Post-traumatic stress disorder has been a big topic of discussion for decades. However, the way that a negative emotional state — exacerbated by conditions such as PTSD, anxiety, depression and other psychiatric conditions — affects learning and daily life is not well understood.

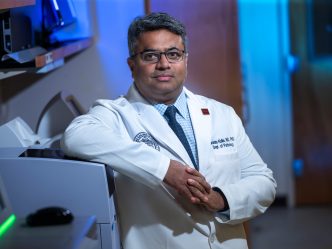

Dr. Almira Vazdarjanova, professor in the Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology at the Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University, recently completed a study indicating that being in a negative emotional state can change the way you learn.

Understanding memories

For over a decade, Vazdarjanova has studied the neurological mechanisms of emotional learning, memory systems in the brain that contribute to PTSD and factors that make people susceptible to the disorder.

“It turns out only a quarter of the people exposed to the same traumatic event will go on to develop PTSD and it’s not understood why some do and some don’t,” said Vazdarjanova.

It all goes to the brain, specifically the amygdala, hippocampus and prefrontal cortical regions. Many researchers have believed the amygdala is where all emotional memories are stored and the hippocampus is only responsible for episodic and factual memories, but Vazdarjanova has found that is not the case. That’s just the start.

“On top of this complexity and myriad of memories, you have emotion and how emotion affects these types of memories and what happens to memories that have an emotional context,” she said. “To induce emotion means something very important happened to that organism. The brain has developed a system in which those memories are better remembered than anything else.”

Vazdarjanova added negative events will be remembered more than positive ones since they induce more stress hormones and activate related brain regions that enhance those memories. Her team, and others, have shown that the hippocampus region of the brain is necessary for the encoding of memories for these events.

Memory encoding requires the expression of some genes to store memories and transfer them from what is learned into long-term memory. Some of these plasticity-related genes have different dynamics of expressions in the cells and can be used to differentiate groups of neurons activated by two separate events.

Earlier studies showed when animals were exposed to the same place at two different times, the hippocampus expressed these genes in largely overlapping groups of neurons, meaning some of the same neurons were expressed in both events. Those rats which were given a shock to their foot in that place during the second exposure had a smaller overlap in the group of neurons expressing these genes.

“It’s not just the place and not just the sensory cues of that place, but what happens in that place is encoded in the hippocampus. We were able to show very convincing evidence the hippocampus is encoding the emotional significance of the place.”

The result of that previous study led to the most recent work by Vazdarjanova and her research team. Their goal was to answer the question, does being in a negative emotional state change the way you learn new information?

New study results

The new project examined this question in rats, who engage learning mechanisms, brain regions and the genes, which are similar in humans. In a controlled environment, they used three events and four groups.

During the first event, rats were exposed to an empty box to see how they would react over a five-minute period. Rats are curious animals, so they explored the box and spontaneously learned about their surroundings.

A second event introduced either a neutral, positive or negative emotional state in three different groups of rats. The rats in the neutral group were exposed to a new box. Those in the positive group were exposed to an identical box, but it contained Froot Loops — sugar induces positive responses in rats, much like in humans. The rats in the negative group were exposed to an identical box, but it contained cat hair, a smell and sensation to which rats are naturally averse.

Then, for the third event, rats were re-exposed to the same “normal” box of the first event. A fourth group only experienced the first and third event with no emotional intervention to control for non-specific disturbances caused by the second event.

“We confirmed with behavior that the intervening event did have an effect on them before we even got to the functional effects in the brain induced by the third event, which had the same physical cues as the first, but they experienced it in a different emotional state,” said Khadijiah Shanazz, a PhD candidate in Vazdarjanova’s lab.

“We created a urine and boli index to infer the intensity of the emotional state we were trying to induce during the second event. In the neutral group, with no emotional intervention, we had a very low index. The same was true in the positive group. But with the negative group, we did see autonomic fear responses indicated by a significantly higher index.”

Importantly, the behavior in the negative group was different during the third event, which was only seven minutes later; this indicates their altered emotional state impacted their experience of an emotionally neutral place.

“The positive and neutral groups were making more crossings of the box and exploring during the third event. The negative group was like ‘No to any of this,’” said Shanazz. “This showed that being in a negative emotional state is having some long-lasting effects on behavior and exploration.”

A measure called the Fidelity Score was also developed to help determine the number of neurons being activated in the first event and how many of those were activated in the second event.

“With the negative emotional state intervening, the Fidelity Score in the negative group dropped compared to the other groups. This means that fewer of these neurons that were activated during the first event were activated during the third event. It’s almost as if they’re perceiving the same place as being more different than the other groups because of the state they are in,” said Shanazz.

“You can see how it directly relates to PTSD. People with PTSD have cognitive difficulties and more often they are in this negative emotional state. Our study provides a clue mechanistically how that happens in the brain. And it’s real,” added Vazdarjanova.

Vazdarjanova also is doing work at the Charlie Norwood VA Medical Center where human studies are ongoing. They have performed a cognitive battery test to evaluate whether they can tell who would benefit from therapy and who wouldn’t, and determine who might have have a lower rate of relapse of PTSD.

“We are convinced PTSD cannot be truly cured. But it can be managed,” added Vazdarjanova. “Part of this management is limiting their negative emotional state and its impact.”

Keeping negative information out of people’s lives can go a long way in how they react.

“Your brain naturally changes over time. So we need to be aware that our brains encode non-emotional information as emotional information when you’re in a negative emotional state,” concluded Vazdarjanova.

Augusta University

Augusta University