It’s a chilly Friday afternoon, and in the Natalie and Lansing B. Lee Jr. Auditorium, the mood is decidedly somber.

It’s a chilly Friday afternoon, and in the Natalie and Lansing B. Lee Jr. Auditorium, the mood is decidedly somber.

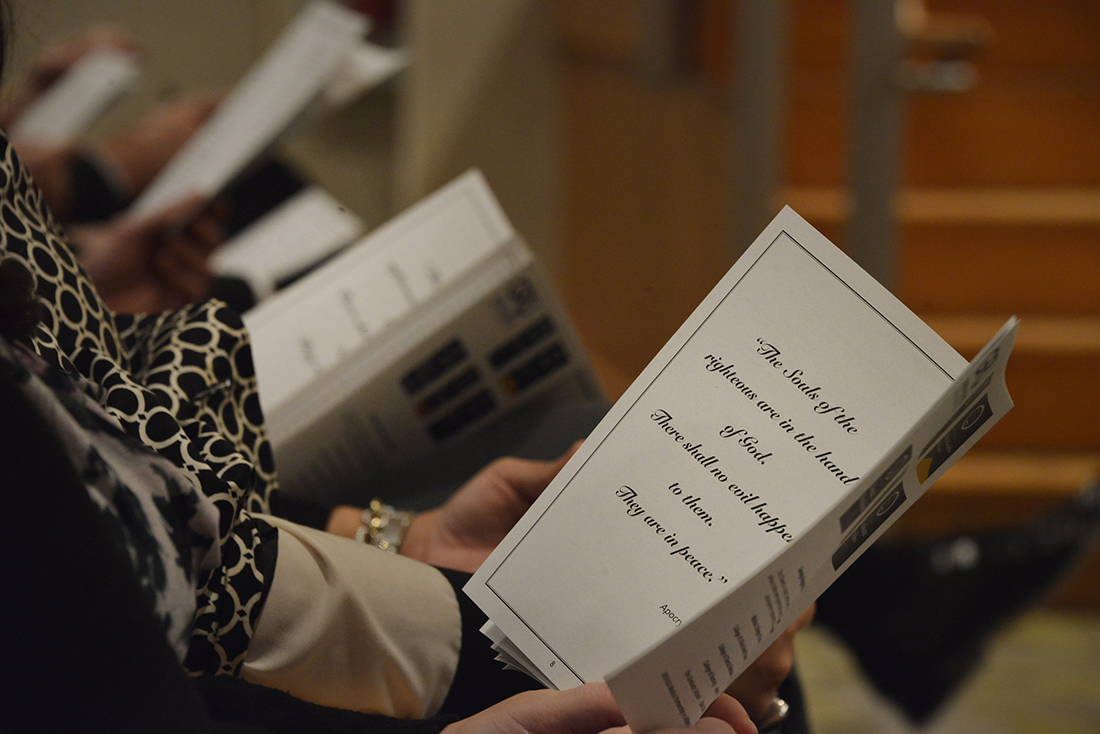

Dressed in their Sunday best, hundreds fill the auditorium’s theater-style seats, murmuring softly to one another about anything and everything. Most seem eager to distract themselves from what is to come.

Three rows from the stage, a young woman cries into her sleeve. In the seat beside her, a small boy mewls loudly to the chagrin of his parents. Despite their tears, however, no voice rises above a whisper to comfort them. Their feeling, their sorrow, is quietly understood.

It is an uncomfortable, but deeply familiar, scene.

They, like everyone else in the room, have lost someone they love.

Though many of the participants have waited a year or more to say goodbye to their loved ones, the memories conjured by the sight of the six flower vases lining the stage revives fragments of their pain. The colored ribbons on each, representing the six student groups who study cadaveric material, are silent reminders of the colorful lives being remembered, of the colorful memories that will live on for years to come.

In that way, the Medical College of Georgia’s Body Donor Memorial carries the same weight and emotion as a more traditional funeral service.

But the true beauty of the MCG memorial lies not in what it shares with other services, but rather, in what is different.

Behind the scenes, the dead are not only fond memories.

They are also valued teachers.

Caretakers, protectors:

It begins the way it ends: With an expression of gratitude.

When potential donors receive their donation information, the first thing they see is a letter addressed from Dr. Sylvia Smith, Regents’ Professor and chair of the Department of Cellular Biology/Anatomy at the Medical College of Georgia.

Smith begins by thanking participants for their interest in the Anatomical Donation Services Program. The gesture seems like a small one, but its impacts is tremendous. After all, the majority of the program’s donations are granted as a thank you – whether to MCG directly or to the doctors, friends and families that made the life lost first worth living.

After thanking potential participants, the letter then goes on to explain how important donations are to the future of anatomical study and the betterment of the health care profession as a whole. It’s a simple message but a clear one.

After thanking potential participants, the letter then goes on to explain how important donations are to the future of anatomical study and the betterment of the health care profession as a whole. It’s a simple message but a clear one.

“We can make this world better,” it says, though the words are left unwritten. “But we need your help to do it.”

According to David Adams, coordinator of MCG’s Anatomical Donation Services Program, there’s a reason the letter reads that way.

“When people make this kind of gift, there’s no telling how much good it might eventually do for mankind,” he said.

With more than 30 years of experience as a licensed embalmer and funeral director in the states of Georgia and South Carolina, Adams knows better than anyone the kind of impact even a single donation can have on the lives of students and educators. He also knows the kind of strain a body donation can place on a donor’s family.

“These folks stay with us for a while,” he said, noting that the shortest amount of time a cadaver will be used is roughly three months.

It’s a tremendous sacrifice for those left grieving.

The key to acknowledging that sacrifice, he said, is showing the fallen the utmost respect.

A warm and amicable group, Adams and his fellow embalmers are solemn in their duty to the dead. They are quick to refer to their wards as cadavers rather than bodies and take the time to ensure their work is performed carefully even under the most stressful conditions. Under their watch, the dead are treated not as a part of the student curriculum, but rather as they should be.

As honored guests.

“I call them visiting professors,” Adams said, smiling. “They’re the students’ first patients, and the students learn more from them than they ever will in a normal classroom. I guarantee you that.”

More often than not, he said, the students consider their cadavers the most important people in the room. There’s a reason for that, too. From arrival to interment, the process Adams’ team has in place has the feel of a distinguished funeral service.

David Johnson, an anatomical embalmer, said a lot of that perception comes from the way he and his team view themselves.

“We are the dead’s caretakers,” he said. “We are their protectors.”

But without a doubt, the rest comes from Adams’ insistence on doing things by the book.

A tradition of honor:

When Adams first came to Georgia Regents University in 2002, the Anatomical Donations Service Program was slightly different from the one that exists today. In fact, the public’s perception of cremation as a whole was on somewhat shakier footing.

In February of that year, the Tri-State Crematory scandal broke, gaining national attention almost overnight.

In total, more than 330 bodies were discovered on the grounds of the family-run crematory in north Georgia. For years, the crematory had neglected to cremate the dead. Instead of their loved ones’ remains, it turned out, the crematory had been sending grieving families packages of concrete dust.

The discovery led to a national investigation and a conversation about the ethics of cremation. That conversation, Adams recalled, began at home.

Having taken on the role of coordinator in April of 2002, Adams said his foremost concern was ensuring the public understood that MCG had absolutely no part in the scandal.

“Thankfully, I was able to say we had never sent bodies to that crematory,” Adams said. “This was happening right as I was starting, and my biggest concern was making sure we were honoring the dead. And we were.”

But things weren’t what they could have been.

When Adams took on the role of coordinator, the memorial service he inherited was efficient and respectful, but it wasn’t nearly as personal as the current MCG Body Donor Memorial.

“They were going to have the combined service for body donors in Decatur Cemetery,” he said. “I went to that for several years. And I don’t mean to be critical of it, but I thought when they handed me a printed sheet of the 23rd Psalm, ‘we could do better than that.’”

But the system in place was an effective one. When Adams challenged the way things were being handled at the combined service, he said the response he received was, “No thank you, we’ve got it the way we want it.”

“So I came back after the one, I think it was in 2003, and my chair asked me the next Monday, ‘How did it go?’” Adams said. “I said I was very disheartened with that. I said we can do better.”

Driven by his years of experience as a certified funeral services practitioner, Adams began thinking of ways to create a memorial that was as unique, respectful and dignified as a traditional funeral service.

The first step, he said, was finding ground worthy of the memorial. Unfortunately, the task proved more difficult than anyone had hoped.

Adams and his team spent a great deal of time looking for a suitable burial plot, both on and off campus, before the way was eventually made clear.

“You know the saying ‘doors get slammed in your face and God opens one?’” Adams said. “Well, we got one opened.”

The way, it turns out, was through an old willow tree that once stood where the cinerarium lies now.

The way, it turns out, was through an old willow tree that once stood where the cinerarium lies now.

“There was a huge willow tree out there – I mean this thing was tremendous,” Adams said, referring to the current cinerarium plot, located just outside the Carl T. Sanders Research and Education Building. “And it was one of these freak storms that came through off the tail end of a hurricane. It took that tree out. I mean it just pulled it up out of the ground, and there it sat one morning.”

Adams said as soon as that happened, a landscaper remarked, “Well, I think that’s your plot of land.”

With that door opened, Adams embarked on creating what is perhaps the most remarkable, if not the most respectful, portion of the current memorial service.

“It dawned on me one day that, as a historical institution, we should have something that feels just as historical to commemorate our dead,” he said.

His answer was the Book of Remembrances.

Hand sewn into a gorgeous, leather-backed binding, the Book of Remembrances is an impressive modern-day artifact. On its cream-colored pages, the names of each of the fallen are painted in a beautiful handwritten script by a talented calligrapher. If any of those names is ever misspelled or if the handwriting doesn’t meet her satisfaction, the artist cuts out the entire page and begins again.

“She doesn’t make too many mistakes,” Adams joked. “Or if she does, she doesn’t tell me about it.”

This year, 162 names joined the ranks of MCG’s honored dead. Immortalized in print alongside hundreds of other donors, the implicit promise is that those held within the book’s bindings will far outlive the young professionals who learned from their sacrifice.

“It’s quite an elegant way to do it, in my opinion,” Adams said.

And it’s a tried strategy. Adams said he experienced something very similar at the Trinity College School of Medicine in Ireland.

“What they do is print their names on a sheet in a similar font to the one we use and place it directly into their book,” he said. “It saves them money, but it’s nowhere near the perfection ours represents.”

However, if the memorial service provided for the families approaches perfection, then the one the students give more than hits the mark.

A life of service:

Seated among the families and the faculty in Lee Auditorium, another group of mourners have gathered.

Some take to the stage, playing instruments, telling stories and leading prayers. Others usher family members to their seats. In many ways, the service belongs as much to these visitors as it does to the fallen, though cynics would call them onlookers. Gawkers. Trespassers.

Most everyone recognizes them for what they are, though.

Friends of the deceased.

Of all the people in the room, these mourners know the dead best.

They knew who they were, how they lived and what ultimately claimed their lives. From the deceased, they have learned more about humanity, more about themselves, than any professor could ever hope to teach.

It’s a lesson they will never forget.

According to Adams, it isn’t uncommon for students to form that kind of emotional bond with the donors they work with. Though there’s no written rule or suggestion to do so, many name their cadavers in the first week of study. Like Adams, they view their donors – their patients – as people.

Given only a job title, an age and a cause of death, they make it their mission to piece together the life story of someone they never had a chance to meet.

In so doing, they, too, share their thanks with the dead, albeit in a rather unconventional way.

“Sometimes, as we’re preparing the cadavers for cremation, we find little notes hidden under the white sheets we use to cover the deceased,” Adams said.

In the 13 years he’s worked at MCG, he swears he’s never read a single one.

“It’s none of my business,” he said. “What’s on those notes is between the students and the dead. It isn’t for me.”

Traditionally, he said, the notes go with the bodies into oblivion.

But on one occasion, they didn’t.

“A while ago, a couple of students were working with a cadaver, a big, gruff-looking guy, looked like he’d probably fought in Vietnam,” Adams said. “They called him The Colonel.”

It was the only thing students knew about their patient, an otherwise nameless cadaver. In life, he’d been a colonel.

That common thread, devoting his life to serving others just as they were sworn to, was enough for the students to form a lasting bond with their cadaver.

That common thread, devoting his life to serving others just as they were sworn to, was enough for the students to form a lasting bond with their cadaver.

“They just loved this guy,” Adams said, chuckling. “I mean, they had so many stories about him.”

When the time came to send The Colonel on his way, the students did what most do. They said their goodbyes and their “thank-you’s,” and they wished his spirit well. But rather than consigning their notes to the fire, as so many others do, these students did something extraordinary.

“I remember the man’s son came to the service that year,” Adams said. “The students found him, found his name, and they gave him their notes.”

The son’s response, Adams said, was indescribable.

“He was just so touched that these students who had never even met his father loved him so much,” he said. “He was proud that, even in death, his father had still served.”

But the students who work with cadavers don’t just make their own stories. Sometimes, they tie the experience to the stories they have already lived.

Such was the case for Faysal Akbik (MCG Class of 2019).

“I found myself working with a school superintendent who lived for 91 years before passing of congestive heart failure,” he said. “For me, he reminded me of my grandfather, who passed nearly a decade ago.”

Akbik said his grandfather, a refugee from Syria, worked for UNESCO as a literacy program coordinator, building customized programs for illiterate populations in Africa. His wife traveled with him, serving as a school principal.

“I shared this story because when everything was taken away from my grandfather, he gave back through service,” Akbik said. “Everyone that we are gathered here to honor today also made the decision to give back.”

The fondest farewells:

As the memorial comes to a close, the families and friends of the deceased gather in the auditorium’s main lobby.

The next step is interment, which, for many donors, is the end of a journey longer than life.

Few would argue that the cinerarium is a truly beautiful plot of land. That a gorgeous tree died to produce it is fitting for the memorial’s theme of making the ultimate sacrifice. That sacrifice, like so many before it, is also greatly appreciated.

For there, consecrated, the donors’ remains enter the waiting earth where they will rest eternally.

But they will never really be gone.

In the minds and hearts of their families, their friends, they will live on forever.

And they will live on forever in the hearts and minds of those they taught after death.

For these fallen, then, the fondest farewells aren’t the final goodbyes they receive on a chilly Friday in November.

No, for these fallen, the fondest farewells are the lifetime of “thank-you’s” they’ll receive for their last and greatest gift.

Augusta University

Augusta University