Fentanyl has become one of the leading causes of death in the United States.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently found that, of the estimated 107,543 drug overdose deaths in this country during 2023, approximately 74,702 were a result of fentanyl.

It was responsible for one-third of deaths among Americans ages 25 to 34 in 2022, according to the CDC.

Fentanyl is an incredibly potent synthetic opioid, and, much like heroin and other opioids, it can be highly addictive. One gram of fentanyl is estimated to be at least 50 times as powerful as pure heroin, according to the United States Drug Enforcement Administration.

But one Augusta University professor is making strides to battle the impact of this powerful drug on the nation.

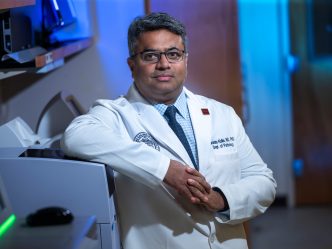

“Fentanyl addiction is one of the worst. It’s more addictive than heroin,” said Guido Verbeck, PhD, chair of the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry in the College of Science and Mathematics at Augusta University. “I never thought those words would come out of my mouth that anything was more addictive than heroin, but it is. Fentanyl has to be stopped. It has to be stopped now.”

Verbeck has developed technology that would make detecting fentanyl much easier and safer for law enforcement officers, who could overdose just through skin contact with the powerful drug at crime scenes and border crossings.

“Fentanyl addiction is one of the worst. It’s more addictive than heroin. I never thought those words would come out of my mouth that anything was more addictive than heroin, but it is. Fentanyl has to be stopped. It has to be stopped now.”

Guido Verbeck, PhD, chair of the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry in the College of Science and Mathematics at Augusta University

During a recent meeting of the Statewide Opioid Task Force held at Augusta University, which was headed by Georgia Attorney General Chris Carr, members of state law enforcement, public health officials and researchers discussed the dangers of this potent opioid.

“Last year alone, more than 107,000 people in the United States died of a drug overdose, and fentanyl was involved in nearly 70% of those deaths,” Carr said. “For perspective, that’s more than two times the number of people who died in a car accident in 2023.”

Finding a proactive solution

Despite the best efforts of statewide law enforcement agencies, Georgia has not been immune from this growing national crisis, Carr said.

“In 2022, there were nearly 2,000 opioid-involved overdose deaths in our state,” he said. “That’s nearly 2,000 family members, friends, coworkers and neighbors who lost their lives to this crisis in one year alone. And it represents a more than 300% increase from 2010. This is a mental health issue, a public safety issue and, most of all, a human issue.”

“This is the kind of research that has the potential to save lives. I’m very proud that this work is happening here in Georgia.”

Georgia Attorney General Chris Carr

Carr said he began the Statewide Opioid Task Force in 2017 to provide an infrastructure of communication between the public, private and nonprofit sectors to ultimately save lives.

“With our gang prosecution unit, we’re going after those who are trafficking fentanyl and other dangerous and deadly drugs in our communities, including right here in Augusta,” Carr said. “Last fall, we worked with the Richmond County Sheriff’s Office, the Columbia County Sheriff’s Office, the GBI, the Georgia Department of Public Safety, the FBI and other law enforcement partners to seize 15 pounds of fentanyl, enough to kill 3.5 million Georgians.”

“Now think about that for a minute. One operation, in one city, in one state, in one nation, enough to kill 3.5 million people,” he added. “That’s nearly one-third the size of the state of Georgia.”

As the director of the Laboratory of Imaging Mass Spectrometry at Augusta University, Verbeck introduced the Statewide Opioid Task Force to a possible solution to help fight fentanyl and other drugs throughout the country.

For more than a decade, Verbeck has been developing several inventions including portable mass spectrometry and chemical sensors, which can be used outside the lab to detect harmful chemicals in the air. These devices can be used to detect everything from explosive manufacturing and chemical weapon deployment to secret drug labs.

“We’re going after those who are trafficking fentanyl and other dangerous and deadly drugs in our communities, including right here in Augusta. Last fall, we worked with the Richmond County Sheriff’s Office, the Columbia County Sheriff’s Office, the GBI, the Georgia Department of Public Safety, the FBI and other law enforcement partners to seize 15 pounds of fentanyl, enough to kill 3.5 million Georgians.”

Georgia Attorney General Chris Carr

In fact, when Verbeck was a chemistry professor at the University of North Texas in 2015, he invented the world’s first “drug-sniffing” car with an advanced mass spectrometer that could detect trace amounts of illicit substances in the air and pinpoint the exact location of the source of the drugs on a map.

From a distance of a quarter of a mile, this drug-sniffing car with its portable mass spectrometry and chemical sensor could locate the source of the fumes from the drugs within a radius of 15 feet, Verbeck said.

“We took an old Ford Fusion hybrid sedan so we could run it in electric mode, and we would go to mapped areas, and it would find a (drug) cook lab a quarter mile away,” Verbeck said. “But you can see from 2015 to today that this technology is still not in our law enforcement’s hands. There’s still a lot of roadblocks to try to get this, especially between civil liberties and civil responsibility. So, my job is to break those barriers down and create these instruments and be proactive.”

Taking drug detection to the air

Verbeck has gone beyond creating a portable mass spectrometry and chemical sensor for vehicles.

He recently attached a mass spectrometer to an enormous drone he houses in his laboratory at Augusta University. One day, the drone could potentially be flown over neighborhoods by law enforcement to detect illicit drugs in the air.

If these chemicals are being released and detected in a public space, it becomes a public health hazard, Verbeck explained.

“If you’re making chemistry, and you’re doing something that is poisoning a public area, then that’s an environmental violation,” Verbeck said. “One of the beautiful things with this drone is you can stay in a public space. We built this device specifically for the protection of the public space and detecting where the chemical effluent stream is coming from. So, if you’re cooking in your house and the chemistry is coming into the public space, we can use environmental law, which is so much stricter right now than personal drug use law.”

“For example, there was a guy who was making methamphetamine at a campsite for himself, and it was a small batch amount, which would’ve been a misdemeanor,” he added. “However, he took all the leftover chemistry from the cook and poured it into the river. That ended up getting him 10 years in prison.”

“Right now, if you want to know what the drug is or what’s in the air, you have to grab a sample outside and bring it into the lab and then analyze it. The idea here is, could we reverse that? Could we make this instrument fieldable so that you don’t need to bring the sample to the lab?”

Guido Verbeck, PhD, chair of the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry

The science behind using a mass spectrometer would allow law enforcement to basically make drug detection devices portable or “fieldable,” Verbeck said.

“Right now, if you want to know what the drug is or what’s in the air, you have to grab a sample outside and bring it into the lab and then analyze it,” he said. “The idea here is, could we reverse that? Could we make this instrument fieldable so that you don’t need to bring the sample to the lab? It’s safer, especially when talking about drugs. If the DEA has an authorized seizure, they’ve got to take everything. But we’ve made the mass spec fieldable by taking the instrument and making it rugged, smaller and easy to use.”

Protecting the country’s borders

Through his research, Verbeck has received approximately $5 million in external funding, 90 peer-reviewed publications, 15 awarded patents and 12 applications.

These kinds of devices could be a game-changer for law enforcement, especially for border patrol officers, Verbeck said.

“We’ve been working on a project looking at explosives and drugs that come across the border,” Verbeck said. “So, one of the missions in my group is not just to build the instrument, but to go to where the problem is, see the problem and then try to figure out how to implement the instrument to solve the problem.”

A mass spectrometer can monitor all of the chemicals used to produce drugs, Verbeck said. He explained that there are currently more than 250 different analogs of fentanyl with molecular structures closely similar to each other.

“Back in 2013, we had fentanyl. In 2015, we had three analogs of fentanyl. In 2023, we have 233 analogs of fentanyl, and today we have 266,” Verbeck said. “The problem is a lot of times law enforcement is not given the tools that they need to be proactive. We can only be reactive. And now we have an epidemic. But could we stop it? Is there a way to try to stop it at our borders and at our ports? I think we can.”

Currently, in Laredo, Texas, one out of every 11 shipping trucks is pulled over and tested in a tedious process, Verbeck said.

“We are creating a process now where everybody who crosses the border can be tested, and it is a two-minute process,” Verbeck said. “You can have a line of vehicles that are coming across the border and simply fly the drone over the line of cars. We went down to Laredo for two weeks analyzing cars, and we were able to detect cocaine in the little rubber bladder of a truck. We were able to detect methamphetamine in the gas tank of a Cadillac because our detector is oil and gas agnostic. So, for us, we’re asking, ‘What is the problem, and how can we solve it?’”

“In fiscal year 2024, GBI drug units and gang units seized more than $10 million worth of fentanyl, and over $160,000 worth of opioid pharmaceuticals. For the last two years, that was over a 500% increase in what we had been seeing.”

Chris Hosey, the director of the Georgia Bureau of Investigation

During the Statewide Opioid Task Force meeting held at Augusta University, Chris Hosey, the director of the Georgia Bureau of Investigation, said he was pleased to see public, private and nonprofit partners working to protect the future of Georgia because Atlanta is considered the major hub for narcotics, including opioids, coming into states east of the Mississippi River.

“With I-75 being a corridor to the North with Tennessee, Kentucky and Indiana and I-85 going to North Carolina, Virginia, the D.C. area and Maryland, Atlanta is still the major hub,” Hosey said. “And opioids are still the most prescribed and dispensed controlled substance in Georgia. We saw a fentanyl rise again for the sixth straight year, and we’re seeing it mixed with other drugs, including heroin, cocaine and counterfeit prescription pills.”

However, unlike other opioid drugs, fentanyl can be made entirely in a laboratory, Hosey said.

“We’re seeing the counterfeit pills being produced not only locally, but also smuggled into this country as well, coming from our borders through California, Texas, New Mexico and Arizona,” Hosey said. “But we’re also running across it through the ports, not just in Georgia, but around the country. We’ve also seen it through air delivery, FedEx and UPS, and then obviously by land, as well.”

“In fiscal year 2024, GBI drug units and gang units seized more than $10 million worth of fentanyl, and over $160,000 worth of opioid pharmaceuticals,” Hosey added. “For the last two years, that was over a 500% increase in what we had been seeing.”

Detecting dangerous chemicals to save lives

Verbeck is currently working on developing a small, wearable mass spectrometer that could warn law enforcement officers of dangerous chemicals nearby.

“Prior to 2015, if you saw something with white powder, you could touch it, you could test it, you could do whatever you wanted to process it,” Verbeck said. “Now, when you see a white powder in the back of the car, nobody wants to go anywhere near it. So, law enforcement’s hands are tied when trying to do their job. We need to put in their hands some way of being able to detect these chemicals and tell them exactly what it is before they bring it into the lab.”

“One of the missions in my group is not just to build the instrument, but to go to where the problem is, see the problem and then try to figure out how to implement the instrument to solve the problem.”

Guido Verbeck, PhD, chair of the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry

These portable mass spectrometers can also be used in a variety of ways to protect cities, hospitals and schools from dangerous chemical releases, he said.

“The main application that we really love for the drone is to protect firefighters and first responders,” Verbeck said. “Let’s say, an industrial fire occurs. The firefighters have to circumnavigate the building with the truck to assess it before they decide to fight it or not. The drone could completely replace that situation.”

Verbeck’s drone has the ability to stay airborne for 45 minutes and travel a distance of approximately 30 miles, he said.

“So, if a fire is called in, the drone can immediately take off and go to the location. It can circumnavigate the building. It can use infrared cameras so that you can see in the building and determine if there are people still there,” he said. “But it can also tell the firefighters what chemistry is burning in that building and whether or not they should enter. A drone can do all of that while the firetruck is en route. It’s a beautiful example to save lives.”

“We respond to our communities that are afflicted by this crisis, and most people often ask, ‘What can a fire department do as it relates to this?’ From Narcan distribution and training, data collection from our responses, public awareness campaigns, school and community programs and post overdose outreach, we are on the cusp.”

Augusta Fire Chief Antonio Burton

In the future, Verbeck hopes to possibly test the drone with the Augusta Fire Department over its training facility.

“Our first responders need help because fentanyl is very dangerous, and it’s starting to be homemade,” he said. “It was manufactured in other countries and shipped directly here, but those supply lines are starting to be interrupted. So, now it’s starting to move into people cooking it themselves, and that’s dangerous.”

Augusta Fire Chief Antonio Burton told the Statewide Opioid Task Force that the fire department is battling these kinds of challenges every day.

“We’re on the front lines of this crisis,” Burton said. “We respond to our communities that are afflicted by this crisis and most people often ask, ‘What can a fire department do as it relates to this?’ From Narcan distribution and training, data collection from our responses, public awareness campaigns, school and community programs and post overdose outreach, we are on the cusp.”

Burton said he wants to make sure his department has the tools to win this battle on opioids.

“We’re here in this fight,” Burton said. “Lives are literally at stake, and this is a fight that we have no choice but to win.”

Looking to the future

AU President Russell T. Keen said the research being conducted at Augusta University will have a definite impact on the fight against fentanyl.

“Research, collaboration and translating that into action is what’s going to get us out of this epidemic,” Keen told the Statewide Opioid Task Force. “We are proud to stand with you in this fight.”

Carr said he was glad to hear Verbeck’s presentation during the recent meeting of the Statewide Opioid Task Force held at Augusta University.

“This is the kind of research that has the potential to save lives,” Carr said. “I’m very proud that this work is happening here in Georgia.”

Verbeck said he is passionate about the research he is doing with his graduate students in the Laboratory of Imaging Mass Spectrometry at Augusta University.

“Augusta University is a fantastic mission for me,” Verbeck said. “First, just on the university side, was to bring the PhD program in chemistry here for Augusta University as it’s growing and emerging as an R1 university. But for my research, the main reason I came to Augusta University is for the clinical aspect.”

“Augusta University gives me access to be able to do those types of medical- and health-related applications, but at the same time continue to fight the war on fentanyl.”

Guido Verbeck, PhD, chair of the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry

Verbeck’s research into mass spectrometers and chemical instruments led him to develop the first FDA-approved breathalyzer for disease detection.

In addition, Verbeck received a grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation last year to create devices for detecting other diseases, such as malaria and tuberculosis, that can be installed outdoors in any environment. He was also named to the 2023 Class of Fellows for the National Academy of Inventors.

“Augusta University gives me access to be able to do those types of medical- and health-related applications, but at the same time continue to fight the war on fentanyl,” Verbeck said. “We want to help those fighting fentanyl on the front lines, stopping it before it even gets across the border by flying these drones and finding the supply lines. We have to be proactive in order to win this fight.”

Augusta University

Augusta University