The Institute of Public and Preventive Health at Augusta University received a $1 million Health Resources and Services Administration Award to help those with opioid-use disorder.

More than 130 people die each day from opioid-related drug overdoses, according to the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA).

Here in Georgia, the total number of opioid-related overdose deaths increased by 245 percent from 2010 to 2017.

And some of the hardest hit areas are rural communities across the state, according to Dr. Aaron Johnson, director of the Institute of Public and Preventive Health at Augusta University.

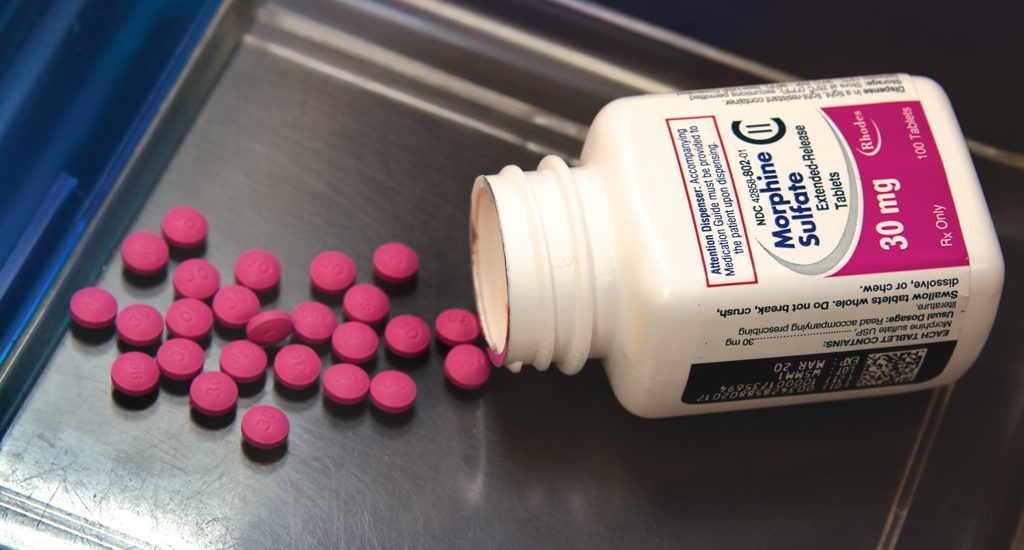

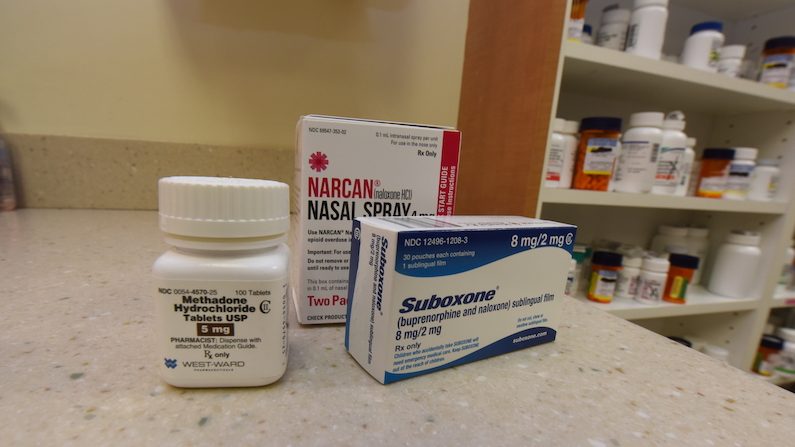

“We know that the standard of care for treating opioid-use disorder is medication-assisted treatment combined with behavioral therapy and there are really two medication options — methadone and buprenorphine,” Johnson said. “The problem is that neither option is widely available in our rural counties. Methadone treatment is highly regulated and largely confined to urban areas.”

For example, there is a program available in Augusta, but it may not be a convenient daily drive for those living in surrounding rural areas.

“With methadone, you essentially have to come in every morning to get your daily dose,” Johnson added, explaining that methadone is a medication that reduces withdrawal symptoms, allowing people with opioid-use disorder to function normally. “If you live 45 minutes away, you don’t want to drive 45 minutes to Augusta to get your daily dose of methadone and then drive 45 minutes back to work. That’s not feasible.”

To help address opioid-use disorders in rural communities, the Institute of Public and Preventive Health recently received a $1 million HRSA Award to implement and expand access to recovery and treatment options.

The Institute of Public and Preventive Health team, which consists of Johnson, Catherine Clary and Dr. Vahe Heboyan, will be teaming up with three Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) – Community Health Care Systems Inc.; East Georgia Healthcare Center; and TenderCare Clinic, Inc. – that have primary care clinics in the following 22 rural counties in Georgia: Baldwin, Glascock, Hancock, Jefferson, Warren, Wilkinson, Bulloch, Emanuel, Jefferson, Warren, Wilkinson, Jenkins, Tatnall, Treutlen, Greene, Johnson, Laurens, Taliaferro, Telfair, Washington, Appling, Candler, Montgomery, Toombs and Wayne.

Partnering to provide solutions

The Georgia Council on Substance Abuse and Dr. Paul Seale of Navicent Health in Macon, Georgia, are also joining the coalition on this three-year project, Johnson said.

“I think the Georgia Council on Substance Abuse, which is based out of Atlanta, is a great partner and I’m looking forward to seeing them take their expertise from what they’ve done in Atlanta and translate it into these 22 rural counties,” Johnson said. “They have established some recovery community organizations in the Atlanta area, but there are really not equivalent organizations in rural areas. So, I am excited to see how successful they are at getting those up and running in rural areas because I think that’s huge for people who are trying to be successful in their recovery.”

Seale is a family medicine physician in Macon who has also been a buprenorphine treatment provider for more than decade, Johnson said.

His primary role in the project will be to meet with physicians in rural areas and talk about the value of buprenorphine for those suffering from opioid-use disorder, Johnson said.

Unlike methadone, buprenorphine can be prescribed by community-based providers. They just have to complete a training to become a “waivered” provider, he said.

“There is still a fair amount of stigma attached to medication-assisted treatment and a lot of the physicians who are in family practice or in general practice are hesitant to become buprenorphine waivered because their perception is that they don’t want to become known as the place that treats ‘those people,’” Johnson said, “The reality is, ‘those people’ are already getting primary care services in the clinics. The providers just are not identifying and addressing what may be one of the major contributors to their health conditions.”

Seale will be able to explain to rural physicians that medications such as buprenorphine and Suboxone, which is buprenorphine and naloxone, in combination with counseling and behavioral therapies, provide a whole-person approach to the treatment of opioid dependency, Johnson said.

“I think there are 12 physicians who are currently waivered to prescribe buprenorphine within the 22 counties that we are working with,” Johnson said. “Hopefully, with this three-year project, we can make those medications more available.”

And providing those medications will not disrupt a physician’s practice, Johnson said.

“Some of the physicians are worried that their entire practice will become consumed with individuals who are there for buprenorphine, but that really doesn’t happen,” Johnson said. “In most cases, if you look at the physicians who have become waivered to prescribe buprenorphine, the patient limit for the first year is 35 patients. After that, you can go up to 100 patients and then there is a way to go up to 275 patients.

“But the majority of physicians who have become waivered to prescribe buprenorphine aren’t treating the full 35 patient limit,” Johnson added. “So, it is not like it overwhelms your practice when you become a buprenorphine provider.”

Fighting the stigma

In 2017, the same year President Donald Trump declared the opioid crisis a national public health emergency, a total of 1,043 people in Georgia died of drug overdoses attributed to opioids.

Catherine Clary, the director of Augusta University’s Center for Rural Health, explained the lack of medication-assisted treatment in rural counties put those citizens at an increased risk for overdose-related deaths.

“In urban settings, there might be more opioid use, but in rural settings, those with opioid-use disorder are more likely to overdose and more likely to die of an overdose,” Clary said. “And while there is a stigma attached to medication-assisted treatment, it has shown to be one of the best ways to help people. So, we will be working to fight that stigma.”

According to the Substance Abuse Research Alliance, 60 percent of the 55 counties in Georgia with drug overdose rates higher than the national average in 2014 were located in rural areas.

The same problem clearly exists in the 22 Georgia counties involved in this project, Johnson said.

Clary said this recent $1 million HRSA award will complement a previous five-year, $5 million grant Johnson received from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

The $5 million grant essentially funds a full-time licensed clinical social worker in seven Federally Qualified Health Centers that fall in a geographic triangle formed by Augusta, Macon and Savannah.

“We’re lucky because some elements of this program have already been in place,” Clary said. “We will expand these services into more of the rural counties in this area and add some prevention and recovery efforts to complement these services.”

Johnson also wants to train providers in these rural counties to implement Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) in their regular practice.

“When it comes to asking individuals about alcohol or drug use, it’s really not the question. It’s the way you ask the question,” Johnson said. “We work really hard with, not only the providers, but also the nursing staff and nursing assistants, so that they understand when you ask questions related to an individual’s alcohol or drug use, you have to ask it in a nonjudgmental way so that they feel comfortable sharing that information with you.”

Despite what some people may believe, most patients are willing to discuss their alcohol or drug use with their providers if asked in the proper manner, Johnson said.

“A lot of cases where patients have been defensive about responding to those questions is because of the way that they are asked,” Johnson said. “Along with talking to providers, we are developing some signage that they can put in their waiting rooms that says things like, ‘We ask because we care.’

“And it would have a sentence or two that would say, ‘We ask all of our patients about their alcohol and drug use because we are interested in having the healthiest patients.’”

The delivery of those kinds of questions is what’s most important, he said.

“The signage in the waiting rooms will sort of prime the patient before they ever go in to see the nurse,” Johnson said. “They will know that they are going to be asked these questions and the reason why.”

Training the next generation

Another critical aspect of this project is to train medical students in the use of naloxone, which is a spray or injection used to counteract overdoses.

For that component, the team will partner with Dr. Matthew Tews, associate dean at the Medical College of Georgia, and Nicole Winston, an assistant professor of pharmacology and toxicology.

“Training a medical student to administer naloxone is not difficult, but the education around substance-use disorders that accompanies that training is so critical,” Johnson said. “As a medical student, this is something you need to be concerned about and you need to integrate into your practice. Substance-use disorder is something they will regularly see and, with this training, they may even have an opportunity to save someone’s life.”

Over the past three years, Johnson has trained more than 1,000 Augusta University medical students to identify and address unhealthy alcohol and drug use in patients.

Medical students must be prepared to ask patients about their alcohol and drug use because there are a number of chronic conditions such as cancers, hypertension, liver disease, mental health conditions and obesity that can be directly linked to an individual’s alcohol and drug use patterns, Johnson said.

“When they sit down with their patients, they need to at least think about this patient’s chronic condition and how it may be linked to unhealthy alcohol or drug use,” Johnson said. “So, at least ask about it.”

Clary explained that the medical students trained by Tews and Winston will also be provided two doses of naloxone to carry with them during their rotations.

The purpose is to make sure the medical students are prepared for what they may encounter in the communities where they will be doing their clinical rotations, she said.

“That way, when they go out on their rotations as students, they will have naloxone with them and they can help in some of the rural areas,” Clary said. “Because we want to them to be trained and ready to help prevent overdose deaths.”

Augusta University

Augusta University