This story from late October finished last year as the second most popular story on Jagwire, coming up short only to a story about parking enforcement. It tells the story of Grandison Harris, a slave (and later an employee) who came to be known as the Resurrection Man…

The Night Doctor is in:

Nearly two hundred years ago, in a tiny cemetery on the outskirts of town, a splintering crack split the midnight calm like the firing of a mortar. It was a common warning, one well understood by both Augustans and their dead alike.

It meant the night doctor had returned.

On the ground before him lay the fragments of a coffin lid. Sheared away with almost surgical precision, the pieces were kept close, clustered in a pile beside him. They’d be easier to replace that way. Hanging his ax at his belt, he brushed them carefully aside before thrusting his hands into the waiting earth.

It was time for another extraction.

The operation was a simple one. Over the past eight years, he’d performed dozens just like it, all in the small hours of morning. Though the act still made him nervous, his hands didn’t shake quite as badly as they’d used to. In fact, for an unorthodox surgeon, his bedside manner was impeccable. None of his patients ever complained about the roughness of his hands or the pace at which he worked.

Moments later, he rose, finished. Out of its grave, a body rose with him.

Checking the name on the headstone against the one published in the Chronicle days before, the intruder nodded. He replaced the coffin lid, covered it well. Then, careful not to break anything valuable, he scooped the body into an old burlap sack and hefted it over his shoulder.

His name was Grandison Harris, and though the slaves of Augusta called him a ghost, a ghoul and a villain, the rest of Augusta had another name for him.

This is how he earned it.

Rise of the Resurrection Man:

In the mid-19th century, the United States found itself in a strange moral predicament.

Regardless of where they stood on the issue, most believed slavery would lead to war within the century, and the tensions were mounting.

Swept up in the fever of that oncoming civil war, though, many overlooked another important moral dilemma of the day: the dissection of cadavers.

As late as 1887, it was illegal in the state of Georgia to perform a dissection on a human body.

The lone exception to the law was the dissection of executed criminals, a practice viewed both as a public service and a deterrent to further crime. While helpful, the exception proved problematic for a very simple reason: Georgia, the state with the fifth highest total of executions, couldn’t produce enough bodies to fulfill even the needs of the Medical College of Georgia, which at the time consisted of just seven faculty and a few dozen students. Combine that with the faculty’s poor luck purchasing corpses from local families – an act which was, if questionable, still considered legal – and the little school’s troubles were plain to see.

It was a trying challenge: How could educators teach anatomy to a growing student population with a shortage of cadavers?

The answer, like the problem, was simple. They couldn’t.

So left with no other choice, the faculty considered their only other option: stealing bodies.

At the time, it seemed like a reasonable enough solution. All over the country, medical schools and hospitals were turning to grave robbing to fill a growing need for fresh specimens. Some saw it as a moral obligation. If the state and the community couldn’t provide cadavers fast enough for the needs of medical research, then it was up to medical researchers to carry on in spite of the law. The continuation of medical science, in their eyes, was a far more important cause.

But like so many other solutions of the day, this one, too, came with its own set of problems.

For one thing, seven local doctors couldn’t be caught digging up bodies. Their careers, not to mention their lives, would have been over if the police ever caught them. Worse, in an up-and-coming city like Augusta, the mere whiff of a body-snatching scandal would have been enough to run their families out of business as well.

The faculty needed a fallback plan, a piece of plausible deniability.

Faced with the understanding that what they were doing could very well mean the end of their careers, they made a decision that would shape their college’s future for half a century to come.

They bought, and later hired, a grave robber.

An Incomplete Picture:

Purchased in 1852 for $700 at a slave market in Charleston, 36-year-old Grandison Harris was jointly owned by all seven faculty members of the Medical College of Georgia. A common sight in the college’s lecture halls, the burly Gullah could often be seen attending classes and cleaning up after students as necessary, sometimes well into the evening.

His role was formally listed as “janitor and porter,” a task for which he was overly qualified. Capable of both reading and writing, his role as handyman seemed to many an oddity, if not an outright waste. But Harris had another title at the college. One not listed in the official ledger.

Resurrection Man.

Beyond that familiar moniker, however, very little is clear about Grandison Harris or the circumstances surrounding his “nightly mischief.”

In May of 2014, author Bess Lovejoy wrote an article for the Smithsonian detailing Harris’s grisly career titled “Meet Grandison Harris, the Grave Robber Enslaved (and then Employed) By the Georgia Medical College.” However, even that well-researched account leaves several important questions unanswered.

In it, Lovejoy claims that Harris was well-liked by the faculty and students of the old college. He was apparently a regular guest during anatomy lectures, there both to clean and to assist students with their dissections as necessary. That changed after the Civil War when Harris earned his freedom. Shortly after, he left the college to serve as a Reconstruction judge in Hamburg, S.C. – a ghost town formerly located across the 5th Street Bridge. While ambitious, Harris’s efforts to change his fate were eventually thwarted. The advent of Jim Crow laws, local and state laws enforcing segregation, eventually destroyed his position.

Left with no other option, he returned to the college, where he took a paid job as a porter. But things were never the same.

Lovejoy claimed that during his second stay with MCG, the students and faculty routinely ribbed Harris by calling him “Judge” – a snide remark intended to poke fun at what they considered an act of treason against the South.

But if Harris ever complained about either of his nicknames, there is no living record of it.

Despite his troubling duty and his uneasy relationship with his employers, he was never thought to be a pessimist. Nor, for that matter, was he a loner. An apparently very friendly man, he was a regular at several local bars, where he would sometimes park his cart between deliveries. After having been freed, he seemed inclined to throw large parties, to which only the most affluent free men among the community were invited. He had a family – a wife and a son – from whom he was separated following his purchase in 1852. After being purchased by the medical college faculty, they eventually joined him in Augusta, where his son, George, would later became his successor.

Though he served the college faithfully in his fathers’ absence, several historians agree that Harris the younger had neither the heart nor the stomach to follow in his father’s footsteps.

As time would later prove, living up to Grandison Harris’s legacy was a task too demanding – and far too ghastly – for his son to ever complete.

Folklore, fear and the furthering of medical research:

If Harris’s tenure as a judge left him distrusted by the students and faculty of the medical college, then his years of grave robbing left him outright feared by the city’s African American community.

Reportedly, after word of his actions spread through Augusta, riots formed to demand justice for the stolen dead. Those involved cited Harris’s repeated desecration of Cedar Grove cemetery and brought to light perhaps one of the eeriest details of the Resurrection Man’s grisly career, namely his knack for memorizing and perfectly recreating flower arrangements above graves.

But the loudest outcry didn’t come from those who knew their dead were missing.

The largest outpouring of grief came from those who didn’t know – who would never know – if their dead had been taken or not.

While no clear record remains of how the riots ended, one thing is certain: Neither Harris nor the Medical College of Georgia were ever charged with stealing bodies. The practice continued well after the Civil War.

The scenario was a common one in the South.

With no laws or rights to protect them and with no true authority to turn to, the bodies of slaves, and later the bodies of freed slaves, were the easiest targets for medical study. In fact, the continual theft of African American bodies eventually spawned its own folklore, rife with stories of medical-themed horror. Such stories often included references to “night doctors,” supernatural figures said to hunt down runaway slaves and dissect them alive. The practice ultimately fostered a culture of fear among African Americans, the implications of which, some say, still live on today.

Untouchable, frightfully powerful and known by most everyone in his community, Harris became something of a night doctor himself by the end of his life.

Whether or not the fact ever bothered him, we may never know.

To our knowledge, he never wrote about the issue, though he had the ability to do so. None of the guests at his parties ever recounted him having mentioned feeling troubled or having ever talked about what he did at all. For all intents and purposes, Grandison Harris’s thoughts on grave robbing are, and always will be, a mystery.

Those thoughts aside, however, there’s no denying that his efforts unquestionably furthered medical research.

And those efforts, it turns out, were quite substantial.

Known but to God:

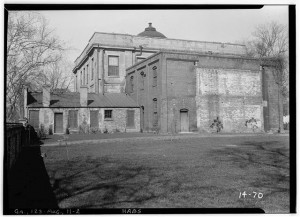

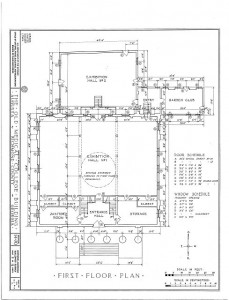

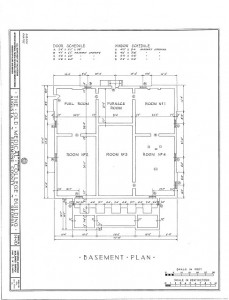

In the summer of 1989, a team of construction workers renovating the Old Medical College building discovered something unnerving in the structure’s worn out basement. Buried in a massive dirt pit, barely deeper than a grave, were thousands of human bones.

In all, according to Lovejoy, more than 10,000 individual bones were removed from the site of the old college building, the remnants of hundreds of dissected bodies. Many showed outward signs of study. Others still bore their specimen labels. But regardless of the wear and tear they’d sustained, it was clear where most had come from.

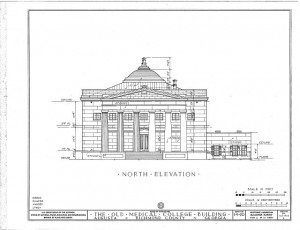

From 1835 to 1912, the impressive Greek revival style building on Telfair housed almost all of the Medical College of Georgia’s anatomy classes. During that time, multitudes of desperate grave robbers performed the same gruesome task, exhuming the corpses of slaves and former slaves from Cedar Grove and delivering them into the hands of anatomy professors.

Today, though, only one of those grave robbers is remembered.

In 1911, Harris died of heart failure at the age of 95. A former slave in the pre-Civil Rights era, he was buried somewhere very near, if not necessarily dear, to his heart. Many thought it fitting. After all, he already had an intimate, some would say obscene, knowledge of the place.

The flood of 1929 destroyed all records of burial locations in Cedar Grove. Where exactly Grandison Harris’s remains lie today is a mystery, but in 1998, a few hundred other residents joined him in interment.

Together, they lie buried in once mistreated earth, honored by a simple marker.

Etched on that marker’s face is a phrase which perfectly sums up the life and mind of Cedar Grove’s most infamous resident.

It reads, “Known but to God.”

Augusta University

Augusta University