Had Ken Griffey, Sr. never been part of baseball’s fabled Big Red Machine, had he not been part of three World Series championships or won the All Star MVP award, he believes he still would be talking to people about prostate cancer.

That’s just the way he was raised.

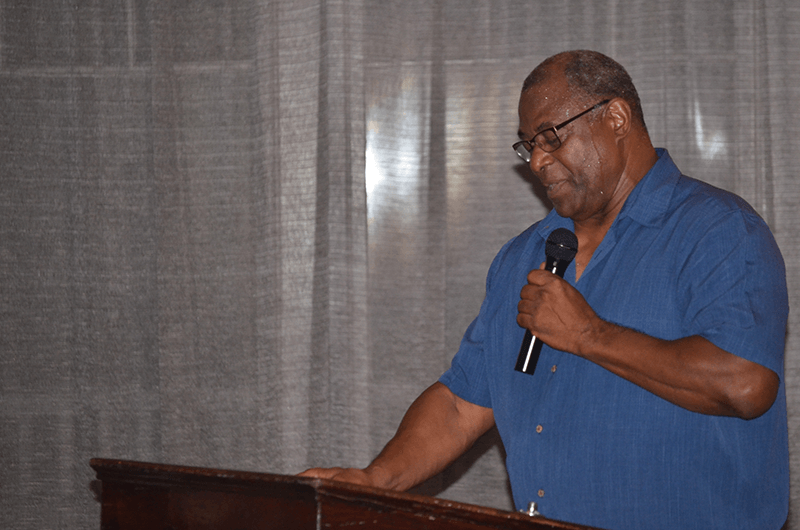

Griffey, who spoke last week at the Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University’s 43rd Annual Rinker-Witherington Urologic Society meeting at the Partridge Inn, said the idea of getting regular prostate checks predated his routine baseball physicals by several years.

“I was lucky,” he said. “My mother talked to me. She had lost four brothers to prostate cancer so she wanted all of us, me and my brothers, to know.”

It was those warnings, he said, that inspired his regular checks – checks that, ten years ago, revealed his own prostate cancer.

“They caught it early, very early,” he said. “I didn’t do chemotherapy or radiation – just surgery. But I do think it was genetic. In fact, my brother just had the same surgery.”

He said the most surprising aspect of his own diagnosis was how little people who shared the experience talk about it. He said once the press announced he had prostate cancer his friends, many of whom he had know for years, came forward and said they had gone through the same thing.

“Nobody talks,” he said. “And that is the worst problem. Especially the men themselves.”

He said there are a lot of reasons men don’t talk about prostate cancer or, more significantly, get tested on a regular basis. Fear, pride, denial – all are contributing factors. It’s a code of silence Griffey intends to break. His mission is to make men feel more comfortable with the idea of talking about what is a very common, and often very treatable, cancer. Over the past year, he has teamed up with Bayer and his son, Baseball Hall of Fame member Ken Griffey, Jr., to talk about the recognizing the symptoms of advancing prostate cancer. He said he had spoken to his children about the inherent risks just as his mother had spoken to him. He said the next generation is getting the message as well.

“My youngest grandson is nine year old and he will tell you,” he said with a laugh. “He will tell you don’t fear the finger.”

Augusta University

Augusta University