Humble and soft-spoken are just a few words that come to mind when people describe Dr. Roscoe Williams. Now, 50-plus years after becoming the first African American in a professional position at Augusta University, Williams was honored Nov. 4, when the Jaguar Student Activities Center ballroom was named after him.

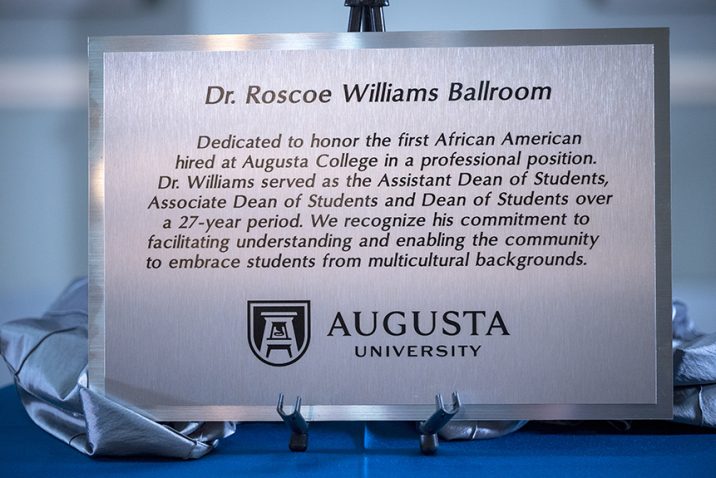

The ceremony featured Augusta University President Brooks A. Keel, PhD, unveiling a plaque that will hang outside the ballroom, letting everyone know some of the history behind Williams.

Many of his family members were present at the ceremony, as well as numerous past and present school officials and some students who were enrolled while he served as dean.

“It would be very difficult to explain to you how happy I am. It kind of completes the story, the journey,” said Williams. “When I came in 1970, never did I think this day would happen or this would occur, that somebody would be so gracious as to recognize me and I will be in turn indebted to them for the gesture.”

Williams was the first African American to serve in a professional position at what was then Augusta College. He would retire 27 years later as dean of students, having impacted the lives of thousands of students. He’s quick to deflect some the attention away from him.

“I really don’t like boasting about anything, because you really don’t get to any place in life without the help of other people,” said Williams.

While Williams is credited with helping grow the minority population at the university, he was an advocate for all students and believed in empowering them.

“I like to believe that I served as a role model for a lot of students. Beyond that, just the presence of more people of color. I thought in time it helped because we graduated more and more people of color and to that extent, that was good,” added Williams.

Cedric Johnson served on the taskforce that looked into African American history at Augusta University and said, without question, Williams was the one person who stood out above everyone else.

“The way he stood out was number one, he was courageous in taking on a task that he knew would make him sometimes uncomfortable. But he was determined to do the best that he could under the circumstances,” said Johnson.

Williams was hired during a pivotal time in the college’s history, as well as the history of Augusta. In 1970, the city saw racial riots, and Williams would join and eventually become chairman of a human relations commission that was formed in response to them.

Some called for him to be fired from the college because of that work.

“It was recommended that maybe President [George A.] Christenberry fire me for the stances that I took as chair, which were no more than asking for equity and equality. I was blessed that Dr. Christenberry served on the human relations commission himself, so he knew what it was all about.

“It came out in the paper one Sunday that he should fire me, so I got to work that Monday morning and he came by my office. He was smoking his pipe and said, ‘How are you doing today?’ and I said fine, and we talked a while and he said, ‘I just want you to know you don’t have to worry about anything. I know what you’re doing, I trust you.’ He said ‘I’m not listening to all that other stuff. I just want you to continue to do a good job here and at the commission,’” said Williams.

He still remains a fixture at the school. Following his days as dean, Williams served as clock operator for the basketball teams. He can still be found at Christenberry Fieldhouse on a routine basis, getting his workouts in or even taking photos during games, a hobby he had going back to his younger years.

During the ceremony, Keel reiterated the lasting legacy of Williams.

“His commitment to and passion for education greatly contributed to retention of graduation rates of African American students both at Augusta College and through the state of Georgia,” said Keel.

Augusta University

Augusta University