The average age of the global population is increasing, and with that comes an increase in the number of people being diagnosed with dementia, an umbrella term for a collection of cognitive, functional and behavioral symptoms caused by neurodegenerative diseases.

The main culprit is Alzheimer’s disease, which accounts for 60-80% of dementia cases. In fact, the National Institute on Aging predicts the number of Americans living with Alzheimer’s will nearly double to 13.9 million over the next four decades, with age being the biggest risk factor.

As bleak as that might seem, what’s even more troubling is that Alzheimer’s is the sixth-leading cause of death in the U.S. as of 2024, according to provisional data from the National Center for Health Statistics.

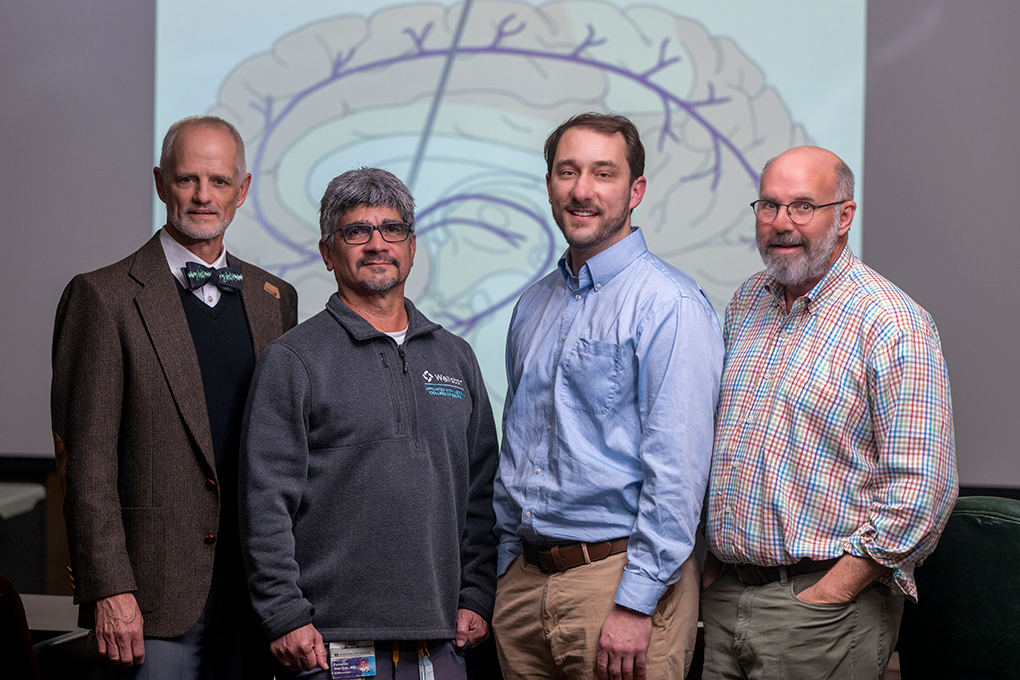

In hopes of combating those statistics and improving the quality of life for those living with the condition, a team of neuroscientists at the Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University has recently received approval to start human clinical trials on a proposed treatment using deep brain stimulation, or DBS.

What is deep brain stimulation?

Most commonly used for movement disorders, DBS is a treatment that involves implanting tiny wires with electrodes into the brain that send signals to that specific area. The extension wires, or leads, connect to a subdermal battery pack that allows neurologists to control specific nerve signals.

The MCG team’s target area of the brain is the nucleus basalis of Meynert, which plays a crucial role in memory, attention and cortical function. It’s also only five millimeters away from one of the targets for Parkinson’s disease.

“The nucleus basalis of Meynert was one of the first sites implicated in Alzheimer’s dementia 50 years ago,” said David T. Blake, PhD, professor in the Neuroscience and Regenerative Medicine department at MCG and principal investigator of the trial, who has been studying DBS’s effect on Alzheimer’s disease for the past decade. “It declines in function as well as in size as cognitive status declines, and that occurs both with normal aging and, more significantly, with Alzheimer’s dementia. People have looked at this target for many years, and the intermittent stimulation was the first time that we had the capability to lead to cognitive improvement by addressing the nucleus.”

DBS was first approved by the FDA in 1997, and since the early days of its usage, doctors have gained insight into its limitations. Fernando Vale, MD, department chair and professor in MCG’s Neurosurgery department and member of the trial group, compares the human brain to a massive supercomputer and DBS as a pacemaker of sorts.

“We have figured out that if you push the electricity and the connections too much, you shut down the system instead of making it better. That’s when Dr. Blake’s idea came to fruition. He came up with the idea of adjusting what we’ve learned in this process, and a simple adjustment can lead to completely different results,” he said.

“The idea here is to use brain plasticity, brain recovery, to reconnect and allow the brain to function on a better level for a longer period of time,” he continued. “We’re not claiming that we’re curing – this is not a cure, but if we can delay the onset for three, five, seven years, that’s a win-win for everybody. The patient, the family and society.”

Preliminary research using animal models

Blake’s initial DBS research on Alzheimer’s began 10 years ago using monkey models. He and his team would stimulate the nucleus basalis of Meynert and then observe whether this improved the monkeys’ working memories when completing a task.

“They would touch a touch screen, and they have to remember what they touched and then touch it again a few seconds later,” Blake recalled. “As we started stimulating them and testing them, we found that when we delivered intermittent stimulation, so stimulating them for about a fraction of each minute, the monkeys would do a little bit better at the task, and we got an NIH grant to study that.”

The MCG team also worked with a research group from Vanderbilt University that was able to record the monkeys’ brains to track cognitive function while they were completing these tasks.

As the experiments progressed, the baseline working memory capabilities of the monkeys improved dramatically. That’s when Blake realized the amount of potential for this treatment to benefit people with dementia.

To test this theory further, the team also used several different mouse models to test the treatment and measure the effects on the brain. What they found was the cerebral cortex received a “jump start” from the stimulation.

“When we stimulate, we cause a dramatic increase in a chemical called acetylcholine in the entire cerebral cortex, and that leads to a large change in the blood flow in that area,” Blake said. “So each time we deliver the intermittent stimulation, we cause a flood of acetylcholine and blood flow to the cerebral cortex that lasts about 10 seconds, and then we have to let the system recover for about a minute. Then we do it again, and we repeat this once per minute for roughly an hour, and when we do that, we get the cognitive effects.”

When Vale began collaborating with Blake’s team about six years ago, they started doing the tests on monkeys that were about 25 to 30 years old; the equivalent of the common age at which humans start getting diagnosed with Alzheimer’s.

“We wanted to see if it worked in a geriatric population, and we got the same magnitude of effects in the older monkeys. We were able to optimize the stimulation a little bit by playing with the parameters of how long the stimulation is on, how long we let the brain recover and how long we apply it,” Blake explained. “On the basis of that, we felt pretty confident that our preclinical data was properly in hand to go into human trials.”

Blake serves as a collaborator and consultant for trials using DBS on Parkinson’s disease patients at other universities, but he noted it hasn’t been tested on Alzheimer’s patients yet, which he and his team are eager to begin at MCG.

The trial

Starting in January 2026, six patients between the ages of 65-85 with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease will be recruited from the Wellstar MCG Memory Clinic. If eligible for the trial and enrolled, they will undergo 50 minutes of DBS of the nucleus basalis of Meynert every day for two years. This will be done remotely by the patient or their caregiver.

“We’re giving the brain a little interval workout,” Blake said. “10 seconds of really high activation, followed by 40 seconds to recover and get ready for the next 10 seconds, and we repeat that for about an hour.”

Although the brain isn’t a muscle, it’s similar in the way that it needs cognitive “exercise” to stay strong through neuroplasticity. To build muscles, a common practice is to lift a heavy amount of weight for a short amount of time and then incorporate a period of rest before starting the next set. Blake and Vale compare this to their intermittent DBS approach.

“If you don’t rest, you’ll destroy the muscle, and in previous DBS investigations, we learned that if we push it and leave the stimulation on, cognitive function was not improving but regressing,” Vale said.

Six other patients will serve as the control group and not receive DBS. That group will document the progression of Alzheimer’s disease under the normal standard of care.

Assessments will be performed at the onset of treatment, after four weeks of intervention and every six months throughout the two-year study.

“This should be their only dementia, and they shouldn’t have a major psychiatric illness. They should be relatively uncomplicated memory patients who come in when they’re at the point in their memory disorder where they’re starting to lose some of the activities of daily living, but they still maintain most of them, and we want to extend that as long as we can,” Blake said.

Blake noted that the nucleus basalis of Meynert has been targeted before in other DBS trials, but not with this research team’s pattern of intermittent stimulation.

“We went into the animal models to try to get cognitive improvements and to try to study the physiological effects, and that’s what brought us to the intermittent stimulation. We’re bringing that back to the human clinic,” he said.

“In the animal studies, we saw prominent improvement in the first four weeks, and I expect that to happen in this trial,” he continued. “The biggest concern for me is what will happen over two years. We’ve done this in dozens of mice and monkeys – every animal has cognitive improvement without fail. It’s really striking and large. I think the human patients will show the same thing, but we’ve got to see what happens over a two-year period because that’s how we’re going to help people who have Alzheimer’s. We need to preserve their activities of daily living long term.”

The goal

The main goal of the study is to determine whether DBS can sustain or improve cognition in Alzheimer’s disease for at least two years.

“We want the patients to have the same clinical dementia ratings or better two years from now as they did when they came into the clinic for the first time,” Blake said. “These are patients for whom we would expect there to be a cognitive decline in those two years. In fact, it would be very unusual for them not to show a cognitive decline in two years. We hope that our stimulation will give them that capability.”

Success would be defined as at least half of the patients in the DBS group meeting the two-year preservation of cognitive status criteria. If that’s the case, then the team would want to set up a multi-site trial with randomized patients.

“Meaning all the people who entered the trial would get surgery. Half of them would not get stimulated for the first six months, half of them would and then we would un-blind them after six months and track their progress for two years,” Blake said. “If we had good data from that as well, that could lead to FDA approval.”

Augusta University

Augusta University