When Dr. Lawrence D. Devoe was a young boy living in Chicago, he would wear his custom-made lab coat that had his name on it and make the hospital rounds with his grandfather, Dr. Louis D. Smith, a urologist.

Smith was chief of staff at his hospital, Devoe said, which made this special treatment possible. However, it was how Smith interacted with his co-workers and patients, the level of care and compassion that, as Devoe puts it, left a lasting and profound impression on the person he would eventually become.

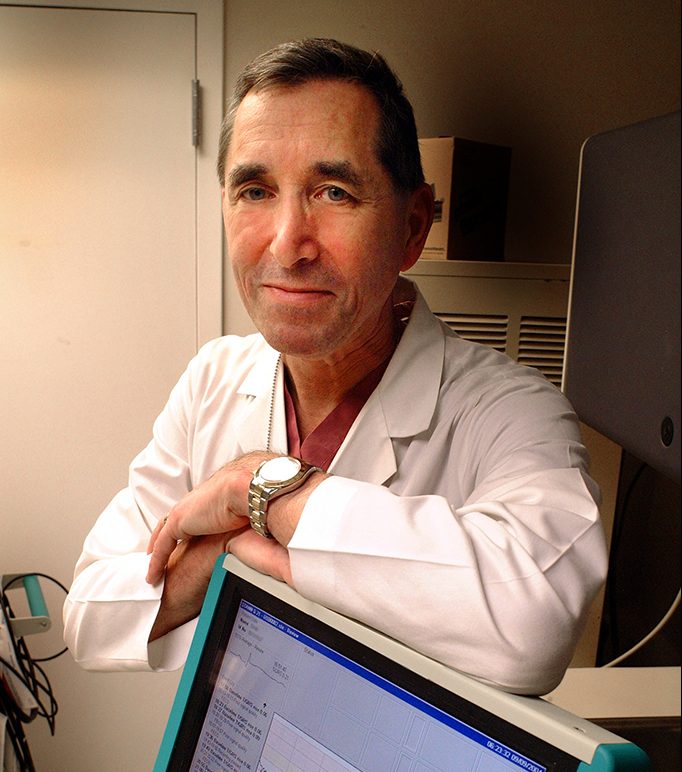

“I watched him in the operating room and I visited him in his office when he was seeing patients. In addition to being a great physician, he was also a kind of a renaissance man,” said Devoe, who is officially retiring from the Medical College of Georgia on June 30. “He inspired me to get interested in all the things in life that he was interested in, and in which I still am interested, like classical music, sports, and Shakespearean dramas.

“My grandfather received his medical degree in 1911 and there were no formal internship or residency programs back then,” he said. “You had to find somebody who was in the specialty you wanted to do and you would apprentice yourself out to that person until he thought that he had taught you everything that he knew.

“He really tried to discourage me from going into medicine because of what he had to go through in the early days of his career because doctors weren’t well paid in that era,” he said. “Everything was cash or barter. People just paid what they could, and it was a tough living. He eventually did come around to accept my decision to become a doctor.”

Devoe was motivated to use the knowledge his grandfather had and the compassion he displayed to also work for him. After attending Harvard University, he went back to Chicago and earned his medical degree from the University of Chicago, Pritzker School of Medicine in 1970 and then completed his residency in 1976 at University of Chicago Hospitals, obstetrics and gynecology, and his fellowship in maternal-fetal medicine in 1979.

Devoe continued to spend a lot of time with his grandfather, who lived long enough to see Devoe graduate from medical school and finish his training. Devoe said he was the last person with his grandfather when he died.

“I admired him and respected him … he was a great person and I don’t think they make them like that anymore,” Devoe said. “I watched how he dealt with patients … that made huge impression on me. I just watched how he dealt with patients one-on-one, and how he advised them, counseled them, how he presented good news and how he broke bad news. When you witness these things at a young age, they never leave you. And he had an incredible work ethic. I saw how hard he worked, but I thought that was normal.

“The world has changed a good bit in the past 100 years, but the values he passed on to me, those were things that are timeless and really had a great deal to do with the person that I became.”

Devoe was a faculty member in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Chicago for seven years before making the move to Augusta. He said he felt predestined to move down south because his grandfather was a Southerner from Louisiana who never lost his southern accent while living up north.

“I’ve lived more than half my life now in the south and I married a southerner, so I guess now I really am more a naturalized son of the south than I am a yankee,” Devoe said.

Mentorship has always been very important to Devoe, who has educated thousands of medical students and trained more than 150 OB/GYN residents and 15 maternal-fetal medicine fellows. Devoe had discussions with his early career mentor Dr. Fred Zuspan, who was the chair of the Medical College of Georgia before becoming the chair of OB/GYN at the University of Chicago, about what Augusta was like. Devoe heeded Zuspan’s suggestion of coming and trying it out for a few years. With the help of colleagues such as Dr. Paul McDonough, whom he also considers a mentor, and marriage to his wife, Anne, a South Carolinian, Devoe has turned a trial run into 37 years.

He admits he looked at other jobs from time to time, but he never found a better one. Coupled with being surrounded by good people and the opportunities he had here, he “dropped anchor” and turned into a full-time Southerner.

During his time in Augusta, he was a Brooks Professor, chairman of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the Medical College of Georgia from 1995 to 2006 and chief of the Section of Maternal-Fetal Medicine for 23 years.

He has twice received the MCG School of Medicine Distinguished Faculty Award for Institutional Service and served as the 71st president of the South Atlantic Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists in 2008-09.

Devoe said he was a curious child growing up and “curious children ask questions. And when they can’t get answers, they start doing their own investigation.” It was that curiosity and finding out how things work, should work or how they can be improved upon, that stayed with him his entire life.

Devoe said he has had an unparalleled opportunity in Augusta in terms of academic work and research, which includes computer applications in fetal monitoring, enhanced fetal assessment and new methods of labor induction. He was also the principal investigator on a study that monitored ST segment of the fetal EKG during labor, a novel method to reduce the risk of babies dying during labor or being born with hypoxic brain damage.

Devoe credits his tenure as editor in chief The Journal of Reproductive Medicine for the past 16 years to helping inspire some of the work he’s accomplished here. He has also authored or co-authored more than 300 scientific articles, abstracts and book chapters.

“To do what I would call cutting-edge work both in the clinical and basic sciences, would actually be precedent-setting for anybody in any department,” he said. “If you look at a curriculum vitae, it’s just a document that shows how you spent your time and what you’ve done with your life. And I still occasionally look at mine and wonder, ‘Who is this person?’ It’s been a very productive run.”

His mantra for research has always been “let’s find out.”

“With everything that I’ve been involved in during my research career, I always first look at issues that I think are important now and will be important tomorrow and in five or 10 years from now, because I’ve always had five- and 10-year plans of what I’m going to do,” Devoe said. “A lot of the work I’ve done has really been in the area of applied biomedical engineering. A good engineer will take on a project, see it through to its completion and if they are satisfied that it works, they’ll move on to the next thing, and that’s what I’ve always done.”

Over the years, Devoe slowly started stepping away from some of his responsibilities. After attending 10,000 births, he stopped delivering babies 10 years ago and recently shared a cry after saying goodbye to his last patient. Devoe had actually planned on retiring last year but stayed to continue helping the faculty in his specialty.

While he feels he could have still done his job, Devoe said he had accomplished everything he had set out to do years ago. He will miss the people he’s cared for and worked with for almost four decades at the Medical College of Georgia, “because when you work with a closely knit group of people, they’re just like an extended family. … And when you have people like that around you, it’s really not work.”

His retirement plans include traveling with his wife to see family spread out across the United States while also getting a chance to do more writing, see productions at the Metropolitan Opera in New York City and visit museums at every opportunity.

He fondly looks back on a vocation that fulfilled his aspirations as a medical professional.

“I never use the word career because that just doesn’t have the right sound,” Devoe said. “I like to use the word vocation which means ‘calling.’ In reality, if you have been fortunate, what you’re really doing is fulfilling a calling rather than pursuing a career. And that’s what happened to me. I’ve talked to medical students about their lives. I said, you know if you choose a career; it’s even better if your career chooses you, because that’s what happened to me. And if it happens to you, then that’s really what you should be doing.”

Augusta University

Augusta University