Patients diagnosed with the most common form of leukemia who also have high levels of an enzyme known to suppress the immune system are most likely to die early, researchers say.

High levels of this enzyme, indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase, or IDO, at diagnosis also identify those who might benefit most by taking an IDO inhibitor along with their standard therapy, they report in the Nature journal Scientific Reports.

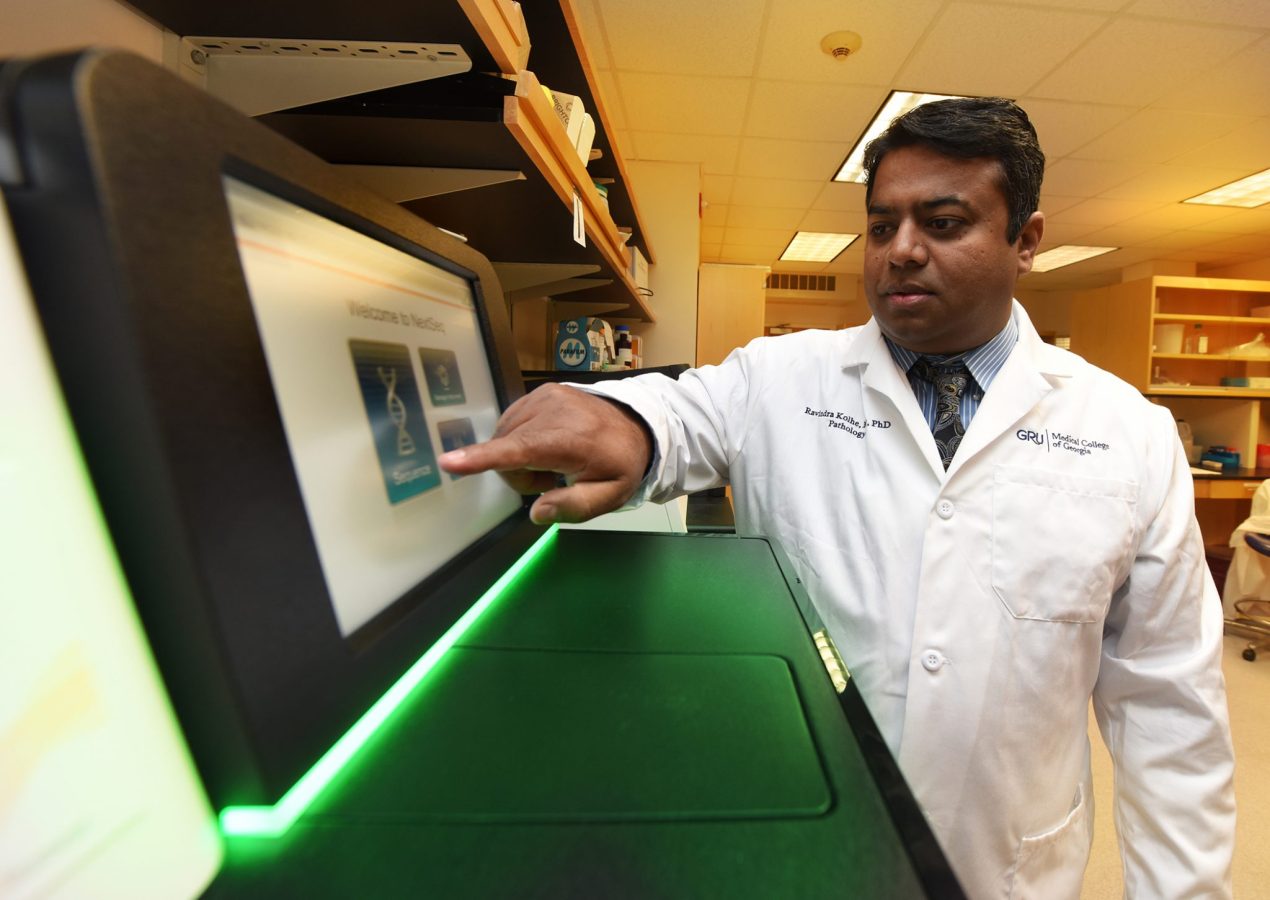

“We want to help people who are not responding to treatment and are dying very soon after their diagnosis,” said Dr. Ravindra Kolhe, breast and molecular pathologist and director of the Georgia Esoteric & Molecular Labs LLC in the Department of Pathology at the Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University.

A review of 40 patients with acute myeloid leukemia, or AML, found increased IDO expression in the bone marrow biopsy, performed to diagnose their disease, correlated with lower overall survival rates and early mortality.

It also indicates that IDO expression should routinely be measured when the diagnostic bone marrow biopsy is performed, Kolhe says.

An early phase clinical study already is underway to begin to explore the IDO inhibitor’s clinical potential in these patients. Sites include the Georgia Cancer Center as well as Johns Hopkins University and the University of Maryland Schools of Medicine, both in Baltimore. NewLinks Genetics Corp., a biopharmaceutical company based in Ames, Iowa that produces the inhibitor Indoximod, is funding the study.

“We wanted to look at what makes this leukemia so aggressive that initial induction chemotherapy is not working,” Kolhe says. “Early relapse tends to predict early mortality in these patients and one of the things we looked at was IDO,” says the study’s corresponding author.

While everyone has the IDO gene, it’s the cancer cells in this scenario that activate the disabler of the immune response that is also used by the fetus and solid tumors, he says.

Stem cells in the bone marrow are supposed to mature into a variety of cells that enable our blood and immune system function. Instead in AML, stem cells get stuck in an in-between, undifferentiated state called blasts.

“It’s very normal to go to the blast step, providing it matures from there,” Kolhe says. “In leukemia, stem cells get limboed in the blast state so you don’t get any maturation. That means there are low platelets so you get clotting problems, you have low neutrophils so you have infections, you have less red blood cells so you get anemic,” he says.

In fact, bleeding is a major cause of death for patients and often, significant gum bleeding is the first indicator.

The MCG researcher found one thing the blasts are producing is IDO.

“The patients who died at six months had a high expression of IDO while the blasts produced relatively little IDO in the patients who lived five years or more,” Kolhe says.

“Most of the time, we don’t know why patients are not responding to chemotherapy,” he says. But when the researchers adjusted for other risk factors for AML, like increased age and severe anemia, IDO levels were a standout.

“Right now we know it’s high in patients who die at six months and we show that it’s an independent indicator if you adjust for other known variables,” Kolhe says.

Next questions include whether high IDO directly affects resistance to chemotherapy, which occurs in patients who do not survive.

An MCG research team led by Dr. David Munn, pediatric hematologist/oncologist, and Dr. Andrew Mellor, immunologist, reported in 1998 in the journal Science that during pregnancy, cells in the placenta trigger an isolated suppression of the mother’s immune system so it won’t reject the genetically foreign fetus. They showed that IDO locally disables the mother’s immune system by degrading tryptophan, an amino acid essential to survival of T cells, orchestrators of the immune system’s response.

Later work would show that tumors – and leukemia – also use IDO to hide from the immune response. Conversely, some organ transplant patients who inexplicably express higher levels of IDO, have lower rejection rates of their new organ.

Kolhe, who completed his pathology residency at MCG and AU Health in 2012, got interested in IDO as at least one explanation for very different patient outcomes from the same treatments for the same disease.

Most patients with AML are at least age 45 at the time of diagnosis and it’s slightly more common in men than women, according to the American Cancer Society. Induction therapy is given to get the patient into remission, and is typically followed by more chemotherapy to help ensure it stays dormant. Some patients may also receive a stem cell transplant.

The published research was funded by a grant to Kolhe from the MCG Foundation. He is currently pursuing National Institutes of Health funding for further studies.

Clinical trials of an IDO inhibitor already are underway in other cancers, including a study in children with brain tumors, led by Dr. Theodore Johnson, pediatric hematologist/oncologist and 2004 MD/PhD graduate of MCG, at the Georgia Cancer Center and Children’s Hospital of Georgia.

Augusta University

Augusta University