that a major factor contributing to health disparities in our health care system is that some health care providers don’t understand differences in symptom presentation among certain communities, particularly communities of color.”

That’s why cultural sensitivity training is so valuable. The truth is, we all have biases and health care providers are no different, Townsend said.

“However, we’re often not aware them. What we have to do is have spaces where it’s OK for us to examine those biases,” she said. “We all need safe spaces to really have a mirror held up so we can understand our own hang-ups and triggers. The goal is to help people be more mindful of their biases so that it doesn’t impact their decision-making.”

Another key component to culturally responsive care is integrated health care, Townsend said.

“Having health care providers see their patients as a part of the team, while also getting different medical perspectives, not just from other doctors, but also from different disciplines is vital,” Townsend said. “It helps to give a fuller picture of the patient and having a more complete picture of patients will go a long way in helping to ensure more effective treatment for all.”

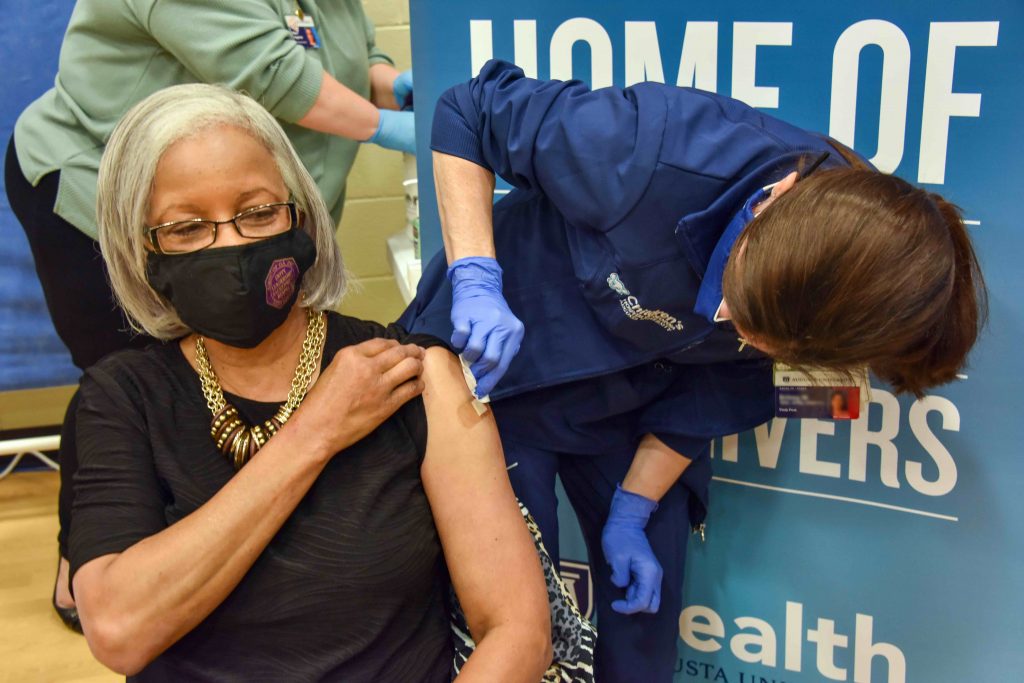

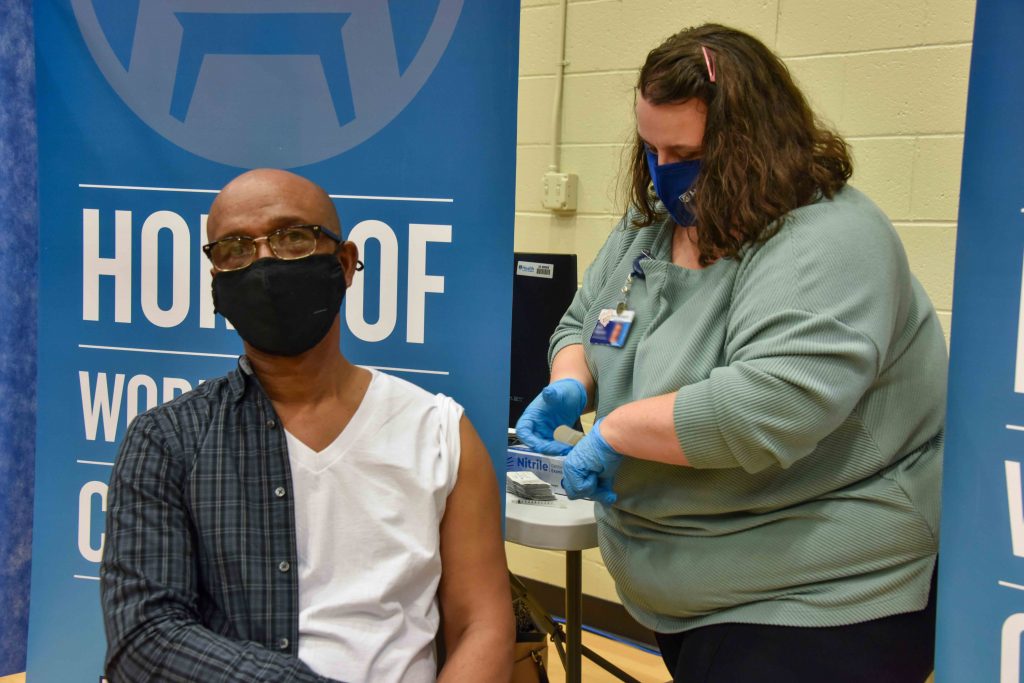

The COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately affected people of color, particularly Black Americans. Jagwire will look at the disparities and discuss the work Augusta University and AU Health are doing to share accurate information about the virus and provide access to the vaccine for Augusta’s underserved community.