Augusta University researchers are investigating a protein found in the tears of preterm babies in the hopes of developing a better treatment for retinopathy of prematurity, a condition leading to blindness in about 500 infants each year.

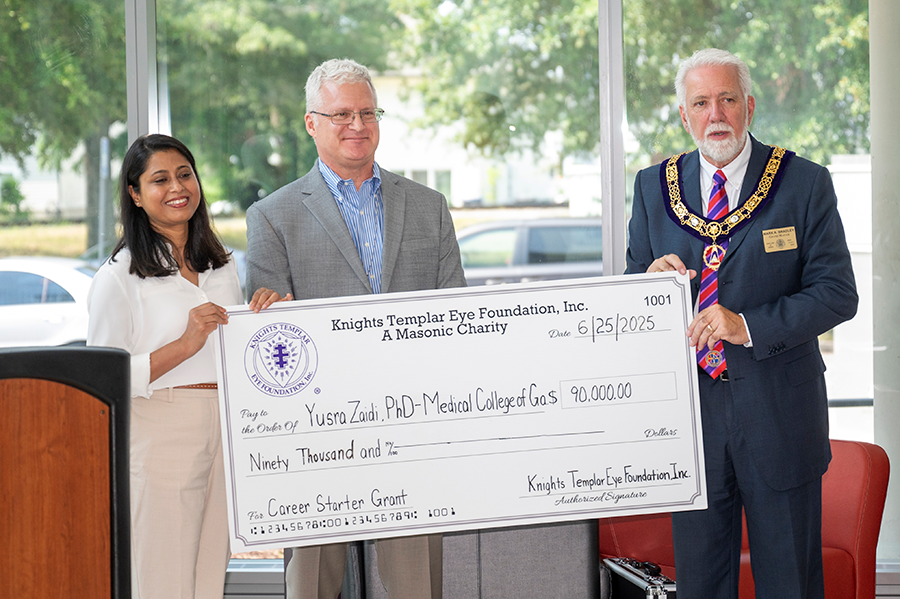

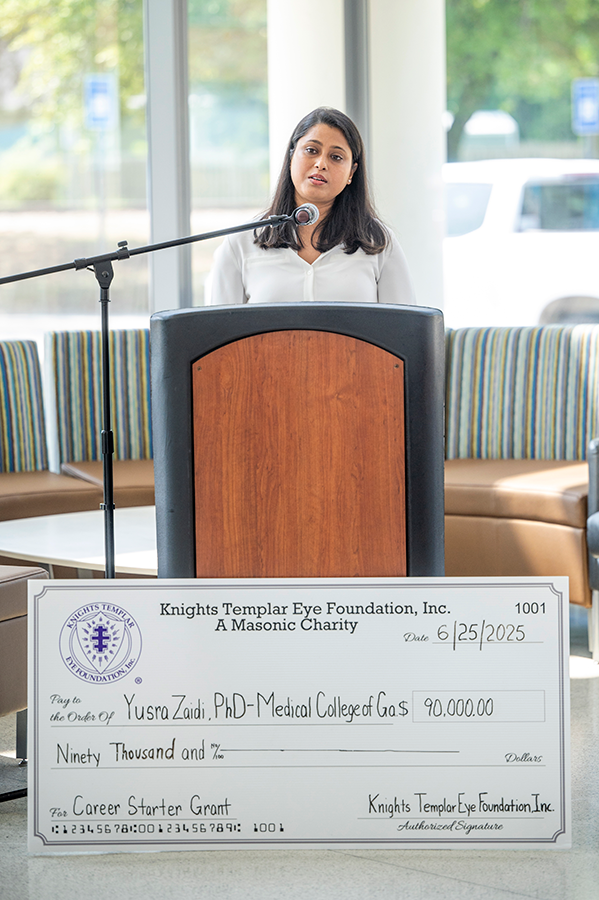

The Knights Templar Eye Foundation Inc. recently awarded a $90,000 grant to Yusra Zaidi, PhD, a postdoctoral research fellow in the Vascular Biology Center of the Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University, to explore how the naturally occurring protein Apolipoprotein A1, also known as ApoA1, could potentially prevent retinopathy of prematurity in this young and vulnerable patient population.

“When an infant is born too soon, especially before 28 weeks of gestation, the retina hasn’t finished developing. That incomplete development can result in permanent vision loss in some premature infants,” Zaidi said. “As a mother, I often think of these babies who have never even had the chance to see their parents’ faces or the colors of the world. These little ones cannot speak of their pain or what they are going through.”

Ironically, the baby’s tears may hold treatment clues. Zaidi and her team discovered that ApoA1, a protein known for its protective effects in the cardiovascular system, is elevated in the tears of preterm infants.

“We believe it’s trying to protect the retina,” she explained. “It’s already part of the body’s defense system; it is a carrier protein of good cholesterol. We just need to understand how to harness it.”

The retina is the tissue at the back of the eye that senses light and sends signals to the brain for sight. With retinopathy of prematurity, unwanted blood vessels grow on the baby’s retina that can cause serious eye and vision problems.

“If retinopathy of prematurity is treated early, vision can be improved or saved, and we can protect the future of these infants,” Zaidi said.

Based on preliminary data, Zaidi hypothesizes that Apolipoprotein A1 has the potential to prevent the formation of abnormal blood vessels on the retina and to protect the eyes from inflammation. Retinopathy of prematurity occurs in about 14,000 preterm babies every year, according to the National Institutes of Health. The tiny blood vessels of the retina begin to develop in the fourth month of pregnancy and finish around the ninth month, or 40 weeks. But babies born under 30 weeks or weighing less than 3 pounds are at elevated risk.

Most preemies with retinopathy of prematurity have mild cases that improve without treatment, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But some babies need treatment to prevent vision loss or other eye problems. Babies with advanced retinopathy of prematurity may need laser treatment to remove abnormal vessels on the retina and, in other cases, anti-VEGF therapy, where medication that is injected into the eye is given to stop the abnormal vessel growth, which can pull the retina up off the back of the eye, resulting in a type of retinal detachment that causes irreversible blindness in up to 600 babies each year.

“Despite the promising outcomes of anti-VEGF treatment in retinopathy of prematurity, there are concerns that the effect may be transient with later retinopathy of prematurity recurrence, or it might have potential adverse effects on normal angiogenesis vessel growth in the neural retina of preterm infants,” Zaidi said, adding that “current treatments are limited and stressful for already-fragile infants.”

She has great expectations for this research.

“I am very hopeful about this protein. This is something already inside the body, synthesized in the liver,” she said. “If we can prove that ApoA1 prevents abnormal blood vessel growth and inflammation in the retina, we might be able to stop this disease before it ever causes damage,” she said.

Epidemiological and functional studies underline a prognostic value of ApoA1 self-antibodies for several cardiovascular diseases. Zaidi affirmed that researchers are seeing positive results with ApoA1 in diseases like atherosclerosis, which is the hardening of the arteries in heart disease.

Zaidi studies retinopathy of prematurity in the Brian Stansfield Lab in the VBC under the leadership of Brian Stansfield, MD, professor and vice chair of research in the Department of Pediatrics. A physician scientist, Stansfield is also a neonatologist and perinatal medicine specialist at the Wellstar Children’s Hospital of Georgia. Babies in the neonatal intensive care unit at Children’s who are thought to be at high risk of retinopathy of prematurity are screened with eye exams.

“Dr. Stansfield is an incredible mentor and physician,” Zaidi said. “He is inspiring and helps me see the clinical impact of our work, how our discoveries might one day help the babies he’s caring for today.”

As she explains it, this is how basic and clinical scientists collaborate to bring translational research forward – from bench to bedside – to improve treatments, patient care and outcomes.

“His dual role — treating infants in the NICU while guiding research in the lab — is a perfect example of translational medicine, where science meets real-world care,” said Zaidi.

Representatives of the Knights Templar Eye Foundation, based in Flower Mound, Texas, visited Augusta University on June 25, to present Zaidi with a check and to tour the research laboratory. The Knights Templar Eye Foundation supports research that can help launch the careers of clinical and basic researchers who are focused on the prevention and cure of potentially blinding diseases in infants and children.

“When I received the grant notification, it was an amazing experience,” Zaidi said. “To have our work recognized among such an elite group of scientists at this level is incredibly humbling and motivating. It gave me renewed strength and belief that we’re on the right path.”

In 2023, the Knights Templar Eye Foundation awarded a similar research grant to Zaidi’s husband, Syed Adeel H. Zaidi, PhD, a retina neuroscientist in the Vascular Biology Center who also studies retinopathy of prematurity.

Yusra Zaidi said the translational research at Augusta University is being noticed, and it is making an impact globally. For example, after reading about his work with retinopathy of prematurity, a “worried father” in Pakistan contacted her husband “seeking hope” for his child with stage 3 retinopathy of prematurity, she said.

“That message reminded me why we do this,” she said. “Our research is no longer just in the lab — it’s touching lives around the world. This protein may one day lead to a future where no child has to face blindness simply for being born too soon.”

The mission of the Knights Templar Eye Foundation Inc., sponsored by the Grand Encampment of Knights Templar, USA, is to improve vision through research, education and supporting access to care. Since 1956, the foundation has disbursed more than $178 million on research, patient care and education. More than $39 million has been awarded to researchers working in the fields of pediatric ophthalmology and ophthalmic genetics. According to the foundation, somewhere in the world, a person goes blind every five seconds, with over 7 million people going blind every year.

Discoveries at Augusta University are changing and improving the lives of people in Georgia and beyond. Your partnership and support are invaluable as we work to expand our impact.

Augusta University

Augusta University