It likely came as a shock to many yesterday when it was announced that both Koreas—North and South—would march under a single flag at the 2018 Winter Olympics. The two countries, long considered the bitterest of rivals on the international stage, have little to celebrate jointly.

Why then would they choose to march together, and why now?

“The official position of both North and South Korea is that the Korean peninsula should be unified at some point,” explained Dr. Andrew Goss, chair of Augusta University’s Department of History, Anthropology, and Philosophy in Pamplin College. “They both acknowledge that the split of the Korean nation, which occurred during the Cold War, is unnatural and should be undone.”

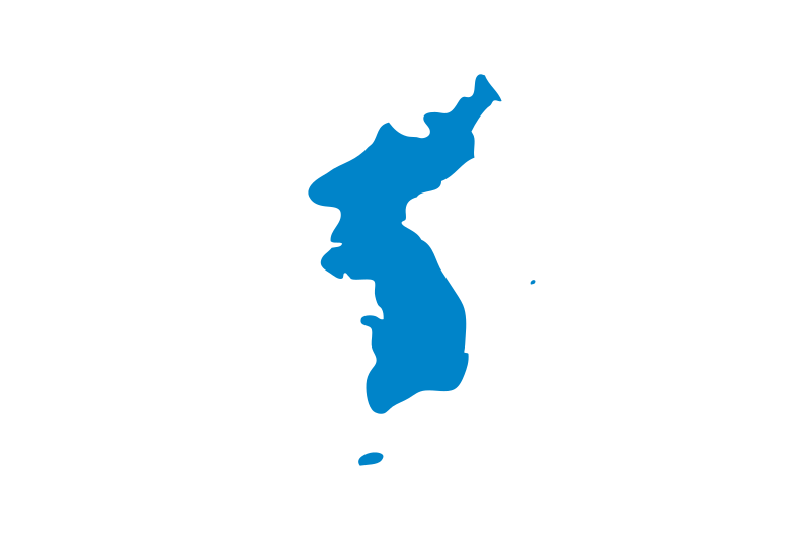

The shared belief has brought the two nations (briefly) closer together in the past. In fact, this isn’t the first time the two Koreas have marched under a single Olympic banner. The unification flag, an image of the Korean peninsula in blue set against a field of white, was first used in 1991 when the two countries competed as a single team in the 41st World Table Tennis Championships in Chiba, Japan.

The two Koreas have worked together in other, potentially more meaningful ways throughout the years as well.

“In the 1980s, the South Korean government began pursuing various efforts to reconcile the two halves of the peninsula, which has led to numerous efforts to cooperate in smaller and bigger ways,” Goss said.

These efforts included the Sunshine Policy of Kim Dae-Jung, the former president of South Korea, which saw real economic cooperation between the two Koreas.

Moon Jae-In, South Korea’s current president, has actively campaigned to revive the Sunshine Policy wherever possible, and has remained committed to the idea of improving the relationship between the two countries.

While encouraging, Goss said that the choice to march under a unified flag was “low-hanging fruit” in the diplomatic exchanges between the two countries. Kim Jung-Un’s regime has been extremely vocal with its provocations in the past several months. All signs point to those provocations continuing.

Even so, South Korea hasn’t given up on its northern neighbor, even in the face of international opposition.

“One thing we’ve learned in the last year or so is that nobody is in a position to make North Korea act normally,” Goss said. “The International community’s desire to maintain peace on the Korean peninsula, by maintaining the status quo of the two Koreas, is being played against South Korea’s wish to talk about reconciliation and unification.”

Augusta University

Augusta University