In 2015, when it dawned on us that watching new Star Wars movies would soon become a holiday tradition, we thought to ourselves: What can we learn from the story behind the stories we love? First published in Dec. 2015, this article, written by a die-hard fan, sought to explore that question. The answers inside, like the messages and meaning behind Star Wars, are timeless.

“I am (not) your Buddha”

A long time ago, in a galaxy not that far away, there lived a clever scholar. His name has since been lost to time.

One morning, said scholar set out for a nearby Buddhist temple, determined to prove his wit.

His goal was simple. He wanted only to beg a question of the temple’s master. The goal was not an unusual one. Villagers routinely asked questions of the local master, and in his wisdom, the kindly old monk did what he could to enlighten them.

But the scholar wasn’t seeking enlightenment. Nor for that matter was he looking for Buddhist wisdom.

His purpose was simpler still. He wanted to test the monk’s resolve, to prove him a fraud.

Arriving at the temple hours later, the scholar bowed before the master. Doing so, he noticed something odd about the man’s appearance. The master carried a staff, a simple wooden walking stick, which he held close to his body. Valuing material objects, the scholar knew, was in clear contradiction of the Buddha’s lifestyle.

The scholar smiled. He had found his in.

When it came time for the scholar to ask his question, he spoke clearly and calmly. “Is it true that the Buddha never denied the prayers and requests of any living thing?” he asked.

“It is,” the master replied.

The scholar smiled. “Then I beg for your walking stick. Will you give it to me?”

Stroking his beard, the master paused to consider the question. “A gentleman scholar would not deny an old man his finest possession,” he said.

Eager to prove his point, the scholar quickly replied, “I am not a gentleman.”

At this, the master laughed heartily.

“And I,” he said, acknowledging his faults as well, “am not a Buddha.”

History may have forgotten the name of the scholar, but today the master is well-remembered among Buddhist scholars the world over. His name is Zhaozhou (or Joshu in Japanese), and his mythic wisdom and playful nature were but a few of the many notable Buddhist influences on one very prominent Western mythology – the Star Wars saga.

Buddhism: The Phantom Message

Looking back, it’s no surprise that master filmmaker George Lucas adapted Buddhist themes into his most successful films. A devout admirer of Japanese director Akira Kurosawa and a self-proclaimed “Buddhist Methodist,” Lucas believed wholeheartedly that there was wisdom in Eastern teachings. He also believed that wisdom could be shared with Western audiences in a noncritical way.

A student of Joseph Cambell, a famous mythologist and the author of The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Lucas admitted from the start that by creating Star Wars, he “consciously set about to recreate myths and the classic mythological motifs.”

Finding the Buddhist themes within those myths, however, can prove tricky.

Such was the case for Dr. Brian Armstrong, assistant professor of philosophy at Augusta University.

While reading an issue of Contemporary Buddhism from 2014, he said he happened upon an article by Christian Feichtinger, a lecturer for religious studies at the University of Graz, which first opened his eyes to the similarities.

“The Jedi engage in zazen,” Armstrong said. “I’d never before thought about that. As a part of humanities, I teach Dogen, who is responsible for giving zazen, or seated meditation, primacy in Zen Buddhism.”

Dogen, the founder of the Soto school of Zen Buddhism, popularized zazen in the early 13th century.

In recent decades, the image of the silently meditating, cross-legged monk has become almost synonymous with Buddhism in the West. In part, that’s why Armstrong believes Lucas borrowed the idea of zazen as a trait of the Jedi.

“Images of zazen immediately invoke Jedi values,” Armstrong said.

In his article, “Space Buddhism: The Adoption of Buddhist Motifs in Star Wars,” Feichtinger expands upon Armstrong’s sentiment by stating that “Lucas uses the distance of Asian and Buddhist culture to the Western world to also enact the Jedi as the Other …”

Like the practice of zazen, the majority of Buddhism’s perceived “Otherness” comes from a much larger and much more storied Buddhist tradition of spurning creature comforts and forsaking earthly ambition.

Zazen, when successfully performed, is a means of doing both. But what is the key to successful zazen? According to the master himself, the answer is simple: Not thinking.

“Sitting fixedly, think of not thinking,” Dogen explains in the Kana Shōbōgenzō, a collection of his teachings. “How do you think of not thinking? Nonthinking. This is the art of zazen.”

There’s an inherent struggle in striving to achieve serenity through “nonthinking.” The key to that struggle is the word “striving.” After all, how can one break free of desire without first desiring to end the desire? And how does one come to that conclusion without first thinking?

This paradox, Armstrong said, is often referred to as the Paradox of Desire.

“In Buddhism, there is a desire to achieve nirvana, to become awakened and enlightened,” he said. “But consciously desiring to achieve nirvana prevents you from doing so. The result is that those who try find themselves locked in suffering forever.”

Images of Darth Vader spring to mind. A gifted child perpetually frustrated with his inability to obtain the same Buddha-like respect and wisdom his teachers have attained, he is eventually driven to despair in his search for inner peace.

He is locked in suffering, incapable of achieving enlightenment.

Or was he?

According to Armstrong, Dogen rejected the notion of transcending beyond human suffering as a means of enlightenment. Instead, he said, Dogen posited that for a Bodhisattva, a being destined to achieve enlightenment, the goal was to try bringing others to enlightenment through compassion.

That sentiment, too, can be found in the Star Wars universe.

We see it in Luke, redeeming his father. We see it in characters like Lando Calrissian and Han Solo, both of whom are eventually brought to the light by compassion.

But most of all, we see it in the Jedi Masters.

“It’s hard not to think that the concept of the Bodhisattva was an influence on the Jedi,” Armstrong said. “For example, we see that despite Obi-Wan Kenobi’s transcendence, he chooses to remain a part of the physical world to continue helping Luke achieve his enlightenment. That compassion is central to Dogen’s notion of the Bodhisattva.”

But if Obi-Wan Kenobi is the model of a Buddhist compassion, then another central figure in the Star Wars universe takes the term “Bodhisattva” to an entirely different level.

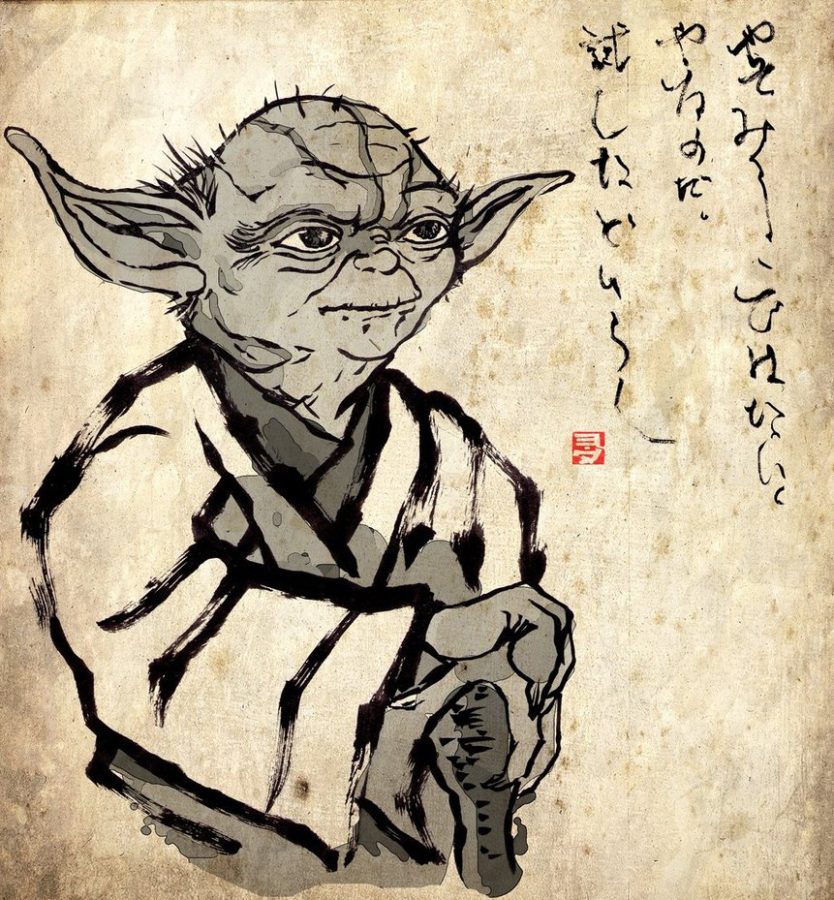

The Little Green Buddha

In the Star Wars universe, perhaps no other character embodies the values of Buddhism more than Master Yoda.

The reasons why are plain to see. Yoda’s small, somewhat comical appearance makes him immediately nonthreatening. The first time we meet him, his strange, playful manner of speaking brings to mind the wisdom of past sages like Zhaozhou and Dogen, men more than willing to admit their faults in the pursuit of enlightenment. The little hermit wants for nothing, and unlike Luke, Yoda seems to thrive in an environment that is hostile to all other creatures. He belongs and doesn’t simultaneously.

He is, on the surface, a tiny green version of the Buddha himself.

But Lucas’ intention of envisioning Buddhist values in Star Wars goes far beyond Yoda’s personality and physical attributes.

In addition to being a master of the Force, the Buddhist scholar quickly realizes that Master Yoda is also a master of koans.

“Koans are short, paragraph-length stories about encounters between Buddhist monks,” Armstrong said. “The most famous example of a cliché koan is the question, ‘What is the sound of one hand clapping?’”

It’s a confusing question, but in a way, that’s the point. The purpose of the koan, Armstrong said, is to stymy thought by creating a mental paradox.

“Koans generate a paradox in the mind of the listener,” Armstrong said. “That paradox, in turn, is caused by the listener’s perception. The purpose of a koan is to help listeners to think better by removing obstacles to their perceptions.”

At first, listeners might be inclined to think about the actual sound of one hand clapping. The purpose of the koan, however, is to change the listener’s perception. One hand obviously can’t clap, therefore, the answer to what sound one hand clapping would make is silence.

Yoda poses a similar paradox to Luke in The Empire Strikes Back, when Luke, preparing to use the Force for the first time, says, “All right. I’ll give it a try.”

“No! Try not!” the little Jedi Master famously exclaims. “Do or do not. There is no try.”

It quickly becomes apparent that what Yoda is asking Luke to do is impossible. Whether one succeeds or fails at a task, there is no way to do something without first trying.

His purpose isn’t to discourage his apprentice, but rather, to focus Luke’s mind on the present.

Feichtinger points out that Yoda uses this technique several times through the series. Another well-known example also comes from Empire, when Luke asks Yoda about the nature of the force.

“But how will I know the good side from the bad?” Luke asks.

“You will know. When you are calm. At peace. Passive. A Jedi uses the Force for knowledge and defense, never for attack.”

“But tell me why I can —”

“No! There is no why …”

As an audience, we recognize that something is wrong with Yoda’s statement. Of course there’s a why. There’s always a why, but for the sake of staying focused in the present, he poses a paradoxical statement to center his apprentice’s mind.

In addition to showing his mastery of the koan, Yoda touches upon another Buddhist notion in the same montage: the interdependence of all things.

“… my ally is the Force, and a powerful ally it is,” he says. “Life creates it, makes it grow. Its energy surrounds us and binds us. Luminous beings are we, not this crude matter. You must feel the Force around you; here, between you, me, the tree, the rock, everywhere, yes.”

Armstrong believes Dogen would agree with Yoda’s philosophy.

For, just as nothing is separate from the Force, Dogen believed that nothing could escape from the cycle of death and rebirth.

“Dogen rejected the notion of duality,” Armstrong said. “He believed there was only this plane of existence and that all things in it were interconnected and incapable of escaping karma.”

Whether taught through koans or the act of meditation, it becomes clear that Dogen and Yoda had a message to share. At its core, it was a message Lucas shared with millions of viewers around the world.

“We all have good and evil inside of us,” Lucas stated in a 1999 interview with Bill Moyers. “ … We can choose which way we want the balance to go.”

In that way, all three “masters” achieved the same goal.

They each succeeded in shaping the lives of others.

Plato’s (Old) Republic and the power of film

Shaping lives, and by default, shaping societies, is an ancient concept.

In his Republic, Plato states that the two are irreversibly intertwined, that the city (society) and the soul (the individual) are forever tied to one another’s fate.

A just city, Plato believed, would create just citizens, just as righteous citizens would produce a righteous city.

“The stories that you tell a child stamp the notion of ‘the Good’ on a child,” Armstrong explained. “Good media will raise good children. Bad media will raise bad children.”

Knowing that, Lucas faced a tremendous challenge.

As difficult as translating a Buddhist message to a Western audience was, translating it via film would prove an entirely different beast. Especially in the form of a science fiction summer blockbuster.

“Back then, summer blockbusters were a brand new concept,” said Matthew Buzzell, assistant professor of communications and award-winning documentary filmmaker. “Jaws was really the first, back in ’75.”

According to Buzzell, few people at the time expected a science fiction movie to have any kind of relevant impact on the film industry, let alone the same impact as Jaws. Fewer still expected Star Wars to be the movie that eventually topped it.

The success was especially strange considering that Star Trek, a sci-fi success in the 60s, had already been cancelled by the 70s.

“Science fiction in the 70s was the realm of B-movies,” Buzzell said. “Star Trek had a cult following in ’77, but there was this collective knowledge that it had been canceled. Science fiction was kind of marginalized as a result.”

Sci-fi was, in a sense, “Bad” media.

Rick Pukis, assistant professor of communications, said he saw the original Star Wars as a child. He said he walked into the theater not knowing what to expect. What he saw, though, changed his perception of film.

“It knocked my socks off,” he said. “I’ll never forget when that first starship flew across the screen.”

Today, both men work together to produce Augusta University’s Cinema Series, a semester-long film series that offers students, faculty, staff and members of the community opportunities to explore rarefied films not found in local cinemas.

They said part of the inspiration for the Cinema Series was to share the feeling of seeing a movie on the big screen, in the dark, with no distractions. It’s a feeling both professors said they experienced while watching the original Star Wars. It’s also one of the traits of a respectful society.

“Your viewing environment is important,” Pukis said. “When I was teaching in Paris, the theaters there were entirely dark. There were no lights on except for the projector. There were no rattling bags, no popcorn crunching. It was just a pure cinematic experience. Everyone enjoyed it.”

Buzzell said he remembered there being few distractions during the movie. Admittedly, though, he said he was enthralled by it at the time.

“I remember people standing to applaud when the Death Star exploded,” he said. “I’d never seen anything like it.”

Both Pukis and Buzzell recalled being fascinated by Star Wars for the movie’s storytelling and visual effects. Armstrong said he had a slightly different interaction with the first movie.

“There was this sense of longing, seeing Luke looking off into the desert,” Armstrong said. “Something about that message resonated with kids in the seventies. It had this sense of saying ‘something great awaits you.’”

For all three men, Star Wars was more of an experience than a movie. Though all three saw the original Star Wars as children, they remember it well to this day.

“It was a different time,” Buzzell said. “Star Wars truly was a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away, and for me, that galaxy was Augusta, Georgia, in 1977.”

Today, the world is a slightly different place. With the course of world events changing by the hour and the perpetual threat of harm looming over our heads, it’s easy to forget the lessons Star Wars had to teach us.

This holiday season, as you read the headlines, try to remember some of that past wisdom, whether you take it from George Lucas, J.J. Abrams, or from the Buddha himself.

Do, or do not. Ask why, but never at the expense of the future. Be wise. Be mindful.

But most of all, be compassionate.

May the Force be with you.

Always.

Augusta University

Augusta University