Even though students have been complaining about the cost of textbooks for about as long as textbooks have been in use, recent numbers from the American Enterprise Institute paint a shocking picture: an 812 percent increase in the cost of textbooks since 1978. That’s a bigger jump than the increases in tuition, housing, or health care.

And that increase is hitting students in more than just the pocketbook. According to a report issued by the U.S. Public Interest Research Group, 65 percent of college students choose not to buy a textbook because it’s too expensive, and 94 percent of those say that they suffer academically because of it.

“They’ve done all kinds of studies and found that oftentimes students can’t afford their textbooks. So they’ll start the class without textbooks, and then they get behind,” said Melissa Johnson, Librarian Assistant Professor. “They’ll start borrowing books, but by then it’s often too late.”

Johnson is the Library Coordinator for Affordable Learning Georgia, an initiative of the University System of Georgia that aims to increase access to a college education by making educational resources more affordable through support of the adoption, adaption, and creation of Open Education Resources (OER), freely accessible, openly licensed materials that are used for educational purposes.

Dr. Robert Bledsoe, Assistant Chair, Department of English and Foreign Languages, is the program’s Campus Champion.

“Students have had to make life choices, and the life choice was not to buy the text book,” he said. “We still walk around with this vision of college as an elite institution, and though that changed in the sixties, we haven’t gotten around to thinking about the situation of the majority of students, who are going to school but maybe have a part-time job with little financial support. At least at the undergraduate level, this is still where we’re very much at.”

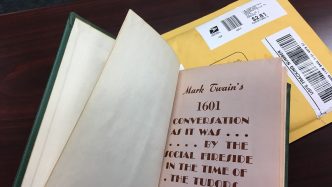

To illustrate one of the many frustrations students experience, he picked up a literary anthology that was about as thick as a box of Kleenex.

“We make them buy this, which is actually the shorter version, and they read maybe a tenth of it,” he said. “That’s not a satisfactory feeling.”

When the team-taught humanities program was changed from two four-unit classes to two three-unit classes, the team of instructors took advantage of the opportunity to utilize the Affordable Learning Georgia grant to create and gather their own materials.

Previously, students could spend as much as $500 on books and materials for the course.

Though the move worked for the humanities courses, getting the faculty and students to transition to nontraditional study materials, whether they’re OERs or articles or smaller books, isn’t always easy.

“I think GRU has been much more reliant on textbooks than I remember in my undergraduate education,” Bledsoe said. “At a certain level, a lot of classes just had regular books, where a lot of ours, even upper division classes, tend to rely on anthologies or published textbooks.”

The adjustment to more affordable alternatives tends to be more difficult in the humanities because of copyright issues, Bledsoe said. Unlike their counterparts in the sciences, humanities teachers are often using materials that someone has ownership of – images of art works, recordings of musical performances, or literature. Even translations of classic works in the public domain have issues, since many were published over a hundred years ago, when language was used differently than students are used to it being used now.

While Affordable Learning Georgia is an organized effort to change things at a state level, teachers have been working to alleviate the burden of textbook costs for years.

In December, Dr. David Hunt, Assistant Professor of Sociology, was recognized at the initial meeting of Affordable Learning Georgia’s “Symposium on the Future of the Textbook” for his efforts in adopting the use of an open access textbook for his Sociology 1101 course.

He started using the OpenStax Sociology book during the summer of 2012, and according to the University System of Georgia, he’s saved his students more than $11,000.

Supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Rice University among others, OpenStax College is a nonprofit organization committed to improving student access to quality learning materials. They produce several peer-reviewed texts in a variety of formats that are either free or, in the case of a printed book, at cost.

“I started talking to textbook publishers asking if they had anything cheaper, and they started giving cheaper versions. But it still wasn’t really, really cheap,” Hunt said. “Then I was contacted by the OpenStax people to review their intro sociology book. I reviewed three or four chapters for them, and once I saw the quality and the fact that it was free, I said as soon as this is available, I’m going to use it. And I did.”

The reasoning against OERs, that the cost of vetting the authors and the material is expensive, is something Hunt rejects.

“The OpenStax people are doing the exact same thing, so that’s really not an argument,” he said. “They haven’t made that argument because they can’t.”

As Interim Director of Distance Education, Hunt is representative of a new breed of educator. He teaches completely online, and his intro class uses the free sociology book.

“Students have the flexibility to study whenever and wherever they can,” he said. “They don’t have to pay extra money to do it, so to me, it’s gotten to the point where students can learn sociology as they need to instead of how we’re forcing them to.”

The traditional model of education, he said, is “you come and you sit and you listen to me tell you things the way I want to tell you things.” The newer models are, “you come and let’s start exploring some of these things, and you need to be doing it on your own, and here’s how you can do that.”

“That’s a very different model of education, but it’s an exciting one,” he said.

For more information about Affordable Learning Georgia, click here.

Augusta University

Augusta University