Simon Medcalfe, PhD, has been an educator for more than 20 years and has published dozens of articles. His most recent paper, “White Nose Syndrome in Bats and Infant Mortality in Georgia,” was particularly special because he worked on it with his sons.

Medcalfe, an economist and professor at Augusta University’s James M. Hull College of Business, read research by Eyal Frank, PhD, an environmental economist at the University of Chicago. The research focused on white nose syndrome and bats. Medcalfe brought up the article during a chat with his sons, Rhys and Sean.

Rhys, 24, earned his bachelor’s in wildlife sciences with a minor in fisheries sciences at the University of Georgia and his thesis paper was on bats. Before college, he had little interest in them, but his curiosity sparked during a mist netting, or bat catching, exercise in his mammalogy class. There, he handled bats for the first time.

“Bats became super interesting because of their small size yet long life spans. Some of the bats we caught were 20 or 30 years old,” said Rhys, who is pursuing a master’s degree in wildlife management with a focus in applied ecology at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. “As well as their unique way of navigating the world. I chose to study them at UGA because it was plausible to study them and be a full-time student and Georgia is unique in that white nose syndrome is moving south along the state, and we can see this change in bat populations as the disease moves south.”

Sean is double majoring in chemistry and environmental science at Luther College in Decorah, Iowa. He mentioned that his Geographical Information Systems class read the same paper and found it interesting. The class talked about how GIS applies to various research areas. One topic was the spatial application of white nose syndrome in bats and its impact on infant mortality.

“I am intrigued by the topic of one health,” said Sean, 21. “The idea that environmental health is intertwined with human health is such a fascinating topic. Oftentimes, it is topics that seem logical once you have seen the end result, but not anything that you think about beforehand, yet it can severely impact our lives.”

“Rhys knew he could find the bat information through the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, and I’ve done a lot of work in health outcomes, particularly with the Honors Program and social determinants of health,” Simon added. “Sean was interested, and I knew where to get the health data. I thought, ‘Oh, this would be a great paper to write together because it’s all our different interests all in one.’”

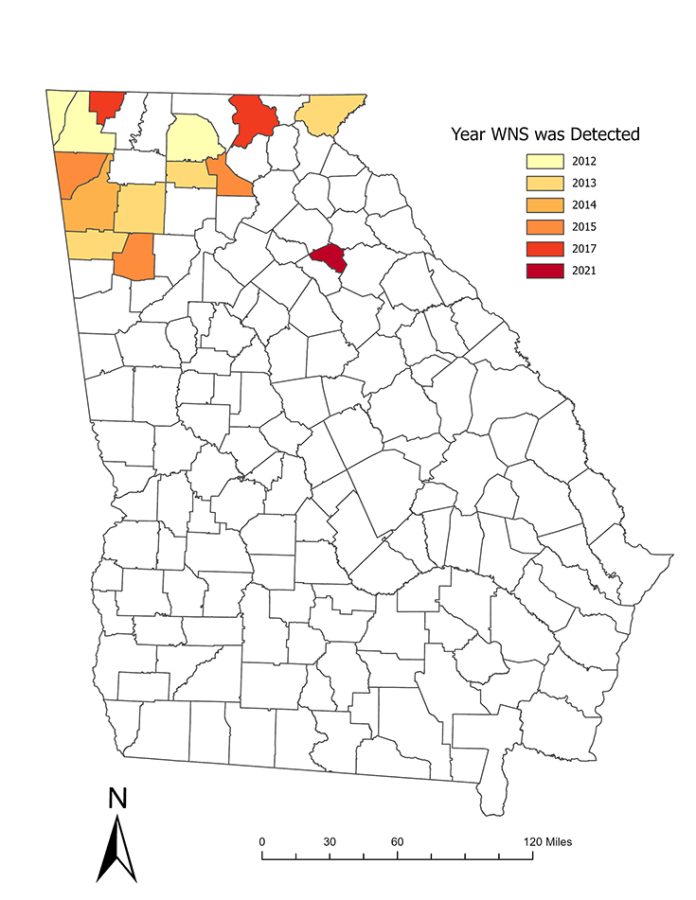

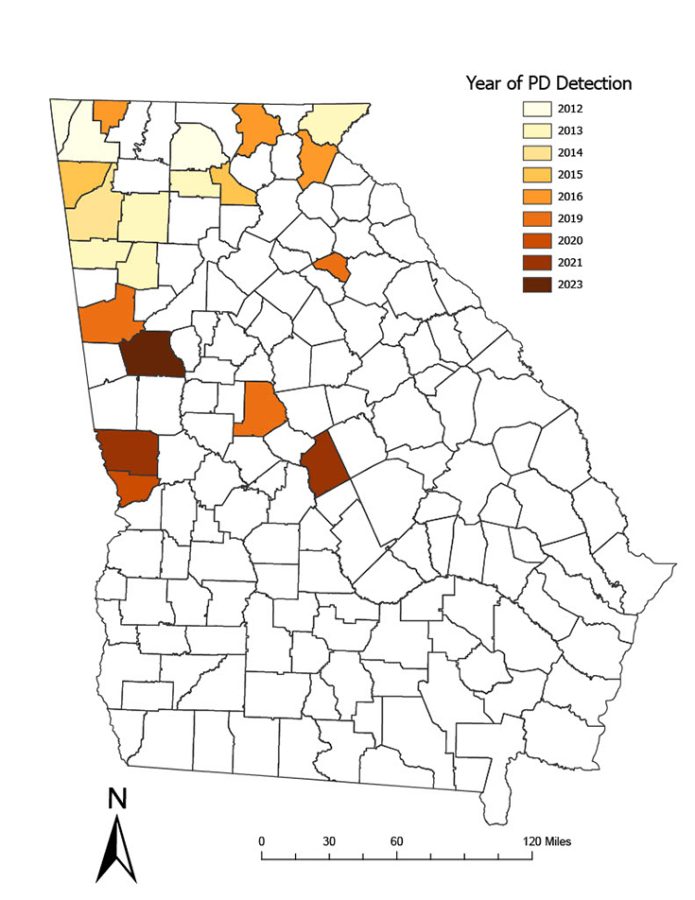

The three of them combined their skill sets and researched how white nose syndrome affects Georgia. Based on their findings, it’s a disease in bats caused by the fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans that can result in bat mortality rates of over 90%. WNS was discovered in three Georgia counties in 2012 and has spread to 14 counties as of 2023. The fungus has also been detected in an additional seven counties.

Biodiversity loss has been linked to human health outcomes including infant mortality and understanding those links in Georgia is important because it has one of the highest infant mortality rates in the nation, coming in at 42nd. Using panel data for 129 of the state’s 159 counties from 2014-19, the Medcalfes used a random effects Poisson regression model to estimate the relationship between detection of P. destructans, white nose syndrome and infant mortality. They found that counties where P. destructans and white nose syndrome are detected have higher infant mortality.

“P. destructans has come across from Europe but likely from contaminated caving materials and clothing,” Simon said. “It landed in New York and has traveled down the eastern seaboard and reached as far west as Washington State. It arrived in Georgia around 2012, 2013 and mainly affects cave-dwelling bats. It has a high mortality rate, close to 90% where we see the fungus that causes the white nose syndrome. Bats get a white nose from Pd, hence the name. The disease causes increased metabolism and early awakening from hibernation. This, associated with scarce food supplies, is what kills them.”

“It will take an integrated approach across disciplines to work together toward a solution. The Georgia Department of Natural Resources has published a response plan (dated 2016) that outlines steps to raise awareness of white nose syndrome, prevent or slow the spread of the disease, monitor and analyze bats, as well as managing natural resources such as caves.”

According to the Medcalfe’s research paper

Eyal Frank’s research suggests the relationship between white nose syndrome and infant mortality is through farmers’ increased use of pesticides to compensate for the loss of natural biological pest control through bats. Pesticides then run off agricultural lands and make their way into drinking water and the food supply.

According to the Medcalfes’ data, obtained from the U.S. Geological Survey, they found Georgia counties where white nose syndrome has been detected saw an average increased pesticide use of up to 41% between 2014 and 2017. By contrast, counties with no detection of white nose syndrome saw pesticide use increase by only 4%.

The World Health Organization defines One Health as “an integrated, unifying approach that aims to sustainably balance and optimize the health of people, animals and ecosystems. It recognizes that the health of humans, domestic and wild animals, plants and the wider environment, including ecosystems, are closely linked and interdependent.”

“It will take an integrated approach across disciplines to work together toward a solution. The Georgia Department of Natural Resources has published a response plan (dated 2016) that outlines steps to raise awareness of white nose syndrome, prevent or slow the spread of the disease, monitor and analyze bats, as well as managing natural resources such as caves,” according to the Medcalfes’ paper. “Although the plan includes the Georgia Department of Community Health it is only as it relates to rabies. This research suggests that such collaboration should be expanded to recognize the role of WNS on infant mortality and raise awareness of the connection between animal and human health. An alternative policy response may be to educate farmers, or provide incentives, to use alternatives to chemical pesticides. There is evidence that effectively designed incentives can change agricultural practice.”

While Simon’s primary focus relates to business and economics, his previous research has included social determinants of health impacting health outcomes. He mentioned a lot of issues that cause people’s poor health occur long before they see a doctor or have access to quality health care. Social determinants of health are the conditions where people are born, live and work and include topics usually of interest to economists such as income, education and the environment.

“Professionally, I was excited to link wildlife health to human health. A lot of my work is tied to ecosystem services or saving agriculture which in a roundabout way are correlated to human health, but the idea of a direct correlation was exciting.”

Rhys Medcalfe

Although the three live in different states, all of them were excited about working on this project together. Simon and Sean presented the paper at Luther College.

“While watching my father present, it was very cool to see him doing something that is in his wheelhouse,” said Sean, who also mentioned he learned about the publishing process. “I have often seen him around the home and in other normal family activities, but seeing him do something that was in a more professional environment was intriguing. It was great to see him in his flow and take control of a situation I have never seen him in.”

Rhys learned that these links between the work he considers, his work in wildlife management and his father’s work in human outcomes aren’t as different or hard to find as he once thought. He noted that they use similar models and also mentioned it was interesting to see the different angles that they all brought to the problem.

“I think, as a family we have a few more links that we hope to explore,” Rhys said. “Professionally, I was excited to link wildlife health to human health. A lot of my work is tied to ecosystem services or saving agriculture which in a roundabout way are correlated to human health, but the idea of a direct correlation was exciting.

“Personally, I think I was excited to combine efforts with my family and three stages of Medcalfe education – undergrad, graduate and professor – into one paper.”

Augusta University

Augusta University