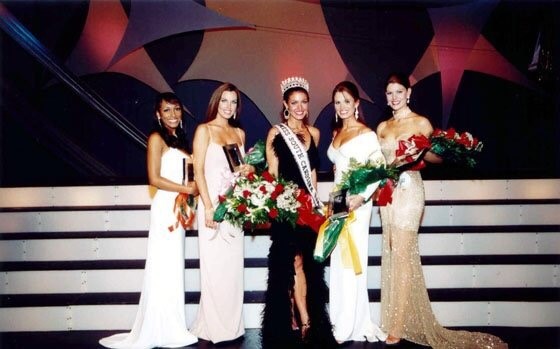

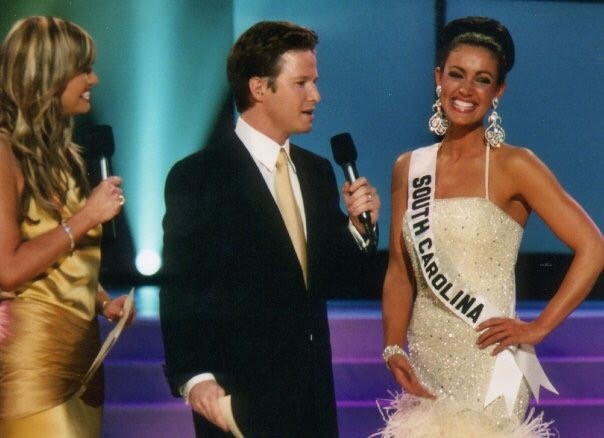

Fifteen years ago, Miss South Carolina USA was backstage at the Miss USA pageant in Hollywood, a finalist to win the big crown.

It was all so hard to believe.

“I remember thinking, ‘My gosh … what? Are you sure I’m here?,'” she recalled. “It was incredibly humbling that I got that far.”

They called fourth runner up … third runner up … second runner up. Then “Miss South Carolina USA!” She was first runner up.

It was an amazing moment for Amanda Pennekamp — now Amanda Pennekamp Bluestein — the result of years of hard work.

More than anyone knew.

She had a big secret that she didn’t tell the millions of viewers watching Miss USA, a secret she is now comfortable sharing with the world: The pageant winner and model was born with a congenital heart defect that threatened to dramatically alter or even end her life. A lifetime of care from the Children’s Hospital of Georgia had helped her to this moment.

Amanda Pennekamp Bluestein and her mother, Wanda Pennekamp.

Amanda Pennekamp Bluestein and her mother, Wanda Pennekamp.

“Proving everybody wrong”

At the age of 18 months, her parents were informed that she had aortic valve disease, in which the valve between the main pumping chamber of her heart and the main artery didn’t work correctly.

“Amanda had been hospitalized for dehydration,” said Bluestein’s mother, Wanda Pennekamp. “The pediatrician noticed that her heartbeat was very loud.”

When the Pennekamps were informed of her condition, they were told that their daughter would probably need open heart surgery sooner rather than later, but there was no way to know exactly when. They were also warned that she should not involve herself in strenuous activity, such as competitive sports, and she would be unable to have children.

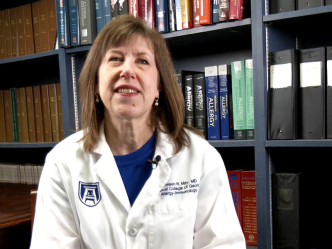

When Bluestein was in preschool, her parents first brought her to what was then the Medical College of Georgia Hospitals and Clinics. The family met with Dr. William Strong, whose view on dealing with young cardiology patients was somewhat out of the mainstream at the time.

“One of the main things that I stressed as far as any child with heart disease is concerned, is I did not want them to restrict their physical activity in any artificial way,” Strong explained, and Bluestein was no exception. “The family and Amanda were aware that at some point in the future, the lesion she had would progress to the time when she would require surgery. I explained to the family exactly what the condition was, how it differed from normal, and encouraged the child to be as active and normal as possible. One reason for that is that no child wants to be different than any other child. With that kind of encouragement, Amanda did everything she wanted to do.”

With Strong’s positive reinforcement, Bluestein lived an active life throughout her childhood and teenage years, taking part in sports and cheerleading.

“Luckily because we got the worst-case scenario to begin with, she kept proving everybody wrong,” said Pennekamp.

Bluestein had such a busy life, she would often forget that she even had a heart condition unless someone reminded her. At the same time, she didn’t want to mention it to others.

“When I was younger, I felt like a science experiment or a freak of nature,” she said. “I felt like the more that I talked about my heart problem, the more I thought that there was something wrong with me.”

The Columbia, South Carolina, resident continued to come to Augusta annually to have her heart checked by Strong (at what’s now known as the Children’s Hospital of Georgia) to see if her condition had worsened to the point that she needed open heart surgery.

“Every year it came time for this to happen, I thought ‘Is this the year? Is this the year?’” she said.

Going for the crown

Strong continued to give her permission to live a normal life as she did not yet need surgery, and she took every opportunity she could, including a big one that came her way at the age of 14.

She danced in a high school talent show and was noticed by Cyrus Frakes, a pageant director and producer, and owner of the company Gowns and Crowns, which prepares young women for pageant competition. He asked Bluestein if she had ever thought of entering pageants. “That’s where the pageant bug started,” she said.

She began to get involved in the pageant world, and by the age of 22, she won Miss South Carolina USA, leading to that surreal moment when she found herself as a finalist for Miss USA.

But that was far from the end of her pageant and modeling career: She went on to win the very first Miss Earth United States pageant allowing her to represent her country in the environmentally-themed Miss Earth pageant in 2006.

Throughout that time, Bluestein and her family didn’t have any concerns that her condition might affect her ability to compete. She started teaching Zumba classes, another thing that her parents had been told early on that she wouldn’t be able to do. It wasn’t until Bluestein’s pregnancy several years later that there were any worries.

“When she got pregnant the first time, I was a basket case,” said Pennekamp. “It was awful. I kept hearing in the back of my head what they told me to begin with. I was over in the corner, feeling nervous.”

Bluestein was a high-risk pregnancy and had more frequent doctor appointments, along with multiple echocardiograms. She successfully delivered a son in 2012 and a daughter in 2015.

Bluestein at the Children’s Hospital of Georgia in February, just after open heart surgery.

Bluestein at the Children’s Hospital of Georgia in February, just after open heart surgery.

A heart that needed mending

By the time her second child, a daughter, was born in 2015, Bluestein had won another title, Mrs. Galaxy, but she started to regret not being more open about her condition in public. (The only procedure she had had done at this point was a heart catheterization in 2013.)

“Looking back, I wish I had made congenital heart defects my platform,” she said.

In the meantime, Bluestein continued to have routine visits with a local cardiologist in Columbia, as Dr. Strong had retired from seeing patients in 2003.

She said that with every visit, “We would wait on pins and needles: ‘Okay, is this the time for the surgery?’”

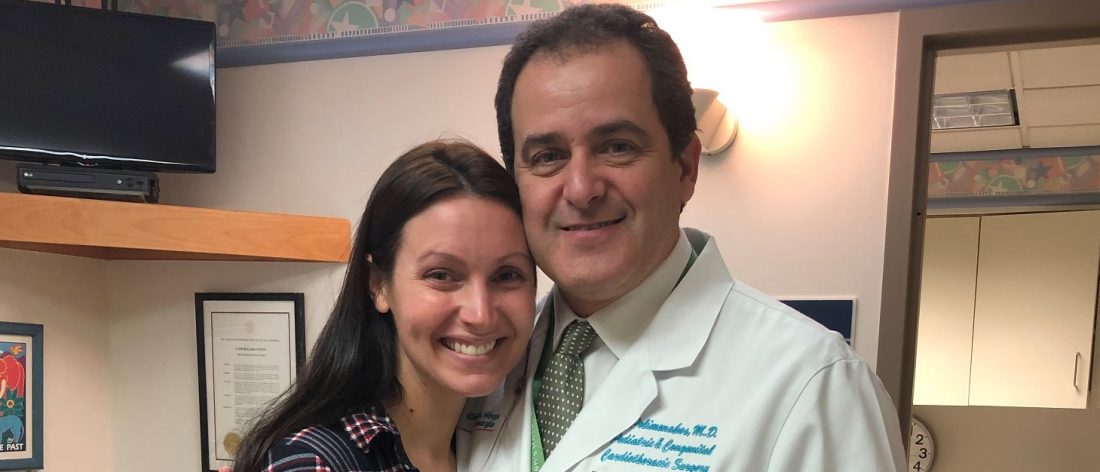

Around this time, Pennekamp started to notice that her daughter seemed extremely tired. At first, Bluestein shrugged it off as due to a busy life and raising two children. But it seemed like this wasn’t normal. It looked like the time had come for surgery, so Bluestein decided to return to the Children’s Hospital of Georgia. She met with Dr. Anastasios Polimenakos and Dr. Kenneth Murdison late last year and in January of this year to see if her aortic valve could be repaired or replaced.

“The valve had begun to leak significantly,” explained Strong, who has remained in touch with Bluestein. “The left side of the heart had to work overtime more than was necessary. The heart was facing strain.”

After looking at her heart with an ultrasound, Polimenakos and Murdison recommended that she have open heart surgery. Polimenakos was to perform the surgery in February.

This was the first time that Bluestein was nervous about anything involving her heart condition. The moment when she was wheeled into the operating room, clutching her teddy bear, Elvis, was very emotional.

“I did have a few tears and I told my husband as he was walking back with me, ‘If something happens, make sure to tell everyone that there’s a note for them on my phone,’” she said.

Despite her nervousness, Bluestein was confident that her surgery would go well.

“I felt in my gut that nothing was going to happen,” she said, starting to tear up. “I get emotional just thinking about it, because I will never ever be able to thank them enough and repay them, because they were so patient and thorough with me and they still are, and they treat me like a human. I knew I would come home to my husband and my babies because I was with them. I asked them to pray with me, and they did. I wish anyone in this world could get that kind of treatment and care.”

The surgery was a success, and Bluestein — who now works at Cyrus Frakes’s at Gowns and Crowns as a professional pageant instructor — wants to let the world know that she has been able to live for 37 years thanks to the great care and the technological advances at the Children’s Hospital of Georgia.

“I would not go anywhere else. Nowhere. Else,” she said. “The care that I have received here has been out of this world. The treatment I’ve been given here is one in a million. I can’t say enough wonderful things about this place, and I wouldn’t have any kind of procedure anywhere else now.”

Augusta University

Augusta University