A groundbreaking study conducted by researchers in the Vascular Biology Center at Augusta University’s Medical College of Georgia provides the first evidence of why people living with human immunodeficiency virus, more commonly referred to as HIV, are more likely to have hypertension, or high blood pressure.

The NIH-funded research, recently published in Circulation, links hypertension to the persistence of viral protein expression and immune cells – and provides possible ways to counteract the staggering odds.

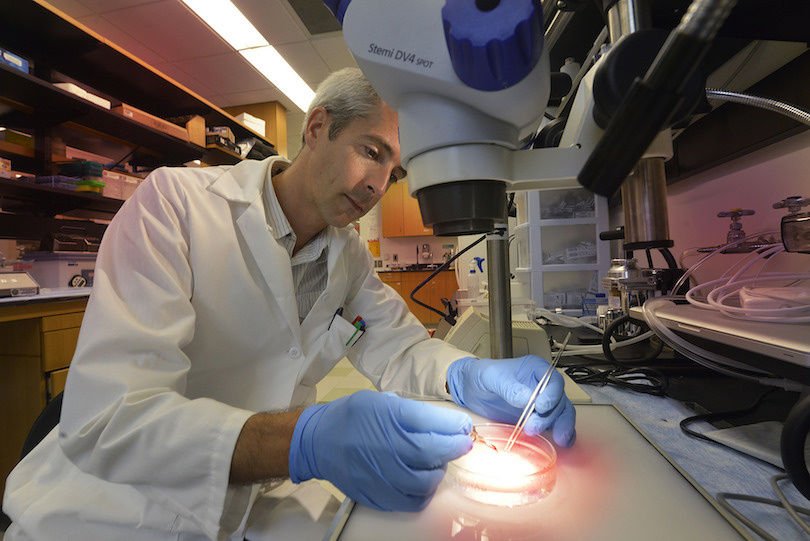

“There are so many publications and literature showing that people with HIV have hypertension, but no one really tried to look into the mechanisms. And being the first to propose a mechanism is kind of really exciting,” said Eric Belin de Chantemèle, PhD, a physiologist and professor in the Vascular Biology Center at MCG and the principal investigator for the research.

The relationship between HIV and hypertension

According to epidemiological studies, up to 68% of people with HIV in the U.S. have hypertension, compared to about 40% of noninfected people.

Often referred to as “the silent killer,” hypertension is known for its usual lack of symptoms and the significant risk it poses for cardiovascular/heart disease, heart failure and strokes. In fact, heart disease is the leading cause of death in the United States, claiming nearly 700,000 lives every year.

“The cardiovascular system is a hydraulic system, and several factors could contribute to an elevation in pressure in this system. In this study, we focused on the blood vessels and the fact that the presence of HIV proteins reduces the ability of the arteries to relax,” Belin de Chantemèle said. “It’s like when you’re using your hose in your yard to wash your car. If you want to have more pressure, you squeeze the hose, and you increase the pressure. With your cardiovascular system, it is the same thing. If your arteries remain in a constricted state, the pressure increases.”

But what causes this spike in hypertension in people living with HIV?

In the last few decades, combination antiretroviral therapy has dramatically lengthened the life expectancy of people with HIV, essentially blocking the virus and rendering it incapable of replicating in the human body. But just because it’s undetectable doesn’t mean it’s gone or completely inactive.

“The issue is that the virus is still there and still able to release viral proteins,” Belin de Chantemèle said. “And we think that those viral proteins that remain in the bloodstream is what is contributing to hypertension and why those people have cardiovascular disease faster.”

![Graphic showing viral proteins and combination antiretroviral therapy contributes to HIV-associated cardiovascular disease. [Eric Belin de Chantemele/Augusta University]](https://jagwire.augusta.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/15/2025/03/1-s2.0-S2452302X21003582-fx1_lrg-1-scaled.jpg)

Testing the hypothesis

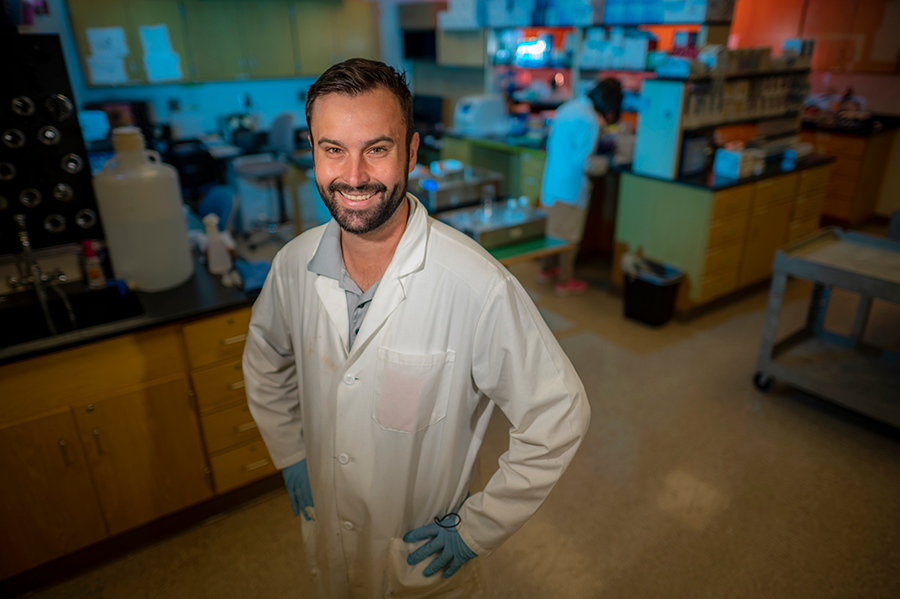

For the experiments, Taylor Kress, PhD, a former graduate research assistant in Belin de Chantemèle’s laboratory and lead author on the manuscript, used genetically modified mice that expressed the viral proteins produced by HIV, mimicking the conditions of people living with HIV on cART. Both the male and female transgenic mice were hypertensive, lining up with his inference that viral proteins contribute to cardiovascular disease.

“We did have preliminary data with the HIV mouse model showing that we had vascular dysfunction and this increase in blood pressure,” Kress said. “So we had point A and point Z; the rest of the points in between is something that I didn’t see coming. I had to follow the breadcrumbs to eventually get from A to Z.”

Because HIV mainly targets immune cells, specifically CD4+ T cells that secrete viral proteins, the team tested their hypothesis two ways. The first was taking bone marrow containing immune cells and viral proteins from the hypertensive HIV-positive mice and giving it to noninfected mice. The second way was taking only CD4+ T cells from the HIV-positive mice and giving them to noninfected mice. The result? Both sets of noninfected mice became hypertensive.

“The advantage of doing experiments in mice is that we can really demonstrate what is causing what,” Belin de Chantemèle said. “Then, with those different manipulations and taking the immune cells from the bone marrow, putting it in a seronegative mouse, we can show that the immune cells are responsible for hypertension. And we could go even further by showing that it’s the CD4+ T cells that are the cause of hypertension.”

How do CD4+ T cells cause hypertension?

While CD4+ T cells are a key component of the immune system responsible for orchestrating immune responses, Belin de Chantemèle explained that not all of them are beneficial for health. Some CD4+ T cells can produce pro-inflammatory cytokines called interleukin-1 alpha (IL-1α), which can negatively impact blood vessels.

The team discovered that IL-1α impairs the endothelial cells that line blood vessels, which are crucial for regulating blood flow and vessel constriction.

“What we show is that IL-1α that is produced by CD4+ T cells reduces the ability of the blood vessels to relax, which increases what we call the resistance to blood flow – total peripheral resistance,” Belin de Chantemèle said. “Then they would be more constricted, leading to an elevation in blood pressure.”

They also learned that when IL-1α interacts with endothelial cells, it increases the expression of an enzyme called NADPH oxidase 1, or NOX1. The expression creates oxidative stress and – you guessed it – hypertension.

Kress hopes this scientific breakthrough will influence other scientists to study IL-1α and what implications it has on bodily functions.

“Not necessarily just in HIV, but in general because it’s a pretty understudied pro-inflammatory cytokine that I think, based on what we’ve looked at with our studies, might be worth taking a look at in different models to see if it’s elevated, see if it affects different pathologies,” he said.

Potential treatments

Based on the findings, Belin de Chantemèle infers steps can be taken to block the action of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1α produced by CD4+ T cells.

There is already an FDA-approved medication that blocks IL-1α receptors and limits inflammation, which may help reduce hypertension. Other inhibitors that would block NOX1 enzymes and possibly have the same outcome are currently going through clinical trials.

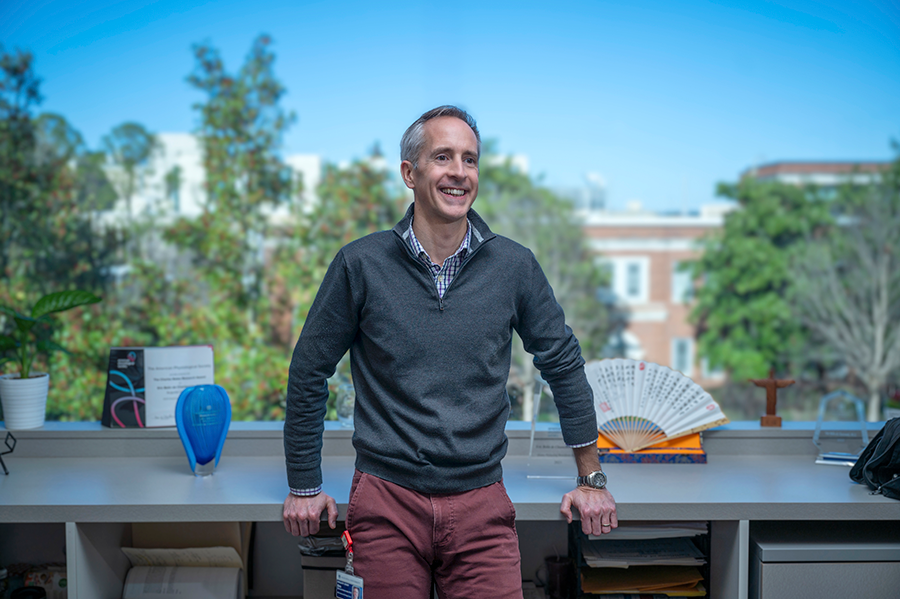

Uncovering the truths behind this ailment and being recognized in a high-tier scientific journal was extremely fulfilling for the team, but the job isn’t finished yet. The publication of this research was a culmination of five years of work, and Belin de Chantemèle and his team have been awarded a $2.7 million grant from the National Institutes of Health to continue their work on the subject for another four years.

He’s also taking on two other NIH grant-funded projects: one with Laszlo Kovacs, PhD, an assistant professor at the MCG Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, to study the correlation between HIV and pulmonary hypertension, and one with Manuela Bartoli, PhD, director of research and professor in the Department of Ophthalmology at MCG, to study the relationship between HIV and retinopathy.

The biggest driving factor for the team is the possibility of their findings being translated over into the medical setting to develop new ways to lower blood pressure for people living with HIV and give them a better quality of life.

“The goal with modern medicine is to try to actually cure HIV, which means completely eliminating viruses that are still remaining in the body,” Belin de Chantemèle said. “But, in the meantime, with the continuously growing HIV population and the fact that it is aging, we have to find ways to prevent the accelerated development of cardiovascular disease that these individuals develop.”

Discoveries at Augusta University are changing and improving the lives of people in Georgia and beyond. Your partnership and support are invaluable as we work to expand our impact.

Augusta University

Augusta University