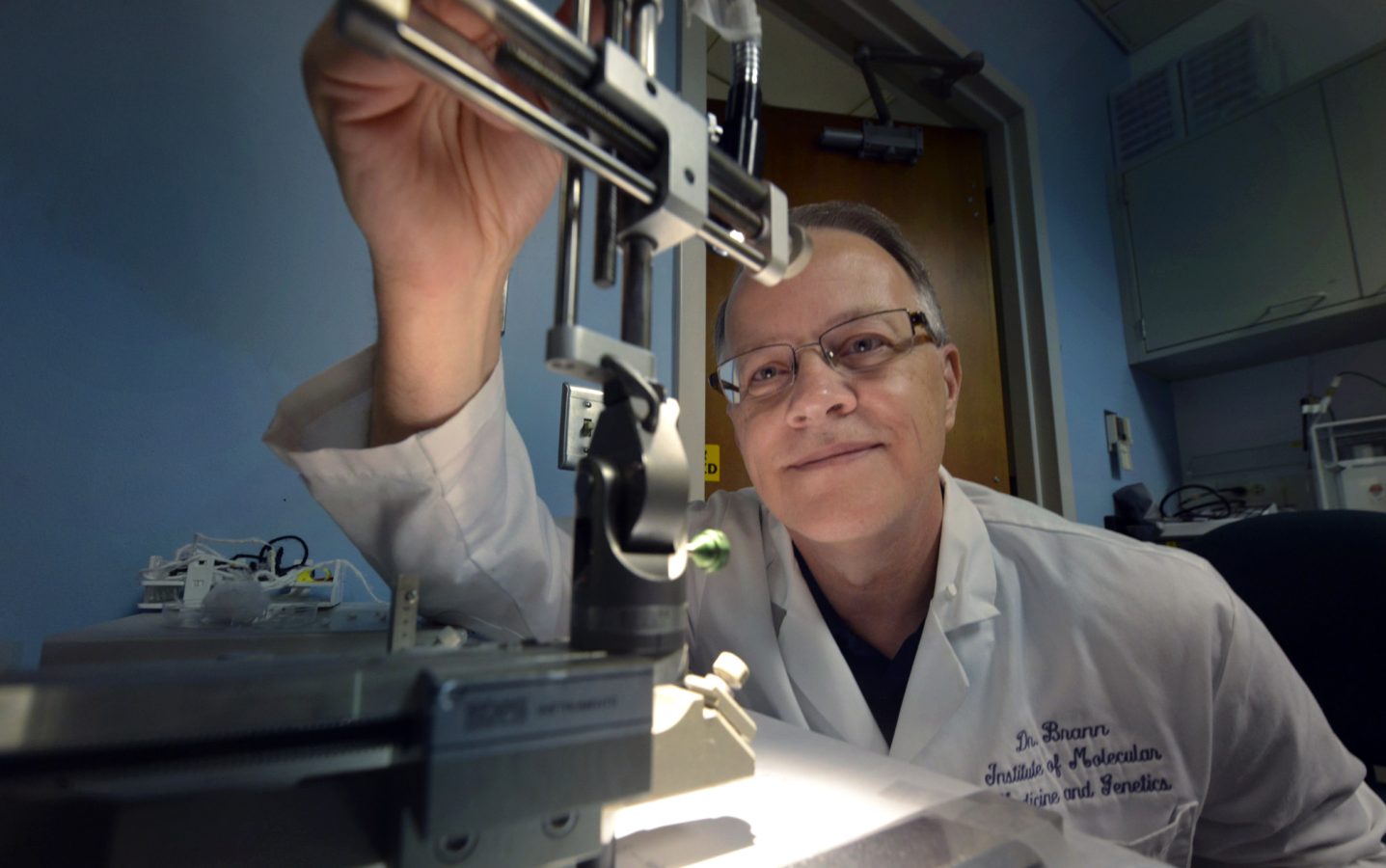

Dr. Darrell Brann, Regents’ Professor and the Virendra B. Mahesh Distinguished Chair in Neuroscience of the Department of Neuroscience and Regenerative Medicine at the Medical College of Georgia, has always known the value of mentoring.

After all, Brann was named the inaugural Virendra B. Mahesh Distinguished Chair in Neuroscience in 2017 after one of his own mentors.

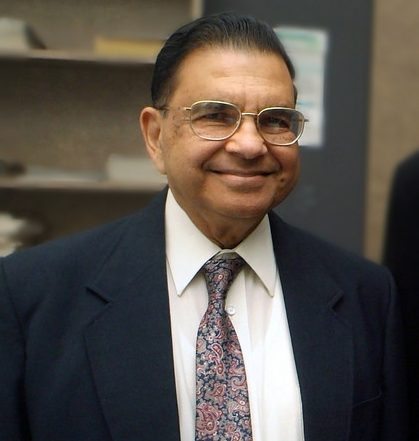

The late Dr. Virendra Mahesh was a former Regents’ Professor and chair of the Department of Endocrinology at MCG. He was a renowned endocrinologist, whose research on steroid hormones led to a greater understanding of the role in physiology and disease, and to the development of groundbreaking treatments for infertility.

After joining MCG as a member of the Department of Endocrinology faculty in 1959, Mahesh conducted research that determined progesterone combined with estrogen in a birth control pill could produce contraceptive impact with much lower risks of blood clots, resulting in benefits for millions of women worldwide.

Unfortunately, Mahesh passed away last year, but his mentoring helped inspire Brann at MCG.

Brann received his PhD in endocrinology with distinction in 1990 from MCG, where he also completed a postdoctoral fellowship in neuroendocrinology.

Brann’s research over the years has contributed significantly to enhancing understanding of 17b-estradiol (estrogen) signaling mechanisms and actions in the brain, including its anti-oxidative stress, anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective actions in the brain.

In addition, Brann’s recent work has focused on elucidating the role of “brain-derived” estrogen in neural plasticity and neuronal survival, as well as in its control of cognitive function.

Despite all of his success, Brann has never forgotten the leadership and guidance that Mahesh provided him as a student.

Throughout his career, being a mentor to students has played an important role for Brann.

“Working with the graduate students and supporting them is one of the most rewarding aspects of my career so far,” Brann said. “Seeing young people that are going to carry on the future for us and trying to help them set up their careers is what it is all about.”

Therefore, it comes as no surprise to his students and colleagues that Brann was selected as this year’s Distinguished Faculty Award winner.

“To me, this is a great honor because this award is voted on and selected by our peers and I had some students who also joined the nomination with other faculty, so that’s very rewarding,” Brann said. “Personally, I think being a leader is simply serving others, so I’m just very happy that people believed in me enough to give me that opportunity to serve others.”

Helping the younger generation succeed

While Brann has received many awards and honors in his career, including the Distinguished Alumni Award from MCG in 2001 and the Augusta University Research Institute Lifetime Achievement Award in Research in 2014, he has also strongly supported biomedical PhD graduate students at MCG through several endowed scholarships and by serving on the Advisory Committee of more than 59 graduate students.

In fact, one of his former students, Dr. Krishnan Dhandapani, has received the Distinguished Research Award this year from Augusta University. In addition, Dhandapani has received the Distinguished Alumni Award from the university, Brann said.

“I’ve been very fortunate to have great students that come through my lab,” Brann said. “I think our main goal at the graduate school level is we want to help students develop their independent thinking skills and critical thinking. That’s very much important.”

One of the best ways to accomplish that goal is to make your lectures interactive, Brann said.

“I think that’s key,” he said. “Students start out at a certain point and a couple of years later, you’ll see how much they have really grown and developed those independent thinking skills. But you have to challenge them and always set the bar high for them to meet.”

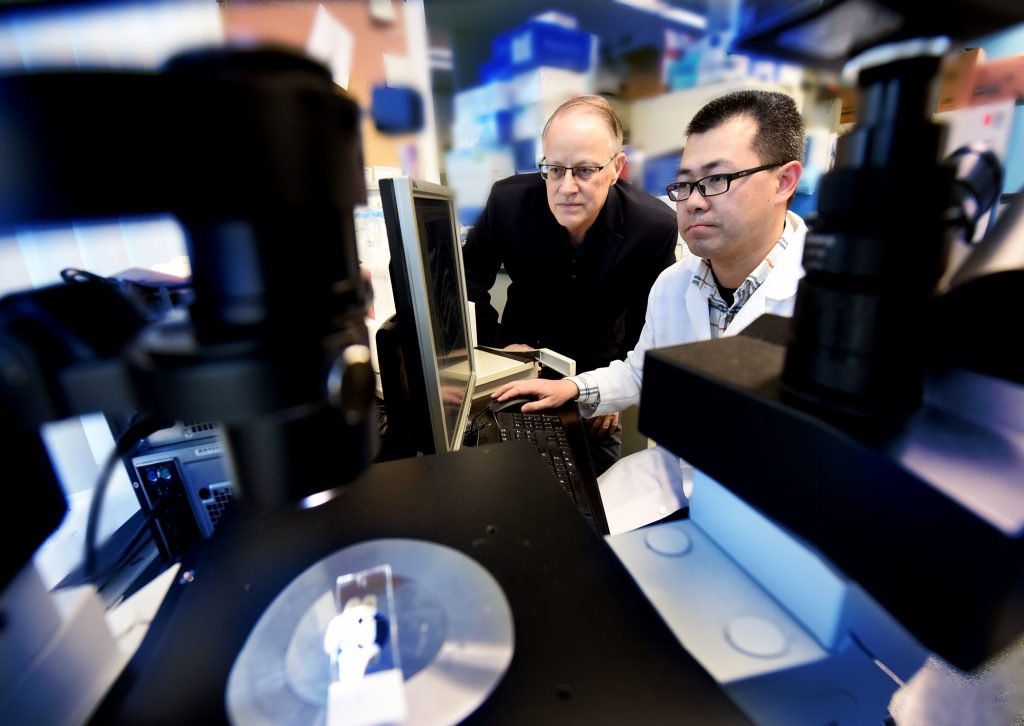

Dhandapani, now a professor and neuroscientist in the MCG Department of Neurosurgery, is one of those students who excelled in Brann’s lab.

Trying to prevent life-threatening strokes

Over the past several years, Dhandapani has teamed up with Dr. David Hess, stroke specialist and dean of MCG, to study if successive bouts of compression and relaxation of a limb with a blood pressure-like cuff prepares the brain to better weather the lack of oxygen that occurs in stroke.

The National Institutes of Health is funding the comparison of potential new stroke therapies in an initiative called the Stroke Preclinical Assessment Network, or SPAN.

Stroke is a leading cause of death and long-term disability in the United States.

Dhandapni’s research into this area was one of the main reasons he received the Distinguished Researcher Award this year.

“With my own research, I direct neurosurgical research in the Department of Neurosurgery and my research is mostly focused on traumatic brain injuries and hemorrhagic strokes, which are both major neurological problems,” Dhandapani said. “In the case of hemorrhagic stroke, which is one of the papers I published at the very end of 2018, but it carried into 2019, is something called intracerebral hemorrhage.”

Intracerebral hemorrhage, or ICH, is caused by bleeding within the brain tissue itself and it is a life-threatening type of stroke, he explained.

“These are patients that typically have chronic hypertension or high blood pressure for many years, or they can have something called cerebral amyloid angiopathy, which is a buildup of amyloid in the blood vessels,” Dhandapani said. “What ends up happening over years, just due to too much pressure on the blood vessels, eventually one of these vessels in the brain will actually rupture and start hemorrhaging into the brain, so it’s a major problem.”

There is generally a mortality rate of about 50% with ICH, he said.

“When I first joined MCG, I had not really been familiar with intracerebral hemorrhages, but I learned a lot from Dr. David Hess, the dean of the medical school, because he’s a stroke neurologist,” Dhandapani said. “And to see the dire situation these patients were in, it really just touched me to the point where we set up some research around that condition because these patients do really poorly.”

Unfortunately, it’s also difficult for doctors to treat, Dhandapani said.

“There’s not been any clear drugs that have worked with these patients,” he said. “Even surgery in many cases is not recommended.”

Finding an unexpected discovery

Inspired by their passion to help those suffering from intracerebral hemorrhages, Hess and Dhandapani began looking at remote ischemic conditioning, or RIC therapy, which is an experimental medical procedure that aims to reduce the severity of ischemic injury to an organ such as the brain by triggering the body’s natural protection against tissue injury.

“What we found was something very unexpected,” Dhandapani said. “We tried this treatment, remote ischemic conditioning, and what we found unexpectedly, is it actually started shrinking the blood clots in our mirroring models. We were using a mouse model of intracerebral hemorrhage. It was completely unexpected because RIC is basically just a blood pressure cuff, similar to the machines in stores that take your blood pressure.”

The treatment uses cuffs on both of the patient’s arms, he said.

“We just blow up both cuffs for five minutes and it’s like taking their blood pressure,” he said. “Then, we turn it off for five minutes and turn it back on for five minutes. We do that four times and that’s our whole treatment. It’s noninvasive. It’s very simple. It doesn’t cause any pain or side effects and what we found is doing that once a day for four days actually shrunk the blood clot. It was about a 70% reduction in the size of the blood clot.”

Dhandapani said he was astonished by the results.

“It was completely unexpected,” he said. “What we found is it was actually changing the immune system around, from this pro-inflammatory phenotype into this anti-inflammatory and reparative phenotype. So it’s causing a cell called macrophages, it’s part of your white blood cells, to actually go into the brain and start eating the clot faster.”

The results of their research were published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine and received a great deal of attention.

“As a result, it has led to three clinical trials around the world that are based on our work,” Dhandapani said. “I’m very proud of that because, as a scientist and a researcher, we all think what we’re doing is the most important thing in the world, but we also always want to help people. I think that’s why we get into science and get into medicine. We want to help other people. So, when you have a discovery from your own lab that’s kind of paved the way for three clinical trials, I take it as a badge of honor.”

The circle of mentoring continues

As a professor, Dhandapani also deeply values mentoring his students along the way.

He’s particularly proud of two individuals he’s mentored over the years: Dr. Kumar Vaibhav, his postdoctoral fellow, and Dr. Molly Braun, one of his former PhD students.

“I’ve had really good mentors through my career and I always want to pass that on to the people that I get to train,” Dhandapani said. “Seeing two of your students start to achieve their goals and the hopes that they had in science, in some ways that’s even more fulfilling for me.”

In fact, one of Dhandapani’s mentors when he first came to Augusta University was Brann.

“He was my PhD mentor and I actually trained with Dr. Brann,” Dhandapani said. “He really taught me how to be a scientist. He’s the one who showed me how to do this for a living and how to ask big questions and kind of be fearless. Honestly, I owe all my professional success to him.”

Ironically, Dhandapani met Brann through Mahesh.

“I’m not from this area. I actually grew up in Connecticut and, to be frank, I had never heard of Augusta, Georgia,” Dhandapani admitted. “I did my undergraduate and master’s degree at University of Connecticut and I started to look at where I should go do my PhD. One of my mentors at UConn, Bruce Goldman, gave me one name. He said, ‘You need to go talk to a guy named Virendra Mahesh at the Medical College of Georgia.’”

Mahesh was incidentally Goldman’s mentor in 1968.

When the two met, Dhandapani said he knew he wanted to come to MCG.

“But Dr. Mahesh said, ‘Listen, I’m retiring in the next year, so I’m not taking on any new students. But I’ve got this young, very smart guy. He’ll take new students.’ That man was Dr. Darrell Brann,” Dhandapani said. “So, I actually came here to work with Dr. Brann. That’s what brought me to Georgia in the first place. And, honestly, looking back, it turned out to be the best decision of my life.”

Augusta University

Augusta University