Angela Stroman made her parents promise her they would go directly to Augusta University Health’s Emergency Room with any respiratory concerns during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In September 2020, Gonzalo “Kiko” Castro started feeling unwell, and with the encouragement of Stroman and her brother, Lee Castro, a paramedic in New York City, Kiko Castro went to the hospital.

Stroman, a registered nurse who works in the Division of Infectious Diseases at the Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University, said she had been working in an outpatient setting and had not had much interaction with COVID patients. If they were symptomatic or had a recent known exposure, they were diverted for COVID-19 testing prior to coming to the clinic.

“My knowledge of the very serious impact COVID-19 was having in our community came from colleagues and classmates that had been going full speed since the spring of 2020,” Stroman said.

Stroman also said her brother’s experiences had a huge part in her family’s reaction to any symptoms their father had.

“(Lee) had already been seeing the very worst of it firsthand … We talked regularly while he was going through it all, and every day he had another gut-wrenching story about arriving to a call where the patient was already deceased,” Stroman said. “Since most cases are relatively mild, we hoped that would be our parents’ case too … both of my parents had COVID at the same time, although my mom was feeling better within a couple of days.”

After initially being sent home with oxygen, Kiko Castro, 67, was still experiencing shortness of breath.

“She took me back to the emergency (room) and that’s the last thing I remember, leaving the house and getting there until I think it was six weeks after,” said Castro, of North Augusta, South Carolina.

Castro would spend the next 10 weeks at AUMC on a ventilator. He doesn’t remember anything more than the initial check-in and when he woke up, he thought he had only been there for a few days.

Stroman said she and her mother, Julie Ann Castro, a phlebotomist at AUMC, experienced emotions that were surreal. Her only reassurance came from the fact that her infectious disease colleagues were keeping an eye on him.

“After we took my dad to the ER, I got a call from Michael, a nurse in the MICU. He told me that my dad had been intubated and my heart just sank. I knew that with COVID-19 there were still so many unknowns and that many people never make it off the ventilator,” Stroman said. “My (colleagues) are some of the smartest, most amazing humans I know, and I knew they would do whatever they could to get him home.”

Rollercoaster of emotions

Castro spent 69 days in the medical intensive care unit and 17 in an intermediate care unit. He was later told he almost died twice, but the thought of that happening didn’t scare him because of his faith.

“I wasn’t scared at all because, you know, I’m ready,” Castro said. “I’m a Christian. It’s going to happen one day anyways, whether we’re ready or not. Really, I was never scared because I knew I was in good hands there because of the way they treated me and the way they supported my family. Great support. It means a lot.”

The family was finally able to see him three weeks later but a level of uncertainty clouded the visit.

“I was excited at first, but then it hit me that typically visitors are only allowed on that side if the patient is not expected to live for more than 24 hours, so I asked if that was the case,” Stroman said. “The nurse hesitated but said, ‘I don’t think that’s where we’re at at this point. We just know it’s been a long time since you’ve seen him.’ … On one hand I was glad I wasn’t there ‘to say goodbye.’

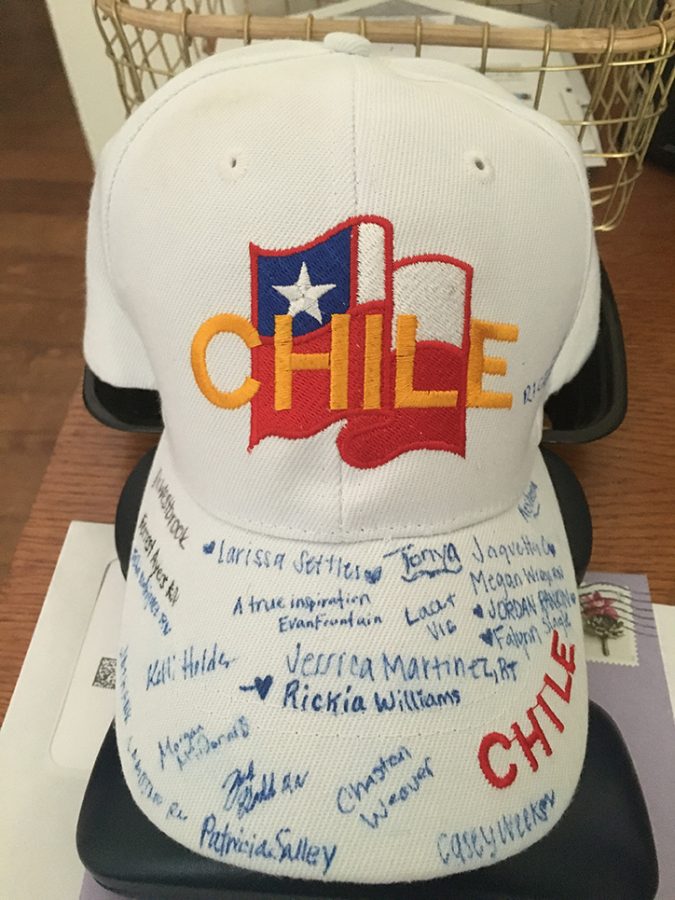

“My mom and I went in with nothing but words of love and encouragement. We held his hands, listed out all the people who love him and are thinking about him and just assured him that we were all with him in spirit. We also brought in music. I set up an iPad to play all of my dad’s favorite orchestral music. It pretty much stayed on 24/7 until we were able to see him again weeks later.

“Obviously the care team and medications made the biggest difference in his turnaround but I think there were several little things (like the music) that made a significant difference, too.”

By her own account, Stroman said this was “definitely the lowest point during our journey. My dad didn’t look like himself.”

Angels looking over him

As the days passed by, Castro started to get better. Stroman said she “could see the determination on his face. He was not about to give up.”

There was talk he’d be on the ventilator for another month but five days later, he was off of it — on his birthday, no less. In all, he endured four weeks of intubation, 10½ weeks on a ventilator, 13 weeks without the ability to speak and nearly 14 without the ability and strength to move.

“He worked tirelessly during rehab at Doctors Hospital, too. At this point (the family) just became cheerleaders,” Stroman said.

For Stroman and her family, the time her father spent in the hospital was the “longest rollercoaster of our lives.” They weren’t able to see him the first three weeks he was in the hospital. They celebrated the smallest of wins, and dealt with the setbacks.

“We just held on to every glimpse of hope we got,” Stroman said.

Stroman and her family are grateful for the colleagues who took care of her dad. She said being surrounded by so much death, at times it can seem that their efforts can often feel futile.

“We are so thankful to them for seeing my father as more than a lost cause. I need them to know that what they do matters,” she said. “We may not remember every name but we remember their voices, their spirits, and that they were there with us every step of the way.”

“Angels” — that’s how Castro referred to his team of doctors and nurses that took care of him during his time in the hospital. They all were encouraging and positive through the good and the bad.

“You can’t put a price on that (care),” Castro said. “That’s why I call them my angels.”

There are not enough words for Stroman to describe how much everyone’s hard work in taking care of her father means to the family.

“If the docs hadn’t already called me to consent for a procedure, I called every shift for an update. They were all so gracious … we hung on their every word,” she said. “I still remember nurse Maggie telling me, ‘He’s holding steady.’ That filled our tanks until nurse Crystal said, ‘He did pretty good last night.’

“The ICU can be such an emotionally heavy place to work, but you would never know it by the way they conduct themselves,” Stroman added. “Everyone from the respiratory therapists, the housekeepers, the nurses, the PCTs, the chaplains — each came and went with a positive word and a smile on their face, finding any way they could to help keep my dad comfortable. We will never know the personal sacrifices they’ve made to be so present, we just know that they took care of us. No one wants to find themselves in this position, but these are the people you want looking out for you if you do.”

Protecting the community

Castro has continued to exercise since getting out of the hospital. He was using a walker in early January to get around but now he’s walking three miles a day with no assistance.

Stroman said when it came time to get vaccinated, her dad looked proud.

“He had survived and was ready to do his part in protecting his community,” she said.

The family is encouraging everyone to listen to the medical experts and get a COVID-19 vaccine.

“Get your information from reliable resources like the CDC; talk with health care providers you trust … ask an ICU nurse,” Stroman said. “Getting vaccinated is a personal decision but it’s one that affects the health of our community as a whole. My heart breaks at the thought of anyone going through what my dad went through unnecessarily. Don’t take your ability to breathe for granted. People are dying before they have their opportunity to get vaccinated. Do it for them, do it for the people you love, do it to show yourself love.”

Read more about Kiko Castro’s battle against COVID-19 from WJBF, WRDW, The Aiken Standard and The Augusta Chronicle.

Augusta University

Augusta University