In the tough war against glioblastoma, scientists are taking a cue from viruses on how to make the aggressive cancer more vulnerable to treatment.

Their target is SAMHD1, a protein which can protect us from viral infections by destroying an essential building block of DNA that viruses and cancer need to replicate.

But they’ve found SAMHD1 also has the seemingly contradictory skill of helping repair double-strand breaks in the DNA that if unrepaired can be lethal to any cell, including a cancer cell, and if mended incorrectly can result in genetic mutations that produce cancer.

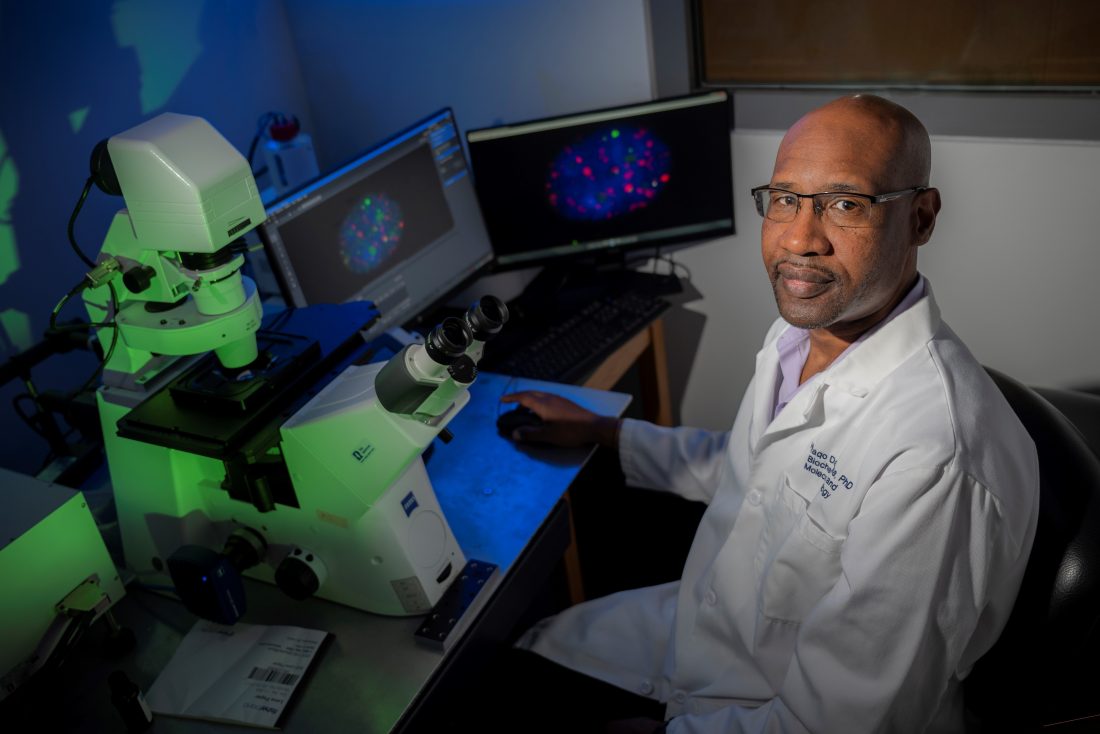

“When the DNA breaks, that is what actually interrupts the DNA replication and also the synthesis of proteins, so a double-strand break is lethal for cells,” says Waaqo Daddacha, PhD, cancer biologist in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at the Medical College of Georgia.

Cancer cells, which are reproducing much more rapidly than most normal cells, are replicating even faster, so are impacted even more by these DNA breaks, which is why fundamental therapies like radiation and some chemotherapy drugs used to treat cancers make these lethal breaks.

However, the aggressive brain cancer quickly becomes treatment-resistant and the average survival remains at about 15 months, Daddacha says.

Now Daddacha and his colleagues report in the journal Cancers their surprising finding that in glioblastoma in humans both SAMHD1 and the essential DNA building block dNTP, which it can destroy, are highly expressed, indicating SAMHD1’s likely importance to the brain tumor’s aggressiveness and raising questions about what it’s doing there.

They were expecting high levels of dNTP because cancers need a ready supply of this building block to keep up their rapid pace of replicating and spreading, Daddacha says. Since dNTP levels were high, they were also expecting low levels of SAMHD1 would be present and that increasing its levels would help protect against glioblastoma.

They would find the opposite to be true, indicating that like with so many innate properties cancer usurps, glioblastoma likely alters the function of SAMHD1.

“Theoretically, since cancer cells divide rapidly and need more dNTP to do that, it seems logical that they would need less of this protein,” Daddacha says. It also seems logical that SAMHD1 would be protective against cancer, like it is against viruses, Daddacha says.

Based on what they found, the scientists instead decided to reduce SAMHD1 levels, and that’s where viruses’ skill at eliminating the multitasking protein came in.

Viruses deploy the protein viral protein X, or Vpx, to literally chop up SAMHD1 so they will have a ready supply of dNTP, a virus skill set first identified in HIV. So, the scientific team used a virus-like particle, called a vector, to deliver Vpx directly to the glioblastoma. These types of viral vectors already are used in people to deliver a variety of therapies, including some of the COVID-19 vaccines.

They found by reducing SAMHD1, Vpx sensitized the brain tumor cells to the chemotherapy drug veliparib, which helps block DNA damage repair by cancer cells, and slowed cell growth of this fast-growing brain tumor. It also made the tumor cells more sensitive to temozolomide, or TMZ, another chemotherapy drug often used for glioblastoma, which disrupts the cell’s DNA structure with the idea of killing the cell. By reducing SAMHD1, Vpx appeared to also reduce the innate skill called homologous recombination, which SAMHD1 promotes, and which enables a sound repair of double-strand breaks that also helps avoid cell mutations that could enable cancer.

Reducing SAMHD1 levels enabled the combination therapies, including radiation, used for glioblastoma to work more synergistically as intended, and reconfirmed SAMHD1’s role in enabling glioblastoma’s usual treatment resistance, the scientists write.

In a mouse model with the human brain tumor cells, they found that reducing SAMHD1 slowed tumor growth and genetically knocking out SAMHD1 improved survival, the scientific team reports.

As another piece of the emerging puzzle, when the scientists removed SAMHD1, dNTP levels did increase some but not dramatically, like they have seen in some other cell types, more evidence that while SAMHD1 still has some impact on degrading this DNA building block, in this scenario, it clearly has yet another function, Daddacha says.

He suspects that the real benefit of high levels of SAMHD1 to glioblastoma is “self-protection” relying most on the protein’s innate ability to help repair double-strand DNA breaks.

There is overwhelming evidence that glioblastoma’s skill at repairing double-strand DNA breaks is key to its treatment resistance, which makes targeting the repair process logical, Daddacha says.

One of the ways cancer takes over a protein for its own purposes is by modifying its function so, for example, it could shift SAMHD1 into primarily DNA repair mode and reduce its natural ability to degrade dNTP, and Daddacha suspects glioblastoma is changing SAMHD1’s function.

“Clearly it’s using it to survive,” Daddacha says, which is likely at least a part of how glioblastoma is so tenacious, and a piece of the big puzzle needed to one day better treat the deadly cancer.

Their findings indicate that SAMHD1 can be targeted and eliminated using the viral protein Vpx in glioblastoma, Daddacha says, but notes that much work remains before the findings and the tool can be used to improve glioblastoma treatment.

Next steps include learning more about what SAMHD1 is doing in glioblastoma, and how high levels of it can coexist with high levels of dNTP, which it should destroy.

“We will try to discover if SAMHD1 is actually degrading dNTP in cancer cells,” says Daddacha. It may be that the high levels of SAMHD1 may also help keep high levels of dNTP in check, he says, because everything needs balance.

They also are refining the safe, specific technique of delivering Vpx with the idea that one day it could also be used in people, and to determine if the technique impairs glioblastoma’s growth in other ways as well.

Glioblastoma is a lethal cancer that is always considered as an aggressive, stage 4 tumor at diagnosis with patients living an average of 15 months after diagnosis, Daddacha says. By the time symptoms like headaches and seizures emerge, the tumor already has progressed.

Standard treatment includes surgery to remove as much of the tumor as possible, radiation and chemotherapy.

SAMHD1, or sterile alpha motif and HD domain-containing protein 1, is omnipresent in cells, including in our brain cells. It is believed to keep viruses like HIV-1 from replicating by cutting and destroying dNTPs, or deoxynucleoside triphosphates, which normal cells, cancer cells and viruses all need to reproduce. “We make our DNA with a chain of dNTPs,” Daddacha says. SAMHD1 also likely normally works to help regulate the amount of dNTPs the body needs, he says.

While working on his PhD at the University of Rochester, Daddacha was part of the team that discovered that SAMHD1 degrades the DNA building block dNTP. While doing his postdoctoral studies at Winship Cancer Institute at Emory University in Atlanta, he further explored SAMHD1’s role with DNA and found it actually has a key role in the DNA repair pathway. Daddacha joined the MCG faculty in 2019.

The research was funded by the National Cancer Institute.

Read the full study.

Augusta University

Augusta University