One of the most used phrases heard in today’s workforce is work-life balance. Ever since the COVID-19 pandemic, many have been focusing on just that. The phrase isn’t new, but has come into the spotlight lately, especially with burnout becoming more prevalent in the workforce.

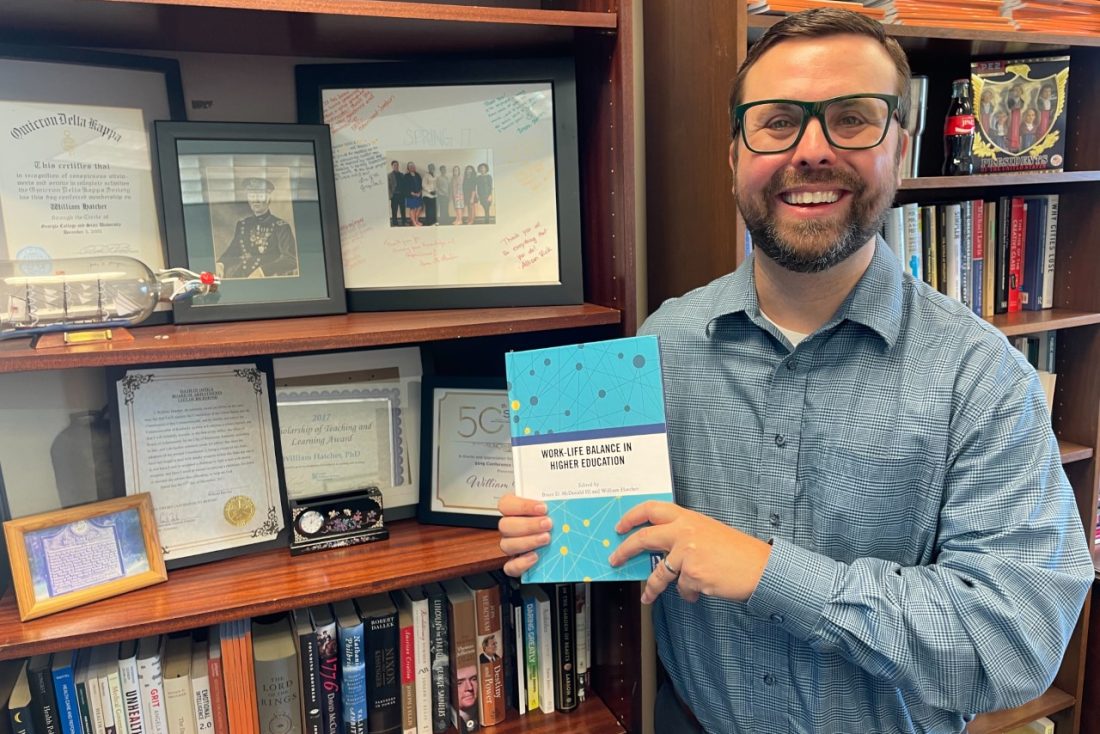

William Hatcher, PhD, chair of the Department of Social Sciences in Pampin College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences, has co-authored a book looking at this topic called Work-Life Balance in Higher Education.

The book is a collection of essays that have been published in the Journal of Public Affairs Education and Hatcher said there was a push from the publisher for additional content aimed at a broader audience.

While it may focus on balancing a personal life and a career in higher education, his book also includes valuable information for anybody in the workforce.

“One of the chapters that we talked about was our experience of interviewing top people in the field of public administration,” said Hatcher. “Many times they talked about how they got where they are because they didn’t have a work-life balance. Sometimes you can hear it from a standpoint of maybe I should have done things differently.”

Hatcher added that it’s difficult, if not impossible, to have a true work-life balance. Sometimes a person has to focus more on work, other times more on life, thus the difficulty in finding the balance that is so desired.

“The really good employees are the ones that can self-reflect and say this is where I’m the most effective. This is where I’m in the best place for being happy. And if I’m happy, I’m better at that job and I can balance everything with my life and have a life outside of work.”

William Hatcher, PhD

Burnout and work-life balance go hand in hand. Through his research, Hatcher said burnout comes from not having a sense of control in your job. Managing control is a big obstacle.

“Having that flexibility in your work schedule allows you to have that sense of control. It matters a lot when it comes to fighting burnout. Giving employees more control and having more flexibility in their schedule, if it’s possible, combats that,” said Hatcher.

He added one challenge to finding balance is that workers are often looking to get ahead. Part of our DNA is to strive for what’s next and look for advancement. While that can be rewarding financially, it may come at a price personally.

“The really good employees are the ones that can self-reflect and say this is where I’m the most effective. This is where I’m in the best place for being happy. And if I’m happy, I’m better at that job and I can balance everything with my life and have a life outside of work.”

Though burnout in the workforce has been growing for the past few decades, going through the COVID-19 pandemic brought to light to what life means outside of work for many people. It also allowed companies the chance to see how people can work efficiently outside of the office.

“Today with knowledge-based work that so many of us do, 9-5 workdays can hurt. You may put in more hours, but you’re not putting in productive hours. I think the pandemic focused that for a lot of companies. People can be more productive with teleworking and remote working,” added Hatcher.

When putting the book together, one aspect that stuck out to Hatcher was the chapter on graduate students. It got him thinking differently about the health of students and what we may take for granted. Many are currently working one or two jobs and if he’s more flexible and compassionate about that, they will be better students, he said.

“The thing about graduate students and why it’s important for faculty members to respect their work-life balance is because when you’re their advisor, mentor, dissertation advisor or thesis advisor, you have so much control over their lives. When they lose that control, that can lead them to have feelings of burnout, having struggles with mental health, and not feeling as though they have a balance between all their parts of their lives.”

Augusta University

Augusta University