By Nick Garrett

During the 2008 election cycle, few figures were more polarizing – or more talked about – than Professor William “Bill” Ayers.

At the time, his alleged connections to then-Senator Obama touched off a media firestorm that led to a plethora of questions from both sides of the aisle. The issue for most wasn’t Ayers’ political leaning or his stance on education reform, both radical in their own right. It wasn’t his money or even his connection to prominent political figures.

For most, the concern was Ayers’ past.

Now a retired professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, Ayers is perhaps best recognized for his role in co-founding the “Weather Underground,” a radical left-wing organization responsible for a string of bombings in the early-to-mid ‘70s.

Born out of the countercultural movement, the Weather Underground’s mission was simple. Its leaders, including Ayers, lived and worked as educators and radicals, students and bomb-makers – each, in his or her own mind, determined to make the world a fairer, freer place. Their goal? The complete overthrow of the United States government.

Though their attacks accomplished relatively little, some hailed the Weather Underground as heroes of the countercultural movement. Others called the organization’s members terrorists, communists and traitors.

Time has not changed most peoples’ perception of the Weather Underground. In some ways, though, time has changed Bill Ayers.

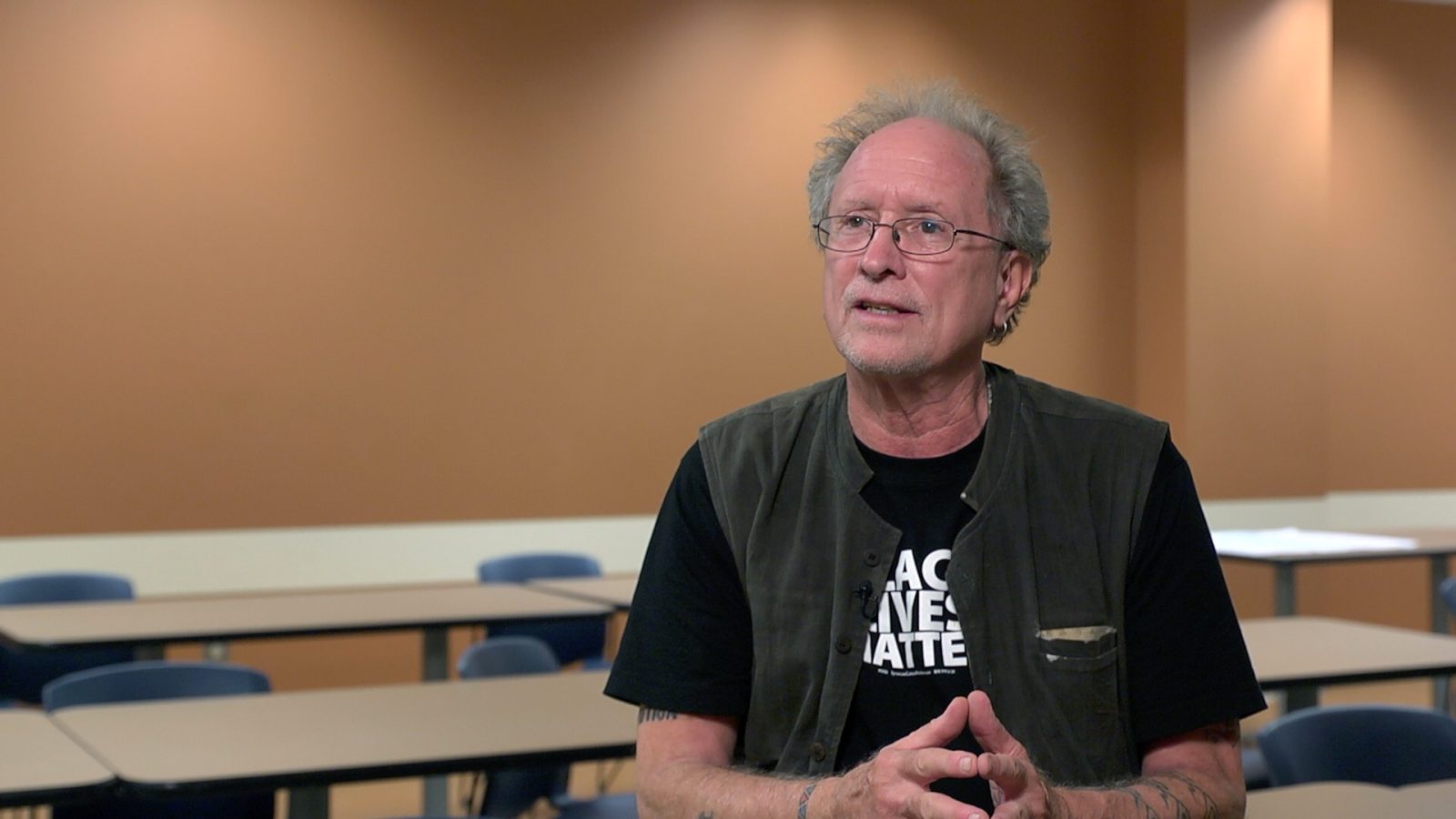

His hair, once defiantly long, is now tightly cropped and verging on silver. His Weathermen tattoos, once vibrant symbols of the movement he co-founded, are now dull and faded with age. And while he still champions the voices of the oppressed, he seems content to do so now from the comfort of a podium rather than the squalor of a jail cell.

But during a recent visit to Georgia Regents University, Ayers talked about the one thing that time hasn’t changed – his fight for social justice.

“I think of [social justice] as different groups of people in dramatically different contexts and different historical moments coming together to fight for more equity … more recognition,” Ayers said.

Wearing a Black Lives Matter T-shirt, Ayers said recognition was the most important part of any social justice movement. Many would agree with him. This week alone, the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter has reached an estimated 4 million Twitter users. Another popular social justice hashtag, #TransLivesMatter, isn’t far behind at 1.5 million.

But recognition is about more than just being noticed, Ayers said. It’s about understanding – and overcoming – privilege.[mks_pullquote align=”right” width=”300″ size=”24″ bg_color=”#ffffff” txt_color=”#0e314b”]”Privilege means having the opportunity to be able to choose, the opportunity to be able to move, to have some mobility. Frankly, everyone you know and everyone I know have privilege.”[/mks_pullquote]

“Privilege means having the opportunity to be able to choose, the opportunity to be able to move, to have some mobility,” Ayers said. “Frankly, everyone you know and everyone I know have privilege.”

It’s a sobering concept, if a difficult one to explain. Ayers said he witnessed one of the most poignant examples of privilege while teaching in Chicago.

“When I was first teaching at this urban university in Chicago … my classes went from five to nine at night and were on the west side of Chicago in a pretty sketchy area,” Ayers said. “It took me about two months to notice that the women, when class ended, all gathered at the corner of the room while the men all went to their cars in the parking lot.”

After two months of teaching, Ayers finally reached out to the young women to ask why they were staying after his classes.

“Well, because it’s not safe to go out alone,” they told him.

None of the men in Ayers’ class exhibited the same kind of behavior. Not one of them felt the need to walk in a group to their cars or to travel in pairs to the train station. Because of that, Ayers said his privilege as a man had anesthetized him to the realities faced by another group – in this case, the young women in his class who were afraid of being attacked on their way home from school.

“I didn’t notice, not because I’m a bad person, not because I’m willfully ignorant, but because my privilege allowed me not to notice,” Ayers said. “That’s all I mean by privilege.”

It’s not an accusation, nor is it a condemnation, Ayers stressed. In his eyes, acknowledging privilege is simply a fact of life, a part of growing both intellectually and empathetically.

“And the beautiful thing about privilege,” Ayers said, “is that when you see it and recognize it, there’s a place for you, no matter who you are, in overcoming it.”

The most recent and groundbreaking instance of overcoming privilege in America, Ayers said, was the recent Supreme Court decision to legalize gay marriage. But even in the wake of that momentous decision, he said, “straight privilege” still exists.[mks_pullquote align=”left” width=”300″ size=”24″ bg_color=”#ffffff” txt_color=”#0e314b”]”It’s very hard for straight people to see the ways in which gay people are discriminated against. Why is it hard for them to see it? Because they don’t feel it, because it doesn’t happen to them.”[/mks_pullquote]

“It’s very hard for straight people to see the ways in which gay people are discriminated against,” Ayers said. “Why is it hard for them to see it? Because they don’t feel it, because it doesn’t happen to them.”

To overcome privilege, one must first recognize its existence. To have any lasting effect, the decision to recognize privilege must also be a conscious one. It seems simple enough, but getting people to that point is another challenge entirely.

And according to Ayers, it’s one educators can help their students – and the public – to understand.

“One of my definitions of a bigot is someone whose imagination is damaged,” he said. “The great thing about education is that it can feed and nourish your imagination and challenge it.”

Unfortunately, the one common threat faced by educators and students alike, he claimed, was that not all have a choice about the quality of the education they receive. Not everyone has that privilege.

“I think there’s a national consensus that urban schools for the children of the poor and the children of formerly enslaved peoples and the children of recent immigrants of poor countries are failing those children,” Ayers said. “There’s no consensus about how to fix it or whether we even should fix it.”

For much of the last 40 years, Ayers said he’s been actively engaged in trying to address that problem. And on the surface, it seems like the sort of issue that would be easy to fix.

“Education is a human right,” he said. “It’s encoded into Article 26 of the Declaration of Human Rights from 1948, but it’s also the one thing that’s in every state constitution – the idea that children who are born in this state have the right to education.”

The trouble is, not every state lives up to that promise. The issue, Ayers claims, lies with education reform. More specifically, the issue lies with the notion of corporate education reform.

“I think the people who are taking us in the direction of privatization of the public space, who are taking us in the direction of doing away with the teacher’s unions, who are taking us in the direction of reducing education to a simple, single metric … are going in the wrong direction,” Ayers said.

The solutions that we seek, he said, have to be public solutions. He likened corporate education reform to viewing education as a product, such as a laptop or a printer, and claimed that while the metaphor was convincing to some, it was a bad metaphor at its core.

His reasoning?

The “choice” education reformers are proposing for underprivileged families isn’t really a choice at all, he said.

“What do you get at the Lab School?” Ayers asked, referring to the University of Chicago Laboratory School, a private, co-educational day school in Chicago. “A cap on the class size at 18, a curriculum based in part on pursing your own questions and interests, five libraries, a full arts program ….”

Right down the block, Ayers said, the city and state advocate for schools that cap their class sizes at 40. These schools have no arts programs, no athletics programs and no self-driven curriculum. In fact, in 2010, an estimated 160 schools in Chicago were missing a library. Since then, that number has only grown.

“The mayor would never send his kid to that school,” he said. “So how can he, in good conscience, advocate for these kinds of charter schools which really just replicate the worst of what’s already there and already failing these kids?”

Ayers admits privilege has a great deal to do with the decision to advocate for these types of schools. That said, he was also quick to admit his own. His own children graduated from the Lab School, and so, he hopes, will his grandchildren.

The solution, he said, lies not with taking privilege away from those who have it, but bestowing equal privilege to those without it. The power to do, he said, lies in the hands of educators.

Step one is figuring out how to support them.[mks_pullquote align=”right” width=”300″ size=”24″ bg_color=”#ffffff” txt_color=”#0e314b”]“If I get to the microphone first, I say every kid in a public school deserves an intellectually grounded, morally committed, caring and compassionate, well-rested and well-paid teacher in the classroom. And I would invest my energy in holding up teachers.”[/mks_pullquote]

“If I get to the microphone first, I say every kid in a public school deserves an intellectually grounded, morally committed, caring and compassionate, well-rested and well-paid teacher in the classroom,” he said. “And I would invest my energy in holding up teachers.”

Overwhelmingly, Ayers said teachers come because they have something to share. It’s a beautiful thing. And it’s something he believes should be protected by preserving the collective voices of teachers’ unions.

But step two is even more pressing: funding schools fairly.

“That means that we don’t fund schools on the North Shore of Chicago at $80,000 per kid per year and we give funds in the city to half, or a third, of that,” Ayers said. “It’s not reasonable, and it’s not fair.”

When it comes to children, he added, U.S. policy is “choose the right parents.”

“If you choose the right parents, you get to go to a good school, you get to live in a neighborhood with clean air, you get to have a park, you get to have a police force that doesn’t feel like an occupying force,” Ayers said. “That’s absurd in a democracy.”

What the wisest, most privileged parents choose for their kids, he said, should be the choice of their community as well.

“Anything less destroys democracy,” he said.

Ayers maintained that moving toward a system where that kind of choice is possible is one of the greatest steps society could take toward lessening the privilege gap that currently exists between American children. Whether or not the U.S. chooses to move in that direction, he made it clear that he believes education must be reformed in order to keep privilege from deciding the course of future lives.

It’s a matter of dignity, he said. A matter of intellectual growth.

In short, a matter of democracy.

If there’s a single most important point to take away from Ayers’ message, then, it is this: How dire must the situation of modern education be when one of the loudest voices in defense of democracy is a man who once fought so diligently to see it ended?

Only time will tell.

Augusta University

Augusta University