Nearly one year after COVID-19 began to spread across the United States, the virus continues to strike communities of color with vengeance.

Black, Latinx, Pacific Islanders and Indigenous Americans all have a COVID-19 death rate of at least double that of white Americans.

According to data collected by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, over the past year, Black Americans were 37% more likely to die from COVID-19 than whites; Native Americans and Alaskan Natives were 26% more likely to die from the virus than whites; and Latinx people were 16% more likely to die from COVID-19 than white Americans.

Even as COVID vaccine distribution ramps up across the country, more than 3,000 Americans have died per day on average since the beginning of 2021. Just this week, the United States reached a grim milestone by surpassing 500,000 known coronavirus-related deaths during this pandemic.

While the number of new COVID-19 infections has been slowly declining over the past few weeks — with the United States reporting more than 53,800 new COVID infections this past week compared to almost 200,000 new infections a day last month — Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, estimates COVID vaccines won’t likely be available to the “general public” before late May or early June.

President Joe Biden announced at a recent presidential town hall in Milwaukee this month that the country could get back to normal by “next Christmas.” That’s likely a scary timeline for communities of color across this country that have been devastated by COVID-19.

It could be particularly dangerous for Black Americans, who have been contracting and dying from the coronavirus at rates higher than any other racial or ethnic group in the country, according to the CDC.

Despite these alarming statistics, a new report from the Kaiser Family Foundation found that nearly 35% of Black adults are not planning to get the COVID-19 vaccine.

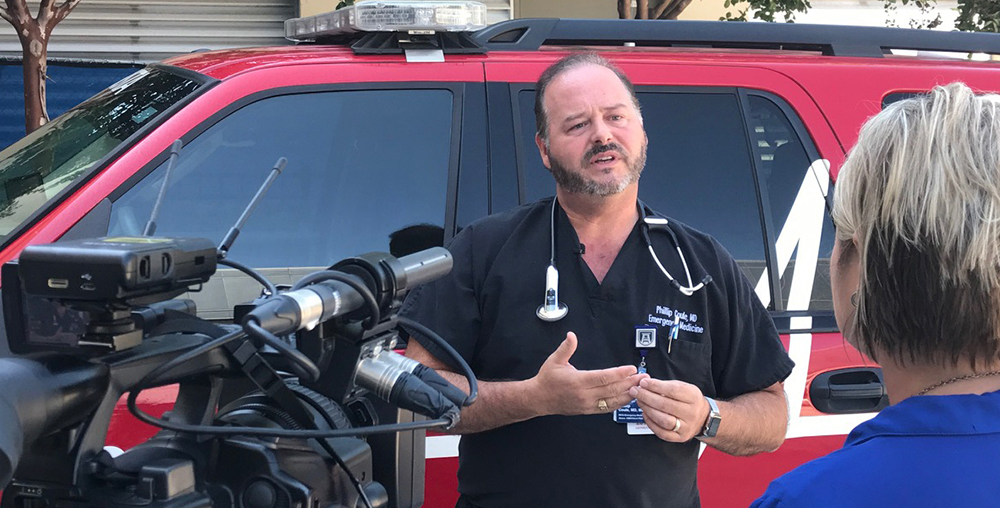

Dr. Phillip Coule, vice president and chief medical officer for Augusta University Health, stressed the importance of encouraging Black Americans to get vaccinated because the risk of COVID-19 is so high.

“We know that the Black and African American communities have been disproportionately affected by COVID-19. In fact, all communities of color have been disproportionately affected by COVID-19,” Coule said. “We’ve actually seen a significant decrease in life expectancy for different groups based on the fact that COVID-19 has devastated certain communities as much as it has.”

Longstanding systemic health and social inequities have put many people from racial and ethnic minority groups at an increased risk of getting sick and dying from COVID-19, Coule said.

The many inequities in social determinants of health, such as access to health care and health insurance, can influence a wide range of health outcomes, he said.

People of color also face greater exposure to the virus, in part because many work in front line and essential jobs, and have high rates of diabetes, obesity and hypertension, all of which are risk factors for severe COVID-19, Coule said.

“We have underlying health care disparities in Black and African American communities and, unfortunately, the more serious health conditions that someone has, the higher the risk someone has of getting sick or dying from COVID,” Coule said. “For example, hypertension over the age of 55 and obesity are actually predictors for poor outcomes from COVID-19. The more those conditions are prevalent in a community, the more at risk that community is.

“Because of that fact, it’s even more important for communities of color to get vaccinated because the risk of COVID-19 is so high.”

There are two COVID-19 vaccines currently being distributed to health care workers, first responders, residents and staff of long-term care facilities and adults age 65 and older in Georgia and South Carolina.

Both vaccines — one from Pfizer and one from Moderna — have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration and are highly effective in protecting people from COVID-19 and preventing severe illness as a result of the virus, Coule said.

Pfizer found its vaccine was 95% effective in preventing the disease among trial volunteers who had no evidence of prior coronavirus infection and in whom no serious safety concerns were observed. Moderna’s vaccine is reported to be 94% effective in preventing COVID-19 and 100% effective in preventing severe illness, Coule said.

“When we compare the COVID vaccine to the flu vaccine, for example, the flu vaccine is approximately 50% to 70% effective because it varies from year to year,” Coule said. “But the COVID vaccines that have been approved and that are available as of today, which includes the Moderna and the Pfizer vaccines, both of them were 94% to 95% effective. That is highly effective for a vaccine. And the two-dose protection really ensures what is probably going to be long-lasting protection.”

The vaccines are not only highly effective, but they also have mild side effects, including reports of slight fatigue, fever, chills and pain at the injection site.

“People need to think about those side effects as a good sign, because that’s your body’s immune system training and revving up to fight this virus, so that if your body sees it again, it can take care of it,” Coule said. “It’s a highly effective, very safe vaccine. I would strongly encourage everyone to take the vaccine when it’s offered to you.”

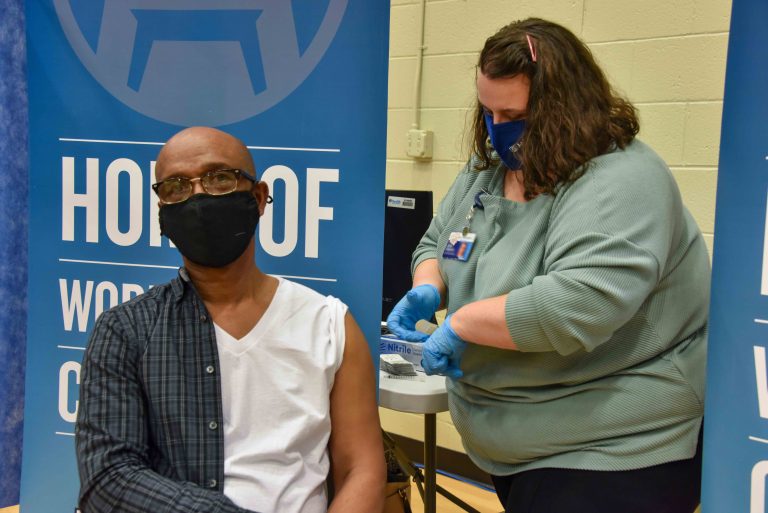

Over the past several weeks, Augusta University Health has partnered with local churches and the Georgia Department of Public Health to provide greater access to COVID-19 vaccines and education through clinics at local places of worship.

Just last month, local church leaders gathered at Good Shepherd Baptist Church to publicly receive their COVID-19 vaccine and encourage more citizens throughout the community to get their shots, too.

“We know that this pandemic has taken a disproportionate toll on underserved communities, including many of those surrounding Augusta University’s campuses,” said Augusta University President Brooks A. Keel, PhD. “As the state’s academic medical center, it is our responsibility to make sure no community is left behind, and that commitment is rooted right here in our home city of Augusta.”

Dr. Justin Xavier Moore, an epidemiologist and assistant professor at the Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University, volunteers with 100 Black Men of Augusta and is working to develop relationships within underserved and minority communities throughout the area. He recently participated in a virtual town hall on Feb. 12 hosted by Augusta University and 100 Black Men of Augusta to discuss the myths and facts surrounding the COVID-19 vaccine.

“Right now, we’re at a very important time,” Moore said. “We, as health care professionals and experts on COVID-19 and the vaccine, need to do a lot of work to address people’s concerns and any of the apprehensions that they might have about the vaccine or anything that they’re hesitant about. We need to try to address it as best as we can, with facts.”

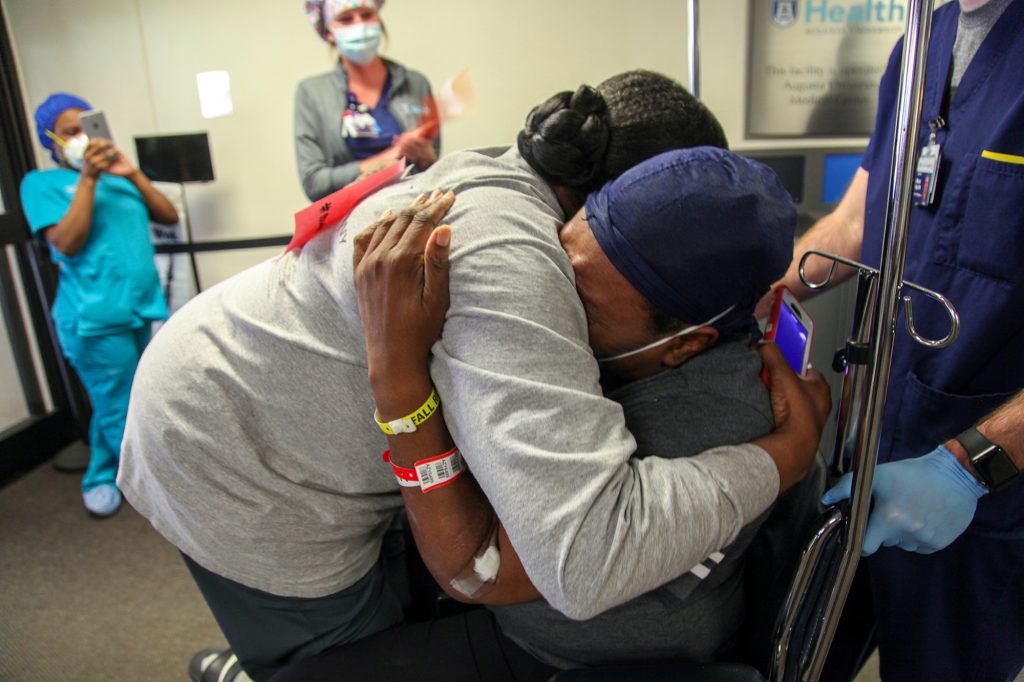

Augusta University Health staff celebrated as patient Caroline Maddox, who had been on a ventilator for eight days battling COVID-19, was released from the hospital in April. Read more about Caroline’s story.

Health care professionals must be honest with the public, especially those living in underserved and minority communities who might distrust the medical community, he said.

“If there’s something we don’t know, then you have to be truthful about that and just let people know that we’re being candid and open. I think that’s the first step,” Moore said. “Because we can’t force anything on anyone. Of course, there’s an urgency here (with COVID-19) because about 3,000 people are dying per day.”

Despite the fact that Black and Latinx Americans have been dying from COVID-19 at more than 2.5 times the rate of white people in this country, some minorities may still have a “low self-perceived risk” of getting severely ill or dying from COVID-19, Moore said.

“There’s a lot of buy-in that you have to do on the public health side to explain why it’s good that you get this vaccine for your common neighbor,” Moore said. “It’s especially tough when one of the main concerns that you hear is, ‘Hey, it was developed too fast,’ or ‘I don’t know what’s going to happen five years down the road.’”

Health care professionals must present the public with solid facts and let people make a decision based on those facts, Moore said.

“So, when you’re talking about African American immunity to COVID with the Pfizer vaccine, the study reported 100% efficacy,” Moore said. “So, of the African Americans included in the study who received the vaccine, none of them developed COVID-19. Zero.

“Now, there were minor side effects such as fatigue, some nausea, site injection pain and fever. But, of course, nothing as severe as dying from COVID. So, the vaccine, in terms of early studies, suggests it is very promising.”

Most health care experts estimate that at least 70% of the population will need to be immune from the coronavirus before COVID-19 can recede through a process known as herd immunity.

Herd immunity means that enough people in a community are protected from getting a disease because they’ve already had the disease or they’ve been vaccinated. Herd immunity makes it hard for the disease to spread from person to person, and it even protects those who cannot be vaccinated, such as pregnant women and newborns.

In the 26 states reporting data on COVID-19 vaccinations, the Kaiser Family Foundation recently found that the vaccination rate among white people was more than three times higher than the rate of Latinx people. In addition, the COVID vaccination rate was twice as high for whites compared to Black Americans.

“The problem is, if we don’t get enough people to buy in, then there’s not going to be any type of benefit. It’s got to be a group effort,” Moore said. “We can’t have 20% of the population do 80% of the work. It can’t be that way. It has to be the 80% of the population does 80% of the work. Otherwise, it’s a lost cause.”

According to the CDC, people of color are more likely to die of COVID-19 by these percentages:

Just last year, Moore, along with his colleagues, Drs. Steven Coughlin, Varghese George and Marvin Langston from the Medical College of Georgia, published a report in the Journal of the American College of Emergency Physicians called “Epidemiology of the 2020 pandemic of COVID-19 in the state of Georgia: Inadequate critical care resources and impact after 7 weeks of community spread.”

Their research reported that during the early months of the coronavirus pandemic, rural southwest Georgia counties with a higher number of Black residents and lower number of ICU beds were experiencing the highest rates of infection and death per capita of COVID-19 throughout the state.

Terrell and Dougherty counties, both included in the Albany, Georgia Metropolitan Statistical Area, along with the southwest Georgia counties of Randolph and Early, had the highest mortality rates in the state during the first seven weeks of the coronavirus pandemic.

Georgia counties with Black populations greater than 50% had a 79% higher incidence rate than those with less than a 50% Black population, and twice the mortality rate. In addition, these more rural Georgia counties also had a lower number of intensive care beds and primary care physicians per 100,000 population, Moore said.

“When the pandemic first hit, it started off in Atlanta, but then literally within that second or third week, it had spread dramatically to the southwest Georgia area around Albany,” Moore said. “The COVID cases stayed high for about two months, with a disproportionate amount of people dying. We observed that those counties were predominantly Black.”

Moore and his colleagues partnered with the Phoebe Putney Health System to study the data of people who were either hospitalized or discharged from the main hospital.

“Basically, some of the main things that we were seeing was that about 90% of all of those who were admitted were African American,” Moore said, adding the hospital quickly reached capacity. “They were just overwhelmed. We, along with the 100 Black Men, were sending PPE to help. You had nurses coming out of retirement to help and we saw that the capacity of the ICU beds, in terms of a pandemic, was very limited.”

As Moore continued to review the data from southwest Georgia, he found these same counties that were identified as hotspots for COVID-19 were also known for higher death rates from diseases like stroke and sepsis.

“There was a cluster of counties right outside of Dougherty County that had a disproportionate amount of people die from sepsis. And we saw the same counties pop up for COVID-19 deaths,” Moore said. “So, what did that tell us? It speaks to a larger issue that the pandemic highlighted or revealed about what we’ve already been seeing with our health care systems in the United States.

“We have a problem and we need to really start rethinking how we care for our people and how we have resources that are available for people. All people.”

Mistrust of vaccines runs deep in African American communities and, in many cases, for good reason, said Dr. David Hess, dean of the Medical College of Georgia.

One of the most egregious examples of medical abuse and neglect of Black Americans was the 40-year-long Tuskegee Syphilis Study, Hess said. In this “study,” more than 400 Black men in Alabama suffered with syphilis and doctors deliberately allowed the sexual transmitted disease to progress without treatment.

As a result of such terrible treatment over the years, medical communities around the country must provide better education about COVID vaccines to Black Americans in an accessible and equitable way. In fact, a recent report by the NAACP and COVID Collaborative stated that Black Americans are twice as likely to trust a message if it comes from another Black person.

The CDC’s Office of Minority Health and Health Equity has suggested medical communities should partner with prominent advocacy groups like New Georgia Project, Color of Change, New Virginia Majority and Dream Defenders to acknowledge the Black community’s genuine fears and educate them about the benefits of COVID-19 vaccines.

“I’ve learned a lot from talking to our local African American pastors,” Hess said. “They will tell you things you didn’t know about how the community is feeling about the vaccines. That is what led to the vaccination effort at the Good Shepherd Baptist Church, where the African American ministers had great courage, got up and got vaccinated in front of the cameras.

“That has had a huge impact on getting people in their church to participate in the vaccinations. But we have to continue to improve our relationship with the community.”

Augusta University is also reaching out to more rural areas in Georgia, such as Sardis and Keysville, to promote the COVID vaccinations, Hess said.

“Our medical students are going to go around the state in March and help educate people throughout Georgia about the vaccine,” he said. “The good news about this vaccine is it’s extremely safe and effective. And it works very well in African Americans. What we know so far in the studies, it works as well in African Americans as it does in whites.”

As more variants of the virus emerge across the globe, pharmaceutical companies also have the ability to redesign the existing vaccines to address those new concerns, Hess said.

“I’m a little more worried about the South African variant, but it looks like the vaccines we’re using in this country probably will work against it,” Hess said. “And the new Johnson & Johnson single-shot vaccine was tested in South Africa, so we know it works.

“So, to have all these vaccines is phenomenal. And it’s really important for people to take this because these are super safe. They’re ultra-safe.”

The Medical College of Georgia is determined to help get that message out to citizens throughout the state, Hess said.

“If you don’t do it for yourself, do it for the community,” Hess said, referring to people getting the COVID vaccine. “And that’s what the African American pastors are saying. Do this for your church. Do this for the community.

“And I believe that when the community sees African American pastors getting their COVID vaccination, that’s more powerful than anything I can say.”

Black women die at three times the rate of white women from pregnancy-related causes, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Augusta University and AU Health have been working to address the problem in our community and throughout Georgia, and next in this series, we’ll take a look at the issue and the progress being made.