Editor’s note: “Anne,” who is a participant in the Ryan White Program at Augusta University, has chosen to remain anonymous.

Anne will never forget the day in 1998 when she learned she was HIV positive.

“I was signing up for an insurance policy and they needed to run some medical tests,” Anne said. “A few days later, they called me up and just told me to go see my doctor. That’s how I found out that I was HIV positive. I didn’t have any symptoms or anything. I had no idea.”

As someone who works in the health care industry, Anne was familiar with HIV. She was devastated by the news.

“At that time, even though I was in the health field, I didn’t know whether I was going to live or die,” she said. “I’ve been married since 1985, so when I had to tell my husband, I just didn’t know what to do. At the time, I had children in middle school. So, I had to sit down with my kids and tell them.”

Sharing the truth with her family that she was HIV positive was one of the most difficult moments in her life, Anne said.

“When I told my husband, we definitely had our ups and downs about it. We had some hard times, but there wasn’t any divorce,” she said. “And, even though we’ve been married since 1985, my husband is not HIV positive.”

After telling her family about the diagnosis, Anne also decided to talk to a close circle of friends.

“I told my best friend and I think once you tell somebody that you can trust, it relieves you,” she said. “But I also told a friend that I thought I could trust and she told somebody else. It truly hurt me.”

When you share such personal news with friends, you quickly find out who your true friends are in life, Anne said.

“I discovered this friend was not a friend,” she said. “So, while it hurt me, I had to put on my big girl panties and say, ‘Hey, I’m letting you go. I know who I am. And now I know who you are.’”

While Anne believes there are still a lot of stigmas associated with people who are HIV positive, she says it’s particularly difficult in the Black community.

“People make all of these assumptions about me,” Anne said. “I have never walked the streets and was not doing drugs. But that’s the first thing some people think of when they hear about a Black woman living with HIV in the Black community. But that’s not me.”

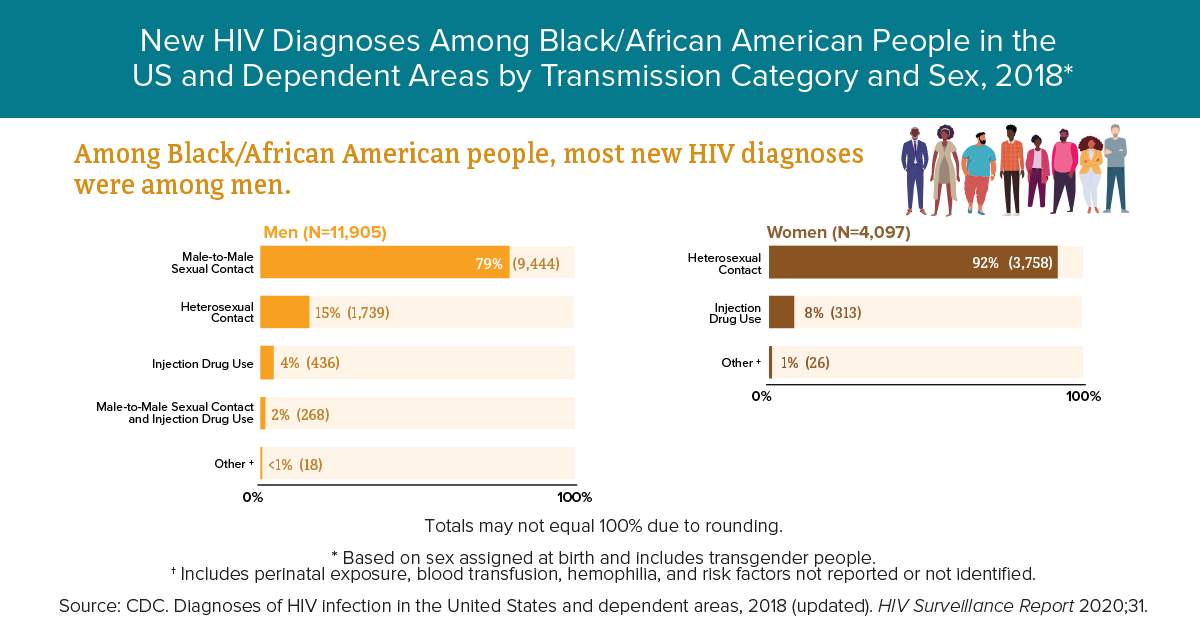

Although African Americans make up 13% of the nation’s population, they account for 42% of the new HIV cases in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In 2018, approximately 16,002 of the 37,968 new HIV diagnoses in the United States were among Black/African American people. Additionally, 27% of new HIV diagnoses were among Latinx communities.

At times, the shame of dealing with her diagnosis was overwhelming, Anne said.

“I was sitting in the house having this pity party,” Anne admitted. “Even though I was going back and forth to work, I was putting on a false face on the outside. But when I got in my house, all I wanted to do was have a pity party for myself.”

Anne realized she needed help dealing with the diagnosis, so she turned to the Ryan White Program at Augusta University.

The goal of the Ryan White Program at Augusta University is to ensure access to health care and reduce disparities to make sure that all people who need care receive it. The program believes that access to high-quality care should be equal, regardless of a person’s ability to pay.

In the program, common problems that are addressed include financial instability, transportation issues, psychosocial issues and the effects of poverty, substance abuse and social stigma. The program also wants to ensure continuity of care and increasing access to comprehensive medical care for underserved, uninsured and low-income individuals.

Anne said joining the Ryan White support group changed her life.

“It built my confidence up with living with the virus,” she said. “As soon as you walk into the Ryan White program, they know you by your name. You’re just not another person that goes to that clinic. You are a person. And that means a great deal to people facing HIV, especially for people who don’t have a support mechanism.

“It lets people know it’s not them just living with this all by themselves.”

Karen Denny, manager of the Ryan White Program at Augusta University, said many of the HIV-related stigmas stemmed from the images that first appeared in the early 1980s.

In 1981, the CDC published a report on cases of a rare form of pneumonia among a small group of gay men living in Los Angeles, which was later determined to be AIDS-related. Shortly after these initial reports, similar occurrences began happening in New York and among intravenous drug users.

By May of 1982, The New York Times ran a story called, “New Homosexual Disorder Worries Health Officials.”

The national newspaper reported this new phenomenon of the immune system had been known to doctors for less than a year, but had already afflicted at least 335 people and killed 136 of those individuals. However, doctors across the nation said the cause was “unknown.”

In 1982, Dr. Bruce Chabner of the National Cancer Institute said that the disorder was now ”of concern to all Americans.” The CDC said it was reaching epidemic proportions and the current total of reported cases probably represented “just the tip of the iceberg.”

It wasn’t until 1984 that the medical community concluded these cases were caused by the Human Immunodeficiency Virus, or HIV.

The virus attacks cells that help the body fight infection, making a person more vulnerable to getting other infections and disease. It is spread by contact with certain bodily fluids of a person with HIV, most commonly during unprotected sex or by sharing injections. If left untreated, the infected individual can develop the Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome, known as AIDS.

But much has changed since the 1980s.

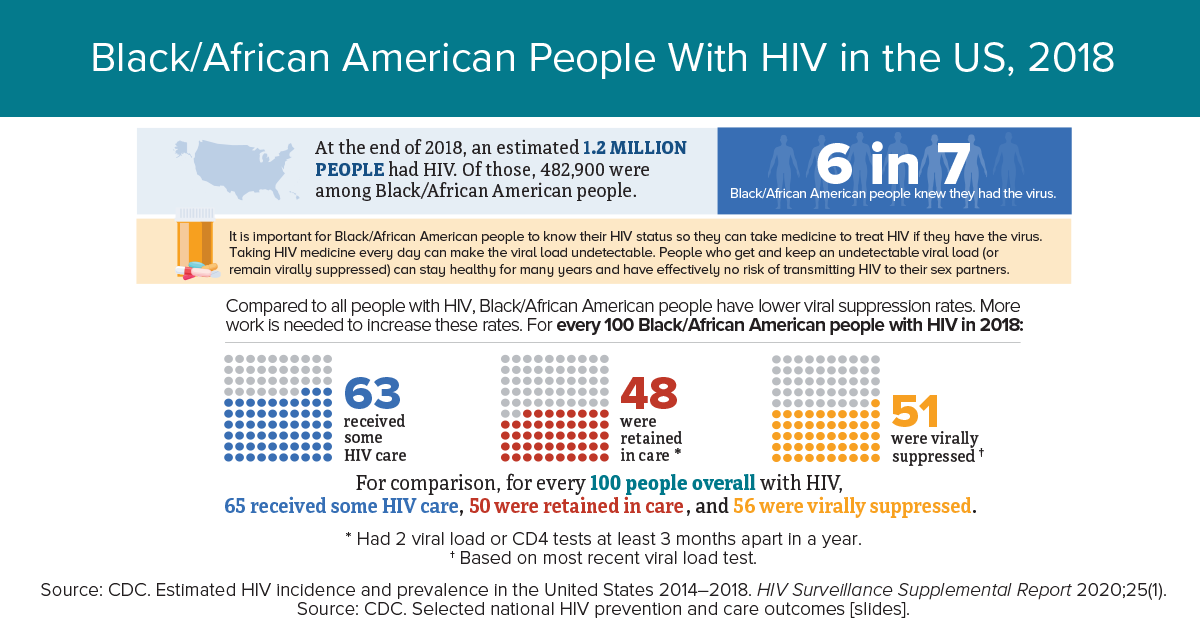

Encouragingly, according to a 2020 report released by the CDC, deaths related to HIV in the United States fell significantly from 2010 through 2018, regardless of sex, age, race or region.

The overall death rate among people with HIV dropped by about one-third from 2010-2018, the November 2020 report stated.

Specifically, the rate of deaths directly related to HIV decreased by 48.4 percent, dropping from 9.1 per 1,000 with HIV in 2010 to 4.7 deaths per 1,000 people with HIV in 2018, according to the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Report.

However, gains among women, African Americans and those of multiple races were much smaller. In addition, people living with HIV in Southern states tragically passed away at double the rate of those with the virus in the Northeast, the CDC reported.

Those living with HIV still face an uphill battle when it comes to people’s views of the virus, Denny said.

“Vulnerable groups who are more at risk of being infected with HIV continue to face others making assumptions about their actual or perceived health status, like their socioeconomic status, sexual orientation and gender identity,” Denny said. “This discrimination can appear in many settings, which often discourages people from getting tested or receiving treatment to avoid being possibly mistreated.”

Denny also said the fear surrounding the HIV epidemic still persists today, despite there being more knowledge now on how the virus is transmitted.

“As long as we don’t address and normalize the treatment of HIV, people will not feel comfortable seeking out the help they need to live healthy lives,” Denny said. “This is why we do our best to make our patients feel at home at AU Health, so they continue seeking care at our facility.”

Many people living with HIV or who are at risk of HIV infection may not have access to prevention and treatment, so when it comes to providing care to patients, AU Health’s Ryan White Program is building trust within the community by bringing HIV prevention to the community, Denny said.

“As a health care provider, you want to jump in and start talking about treatment. However, there are barriers that you have to overcome first,” said Raven Wells, community outreach coordinator for the Ryan White Program, adding that two of the main barriers are lack of knowledge and access to prevention/treatment. “We want the community to know what HIV is and how it is transmitted and we want them to have easy access to prevention services and care.

“So, instead of waiting for people to come to us for help, we use the mobile clinic to bring our services to them so they can access the help they need.”

In addition to using the mobile unit, people living with HIV can receive all of their care at AU Health’s Ryan White Clinic in the Moore Building at 1014 Moore Avenue in Augusta.

In the new 17,150-square-foot building, people living with the virus are able to see their health care provider, a case manager, have their six-month lab draws and see a psychologist. In the near future, those individuals will be able to have their medications filled at an in-house pharmacy and receive dental cleanings and screenings on site, Denny said.

“Our program allows us to provide an overarching, ‘one-stop-shop’ approach of care,” Denny said.

The Ryan White program has been a part of Augusta University for more than 25 years.

It serves more than 1,200 people annually in the CSRA and surrounding counties, including some patients who come from elsewhere in Georgia, Florida and South Carolina.

“Our goal is to provide the ultimate care so they can live healthy lives… And they do,” Denny said. “They can live a normal life, as long as they’re on their medications.”

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, Denny said the Ryan White Program immediately shifted to using a telehealth platform, which enabled nearly 25% of those served to continue getting care and medications.

“We are all about caring for our patients by any means necessary,” Denny said. “We had the resources to continue providing them with medical care so they never missed a beat.”

Among the many services provided at the Ryan White clinic are monthly support group sessions.

Capus Barnett is one of the program’s case managers who conducts the events, and he said allowing patients to talk openly about HIV helps to normalize the subject and correct any misconceptions about the illness.

“I always had a passion to help those with HIV because my family has been impacted by the virus,” said Barnett. “I understand how our patients are already faced with stigmas of having these conditions, and offering them a place where they can share their grievances lets them know they’re not alone on this journey.”

Barnett has been with the program for three years, and he’s making a difference.

“I will never forget the young Black man who came to us after being newly diagnosed with HIV and in need of a job,” said Barnett. “Since we never count anyone out here, we got him started on the proper medical treatments while we worked with him on drafting a resume. I told him to put me down as a reference and he was hired at Augusta University within a few months.”

Currently, there’s a global push to end the epidemic as a public health crisis by 2030. Although the goal is ambitious, Wells said it can be accomplished if the public moves forward with lessons learned.

“I know we can make a greater impact if we continue targeting care to marginalized communities, provide more access to antiretroviral therapies and keep offering HIV prevention and family planning to those at greatest risk,” said Wells. “I am hopeful about our future and this is work we all can do together.”

Due to the tremendous amount of support she has received from the Ryan White Program over the past two decades, Anne said she is able to fully embrace her life and the future ahead.

“A few years ago, I decided, ‘When I turn 50, I’m going to celebrate.’ Then, when I turned 55, I celebrated again,” Anne said, adding she is about to turn 57 years old in a few weeks. “With each birthday, I’m going to celebrate because when I was diagnosed in 1989, I did not expect to be here at 40.

“But here I am. I am a proud, long-term survivor.”