Ninety-three-year-old William “Willie” Nelson walks from his home in Evans, Georgia, to the train tracks each and every morning, while enjoying television and visiting with his family through the rest of the day.

He feels better than he’s felt in a long time. But that certainly wasn’t the case several months ago.

Last summer, the World War II veteran was serving as an usher at Warren Baptist Church, something he does every Sunday without fail.

Suddenly, Nelson sunk to the floor and collapsed. Thankfully, several medical professionals who were there at the church as it happened were able to help him get help.

Nelson’s stepdaughter, Terry McBride, works at Augusta University in the office of Dr. David Hess, dean of the Medical College of Georgia. She has been entrusting the care of Nelson to AU Health for years, and Dr. Thad Wilkins, his primary care physician, picked up on the fact that Nelson’s health problems were cardiac.

Looking out for ‘Number One’

Wilkins referred Nelson to Dr. Kimberly Atianzar, a structural cardiologist who had recently started practicing at AU Health. Atianzar determined Nelson needed an aortic valve replacement in his heart.

“It was the first time they’ve done this procedure as a team here,” McBride noted, pointing out that the doctors and nurses who treated Nelson often called him “Number One” since they couldn’t say his name at times due to patient confidentiality. “Number One” is a name Nelson embraces with pride, and he was beaming when his stepdaughter brought it up.

The particular procedure Nelson was “Number One” for at AU Health is a transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR). This means the bioprosthetic valve is replaced inside of the native valve going through the artery instead of doing open-heart surgery.

Atianzar was teamed up with another new physician, Dr. Richard Lee, the new chief of Cardiothoracic Surgery, who said there has been a “revolution” in treatment of valve disease in the U.S. in the last few years.

“I’ve never seen anything like it in any field,” Lee said. “It’s changed the treatment of valve disease and helped patients who wouldn’t be able to [receive treatment] otherwise and allowed them to live longer.”

Prior to coming here, Lee performed many such procedures at Saint Louis University, as did Atianzar at Swedish Heart & Vascular Institute. Their experience with this cutting-edge procedure has allowed them to bring it to AU Health. They’re now doing “at least two” of these a week, according to Atianzar.

Atianzar did some tests on Nelson in January and found he would be a good candidate for the mitral valve replacement. As a longtime employee here, McBride said she had full faith they would take good care of her stepfather.

Valve replacement at an early age

About that same time, a 24-year employee, Barbara Miles, who is a charge capture analyst in AU Health’s Revenue Integrity Department, had a similar issue with one of her loved ones.

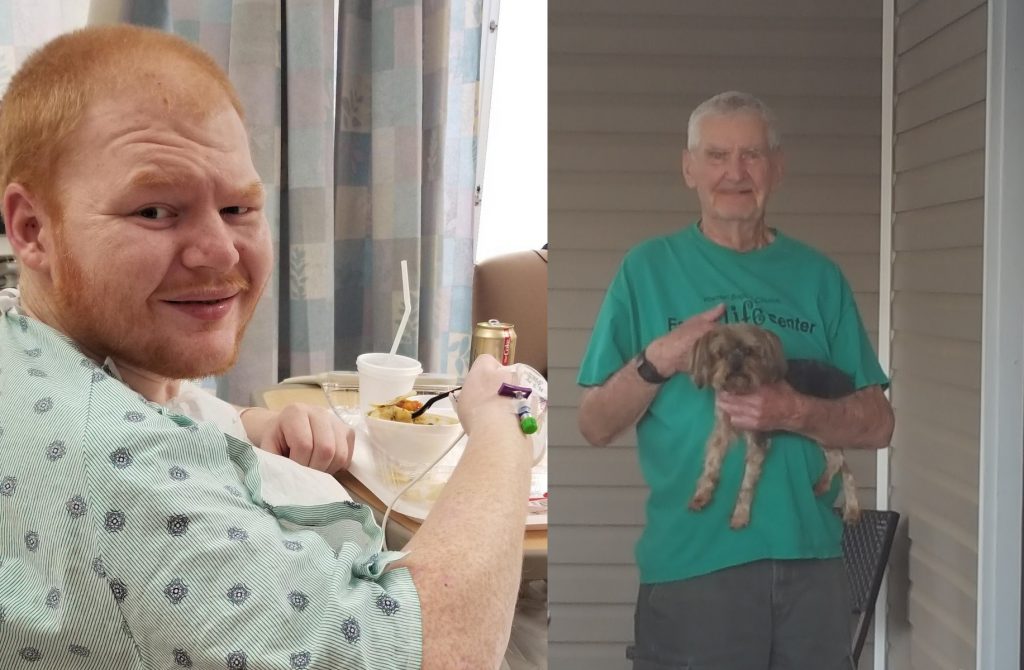

Her son, James Lawrence, had a synthetic mitral valve that had been placed over a decade ago, and he was due to get it replaced again. At the time, 20-year-old Lawrence went through open heart surgery after having gone through a multi-system organ failure the year before – this was his second surgery after the tricuspid valve had been replaced at age 19.

Miles remembers the words of the attending surgeon Dr. Vijay Patel years earlier: “’I won’t be the one that takes his life.’ He really didn’t think [Lawrence] was going to make it.”

Even so, “They told me there was a 95% chance that he would die without surgery,” Miles said.

However, the surgery caused lots of complications and the chances of Lawrence (who had also suffered from a traumatic brain injury in the meantime) surviving a third open heart surgery were low, due to scar tissue.

“It’s much more dangerous to open up and take out the valve, especially after prior heart surgery,” said Lee.

On top of that, there was a good chance that Lawrence, now 31, might fall after surgery due to his brain injury, putting him at even higher risk.

Once Miles met with Atianzar and was presented with this new option, she felt like she had just received a “miracle.”

“Dr. Atianzar and her team were the answer to my prayers, literally,” she confessed. “I was so fearful of open-heart surgery.”

Sure enough, as Atianzar described it, “It went really well and he went home later that week, and he didn’t have to re-do surgery.”

Six weeks after the surgery, Lawrence – who is gradually improving mentally – has had two follow-up appointments and is doing quite well.

On the road again

As for “Number One,” he is back to his normal routine nearly six months after the procedure, making that daily walk from his home to the train tracks, and serving in church every week.

“He goes about his day-to-day life, and our goal is to keep him in his home as long as he can possibly be there,” said McBride.

Nelson’s routine follow-ups have all gone well, too.

“Number One” sees his next stop as heaven, but until then, as he said with a laugh, “I’m going to just keep on keepin’ on.”

Augusta University

Augusta University