Concerns about the safety of the LGBTQ community, financial health and intimate partner violence can have an effect on physical health among sexual minorities, according to researchers at the Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University. Those worries seem have more influence than experiences with discrimination.

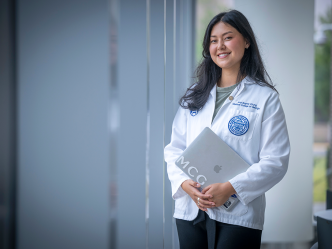

It’s been well researched and widely accepted that sexual minorities experience stressors, like discrimination and safety concerns, which have been linked to many physical and mental health conditions, says James Griffin, an MCG psychology intern studying with Dr. Lara Stepleman, director of HIV and Multiple Sclerosis Psychological Services for the medical school.

“The effects of minority stress on things like mental health have been widely reported, but recently researchers have begun looking at how it’s related to other health outcomes,” Griffin says.

“We wanted to look at lifetime experiences of stigma or discrimination and how that might influence physical health, but we also wanted to look at a number of other variables that are very much related,” he says of the MCG study, which is being presented by Stepleman at the Annual Meeting of the American Psychosomatic Society this week in Sevilla, Spain.

Recent studies by the Williams Institute, a legal research group out of the University of California, Los Angeles School of Law that advocates for sexual minorities, have shown that the southern region, as a whole, is a poor social climate that is not perceived as a safe place for the LGBTQ community. Those perceptions are based on prevailing attitudes toward same-sex rights, legal protections, even general attitudes. Their studies also showed that sexual minorities in the south have the lowest rates of health insurance and that same-sex households have significantly lower incomes, which could be due to things like discrimination in of hiring. Nationally, sexual minority men also experience elevated rates of intimate partner violence.

To find out how those variables relate to physical health, researchers asked 241 lesbian, gay and bisexual adults in and around Augusta, who had participated in a larger community health needs assessment run by Stepleman, about their experiences with discrimination, intimate partner violence, perceptions about safety in the community and their current financial concerns. They also asked participants about the number of days they’d felt poorly in the past month.

Griffin and his colleagues found that people reported a greater number of days that they didn’t feel well when they had experienced concerns about finances and safety of LGBTQ individuals in the community. These concerns outweighed effects of lifetime experiences with discrimination. In fact, most respondents – 65 percent – said they had not experienced a major form of discrimination based on their sexual orientation.

“These findings suggest that lifetime experiences of discrimination are not as directly influential on recent physical health,” he says. “Experiences with partner violence, poor financial situations and the perception that the area is unsafe actually have more influence on perceived physical health. We know from research that self-perception of health is actually linked to biomarkers of poor health.”

There’s a dearth of research in this area, so follow-up studies could look at how each variable specifically influences behaviors related to health outcomes, like seeking support, Griffin explained.

“But a big part of it is advocacy,” he says. “There’s a need for better health care resources for sexual minorities and a greater network of support that includes a visible community where there are places to go, people to talk to, for someone who has been victimized for instance, and resources for people who are struggling financially.”

Augusta University

Augusta University