When the COVID pandemic began in 2020, Dr. Amado Alejandro Báez, vice chair of operational medicine and director of the Center of Operational Medicine at the Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University, was tasked initially with developing AU Health’s ICU COVID surge program.

Báez, who is a professor of emergency medicine and epidemiology at MCG, serves in many roles at Augusta University. He is also a co-director of the Master of Clinical and Translational Science program, advisor for the FBI Augusta and Atlanta offices, chief medical advisor for the Georgia Bureau of Investigation and a faculty member in the Master of Arts in Intelligence and Security Studies program at Augusta University. He is all about creating interdisciplinary collaborations to improve public health.

In March 2020, Báez, who was born and raised in the Dominican Republic, received an unexpected call from the president of the Dominican Republic, asking him to serve as his lead for COVID preparedness and response.

After Báez consulted with Augusta University leadership, as well as the U.S. Department of State, the Dominican Republic president issued a decree and appointed Báez senior public health advisor and CEO for the presidential COVID taskforce. Since 2021, he has served as the director of health diplomacy for the Dominican Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

“We created an innovative, and now recognized by various international organizations, public value model to be reproduced locally at the provincial and municipal level,” Báez said. “We did a lot of good and worked with many great individuals. To this date, the Dominican Republic COVID data is much superior to many more developed countries. All probably directly related to a comprehensive test, trace, treat and isolate strategy as well as the development of local communities for public-private partnerships.”

To generate trust and show effectiveness only two weeks after being appointed, Báez was able to implement a pilot “public-value crisis model” in the province of Duarte that changed the trajectory of the COVID pandemic in the Dominican Republic.

“We utilized technology to develop telemedicine solutions, home health visiting teams, dedicated isolation hotels and optimized testing platforms,” Báez said. “At the same time, we created a dedicated COVID-19 hospital circuit with thousands of additional hospital and ICU beds.”

Combating views on ‘fake news’

But, much like in the United States, Báez became aware of a large segment of citizens in the Dominican Republic who did not trust the information they were receiving about COVID-19.

“One of the things that I thought was interesting was to approach epidemiological data with full transparency and objectivity because people needed to get properly informed,” Báez said. “And this was my first big government opportunity in the beginning of the pandemic. So, we thought, how can we address information issues more objectively? Especially since, in 2020, there was an epidemic and a presidential election year in the Dominican Republic. Therefore, politicizing COVID and vilifying actions and calling the information ‘fake news’ was a big challenge.”

In the spring of 2020, Báez came up with the idea of intelligence fusion centers to effectively communicate epidemiological information about COVID in the Dominican Republic.

“Because of my work with law enforcement and security services, I had worked in the past with intelligence fusion centers,” Báez said, explaining that these centers are a collaborative effort of two or more agencies that provide resources, expertise and information with the goal of maximizing their ability to detect, prevent, investigate and respond to threatening activities. “These are centers that were built after Sept. 11, 2001, in an effort to improve communication sharing between intelligence agencies.

“These centers make sure that local law enforcement is informing state law enforcement, who is informing federal law enforcement,” he added. “Basically, these centers make sure that everybody across the board that will deal with any major national security incident will have the proper information-sharing channels.”

Báez had also worked with graduates of the Epidemic Intelligence Service, a two-year post-doctoral training program offered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, to help promote effective public health information.

“I felt that doing an epidemiological intelligence fusion center in the Dominican Republic was the right way to go and the president supported that idea. He gave us access to a large military cyber intelligence center, which was the intel fusion center,” Báez said. “Strategically, we said, ‘This is a military facility, so we can understand the military perspective of creating intelligence products, but we also need the Ministry of Health. We need the Pan American Health Organization. We need the CDC.’

“The idea was that, by creating this center where private, public, military, academic folks and international organizations like the CDC and Pan American Health Organization could come together, we can all look at the same data from different angles.”

Using this epidemiological intelligence fusion center, the group was able to quickly identify the province of Duarte as a hotspot for COVID, ultimately changing the trajectory of the COVID pandemic in the Dominican Republic.

“Within 13 hours, we developed our first operation out of information intelligence products that we developed during our first meeting at the intel fusion center,” he said. “So, it became evident that it was a good effort.”

The center also had a social media analyst who followed information being posted about COVID on social media.

“She felt that there was about more than a 50% level of distrust on the data reported by the Ministry of Health,” he said. “A lot of people said, ‘No, this is not real. This is fake news.’ Similar to what happened in the U.S.”

Báez decided he would begin basing his reports on data provided by the CDC and the Pan American Health Organization.

“I began quoting specifically from the CDC and PAHO to let people know that, objectively, this is not the Dominican government reporting information,” Báez said. “This is the assessment of international organizations.”

Sharing the success

While working in the Dominican Republic, Báez stayed in close contact with Dr. Craig Albert, director of the Master of Arts in Intelligence and Security Studies program at Augusta University.

“We had this good experience in the Dominican Republic and we started wondering, ‘How do we share it? How do we let other people know?’” Báez said, adding that he and Albert, along with graduate student Joshua Rutland, had previously published a paper called “Human security as biosecurity: Reconceptualizing national security threats in the time of COVID-19.”

“We thought this was a logical second paper, so we decided, ‘Let’s write a case study on this experience and let other people know,’” he said.

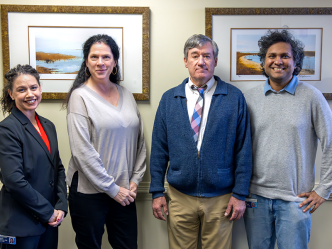

Albert teamed up with Báez, Rutland and Drs. Lance Hunter and John Heslen to write a new publication called “Epidemiological intelligence fusion centers: health security and COVID-19 in the Dominican Republic,” which was recently published in the Journal of Intelligence and National Security.

“This paper was a logical extension of the first paper because the main question for that first one was ‘Can an infectious disease really be a threat to national security?’” Albert said. “And if you look at this country that was shut down, clearly, that’s probably a threat to national security.”

Especially after studying the social media trends, Albert said the national security threat became more evident.

“What I was hearing from social media chatter and social media intelligence was Al-Qaeda and ISIS were looking at how they can possibly revamp their bioterrorism and biochemical attack plans to hit the United States because of the impact of COVID,” Albert said. “Basically, they were saying, ‘If this disease can shut them down, we can shut them down.’”

The focus of their latest publication was to show how nations can contain, prevent and mitigate infectious diseases and stop the spread of “fake news,” Albert said.

“So many people call fake news the other party’s view. Both sides call whatever they disagree with fake news. And that’s such a terrible thing for politics because there is an actual thing as propaganda, and when it affects your health and the national security apparatus, it’s horrible to mislabel it as something like fake news,” Albert said. “Therefore, the idea of this paper was based on the Dominican Republic’s experience, which is huge because you usually think of the United States as leading the way or a major power leading in this field. But here you have the Dominican Republic, under Dr. Báez, leading this intelligence fusion center.”

Preventing spread of future diseases

Through the intel fusion center, Báez’s team was able to collect information on where COVID was progressing and they were able to go out into the field and stop the spread, Albert said.

“In our policy recommendations, we show how these intel fusion centers can be applied and adapted, especially in the United States, so we no longer have to deal with inadequate emergency response to, not just COVID, but any infectious disease,” Albert said. “For example, we have an intel fusion center downtown at the Georgia Cyber Center, but, as far as we know, it’s not doing any epidemiological intelligence collection. But what if they did start doing that?

“They could trace monkeypox. They could understand how it is circulating and where are the hotspots,” Albert added. “You can incorporate social media analysis into these fusion centers so that when people say, ‘I have monkeypox,’ you can analyze it and make sure that it’s not traceable to a person. Cybersecurity technicians can see, where is the account registered and say, ‘OK, this is happening in Augusta, so we know a monkeypox outbreak is likely in Augusta.’”

That kind of information can help emergency departments and hospitals better prepare for potential outbreaks of infectious diseases, Albert said.

Albert was also pleased that their latest paper was published by the prestigious Journal of Intelligence and National Security.

“This is one of the most highly respected intelligence journals out there,” Albert said. “It is well circulated within the United States, as well as the National Security Council and even the White House. I mean, this is going to be a piece that hopefully President Biden is going to read and think, ‘Maybe we should create more epidemiological intelligence fusion centers based on the Dominican model.’”

In addition, Báez and Albert also aim for this paper to help shed light on a new graduate certificate program on public health intelligence that Augusta University is currently developing. This new certificate is expected to be launched in 2023.

This spring, the Master of Arts in Intelligence and Security Studies program will be offering a class in medical intelligence, Albert said.

“Here we have the intelligence and security field interacting with public health, interacting with MCG, creating this collaborative paper that led to the creation of this new class,” Albert said. “Once we got that class established, we saw the momentum for this collaboration and decided to create an entire certificate based on this field because people need to understand that, COVID-24 is going to happen and COVID-26 is going to happen.

“COVID isn’t stopping. Therefore, the idea is to start creating shared information between public health individuals and intelligence individuals, so we can all understand how it spreads and how to prevent it.”

Augusta University

Augusta University