Dr. Jennifer Bradford had a problem.

Without healthy microglia, her research into a notoriously aggressive brain cancer would stall.

“You can’t get data from a half-dead cell,” said Bradford, assistant professor of biology in the College of Science and Mathematics at Augusta University.

Scientists across the country have published protocols for dealing with microglia, difficult-to-study immune cells in the brain that are thought to interact with tumor cells, but they were unreliable.

“The cells were either dead on arrival or died shortly in culture,” Bradford said. “The few that lived looked awful.”

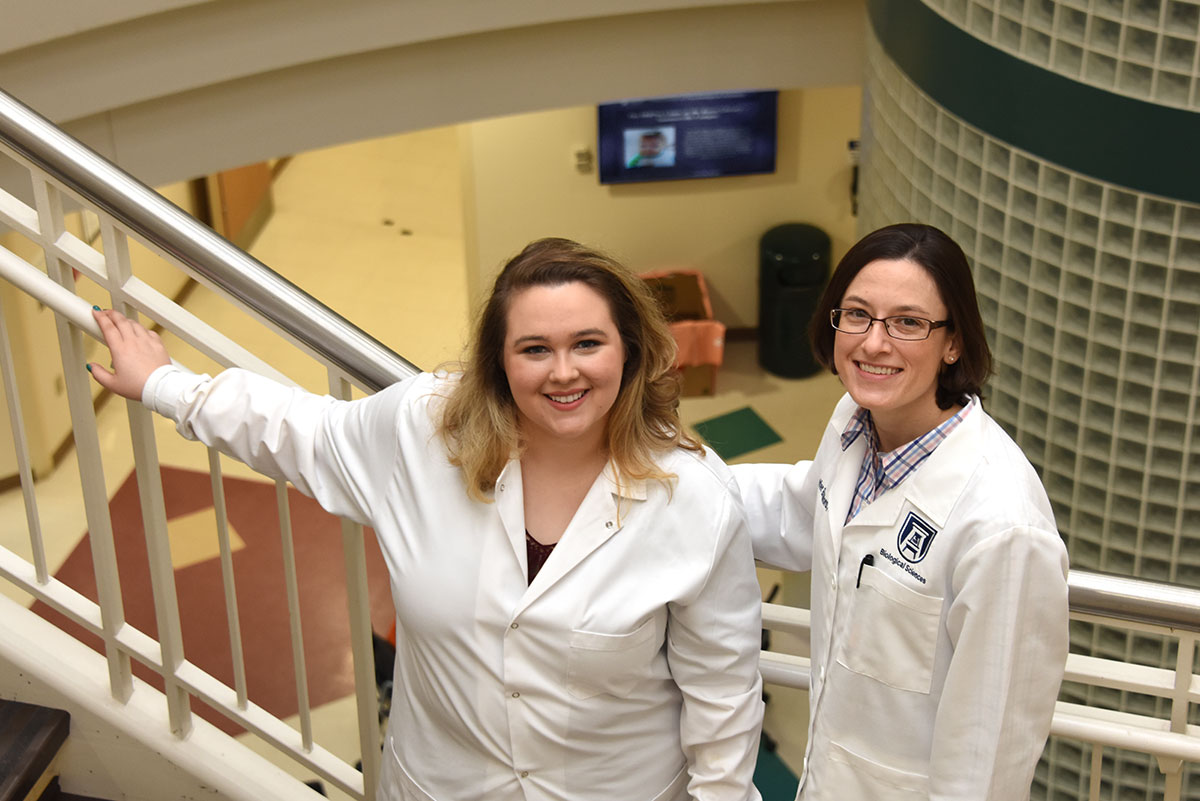

Her solution? An undergrad. Specifically, an undergraduate student named Deanna Doughty.

Now a senior, Doughty joined Bradford’s lab as a sophomore in 2016.

“We had this overarching hypothesis about microglia in the cancer environment,” said Doughty, an Honors student who dedicated her thesis to this problem. “My project started with, ‘How do we get these cells from a mouse and get them to live in the lab?’ It was a process.”

By “process” Doughty means two years of experimentation and optimization, two years of trying and failing, two years of arriving at the lab only to find that the cells she had isolated the day before hadn’t lived overnight.

The lab needed this to work. Future experiments depended on it. Whatever isolation protocol they settled on, they had to be able to repeat it over and over again during the next phase of research.

“We got to the point where it was really optimized, but we weren’t getting enough cell yield and the cells we were getting were dying in culture,” Doughty said. “We scratched that idea and looked at other options.”

Rinse and repeat.

For two years.

Little is known about glioblastoma.

Also known as glioblastoma multiforme or GBM, it’s a difficult to diagnosis, difficult to treat and difficult to study brain cancer. A diagnosis is almost always a death sentence.

“Lifespan is usually about 12 months or two years, max,” Bradford said. “Some folks are diagnosed and they’re gone in a month. It’s just horrible.”

It’s been in the news following the deaths of high-profile men, like Senator John McCain and former vice president Joe Biden’s son, Beau, both of whom died of the disease.

Bradford was introduced to glioblastoma research by Dr. Ali Arbab of the Georgia Cancer Center, where she’s also a member of the Cancer Immunology, Inflammation and Tolerance Program. Before coming to Augusta University, she studied an immune-signaling pathway called NF-κB in breast cancer. She’s now looking at that same pathway in glioblastoma.

“We find that in many cancers, the NF-κB signaling is activated. It’s true for breast cancer,” Bradford said. “We’re finding this signaling pathway activated in – the list just goes on – pancreatic, prostate, lung and brain cancers.”

Glioblastoma spreads so aggressively because the cancer cells recruit non-cancerous immune cells to the tumor. The more immune cells that get recruited to the tumor, the worse the prognosis for the patient.

“These immune cells, they’re not cancerous. They should be attacking the tumor cells but they’re not,” Bradford said. “They’ve been recruited and somehow their normal function has been hijacked so they no longer kill the cancer cells. Instead, they promote the tumor.”

Along with Arbab’s group, Bradford has designed new research studies on glioblastoma to study this phenomenon.

“We have evidence that if we delete the NF-κB pathway, these cells become less tumor promoting and we’re wondering in a GBM environment whether that might be the same,” she said.

To find out, however, she’d have to successfully isolate microglia. It’s why, in 2016, Bradford wrote to Dr. Tim Sadenwasser, the director of Augusta University’s Honors Program, to enlist the help of a student.

“I said, I want someone who’s going to be able to commit and really focus,” she said. “They’ve got to be nice, hard-working, diligent, conscientious and motivated.”

He sent her Doughty. She was all of those things and more.

“Most students are not prepared for the amount of training required,” Bradford said. “It’s extensive. Deanna didn’t scare. It was a good fit.”

Bradford requested an Honors student because of the exceptional time commitment involved.

“Some students really just want a lab experience. They want to get in and see how research goes but they’re not necessarily wanting their own project. For an Honors project, you have to dedicate enough time to see it through,” she said. “That’s why I asked Dr. Sadenwasser to send me an Honors student. We had a big problem that we needed to be solved. I needed someone diligent enough to focus on it.”

Doughty wasn’t familiar with glioblastoma or a lot of other things she’d be asked to do when she got the invitation to dive head-first into research.

“I was a little bit nervous,” she said. “A lot of the stuff we were doing I had never heard of. We were looking at a specific cellular pathway I had never heard of.”

But Bradford was encouraging and Doughty decided to “go with it.”

Doughty was eager to get involved. As a cell and molecular biology major with a minor in British literature, Doughty has her sights set on medical school and hopes to eventually become an emergency room physician.

“It’s almost become a staple of the pre-med track,” she said. “I think research really sets applicants for med school apart.”

An Augusta local, Doughty originally considered going away for school. “Then I thought, ‘Why would you leave?’ I realized it was the best place for me. That’s when I applied, because there are a lot of options here with research, making connections and networking that I wouldn’t get somewhere else.”

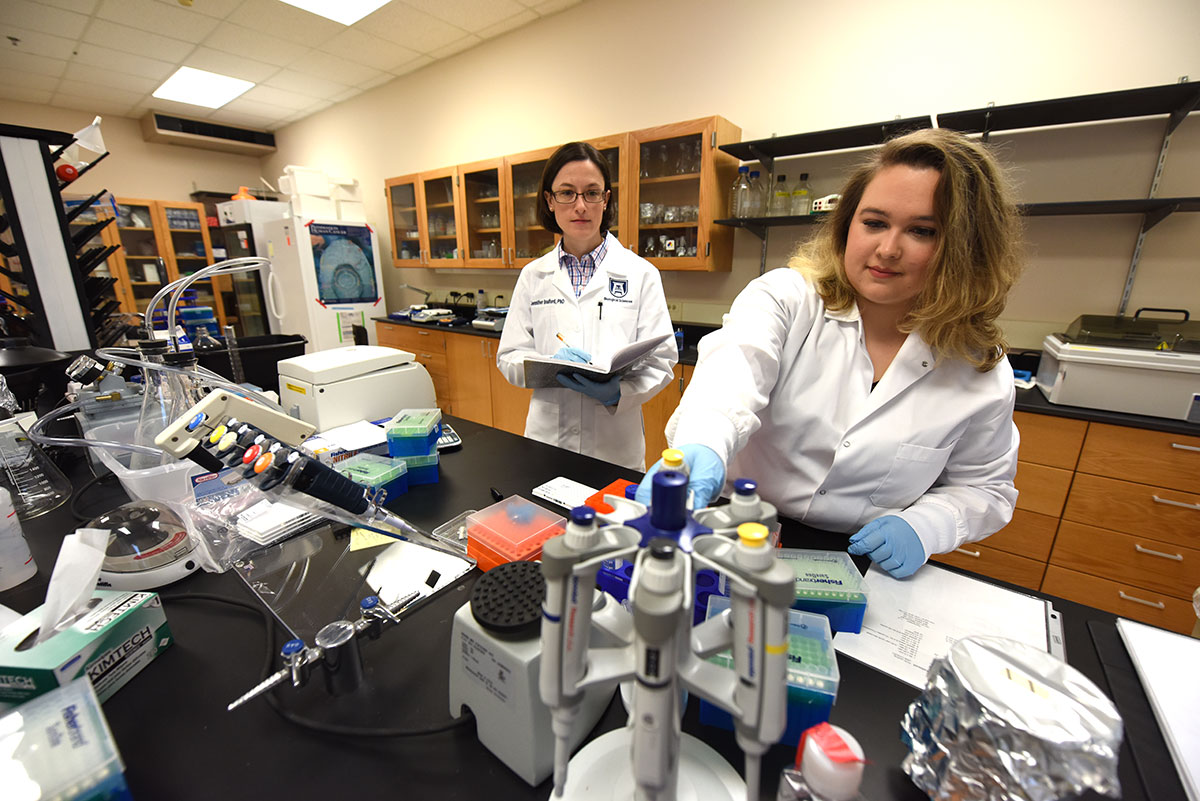

It wasn’t long before the lab became Doughty’s home and Bradford her mentor.

“I feel like the lab is kind of my home, which I think is a different experience for an undergrad,” Doughty said. “Being so connected and integrated into the lab is special.”

Bradford agreed. “Deanna has functioned more as a graduate student than as an undergrad,” she said. “She’s had the whole experience. She’s learned not only techniques, but she’s really learned the perseverance required to optimize a very complicated protocol. It’s pretty rare.”

At some larger schools, undergrads tend to be dishwashers, maybe only meeting their faculty research mentor a handful of times. But, at Augusta University, the Department of Biological Sciences has a long history of mentoring undergrads.

“We know how important it is to the education of a science student,” she said. “It’s one of the things that drew me here — the opportunity to work one-on-one with undergrads in the lab. It’s a part of the culture.”

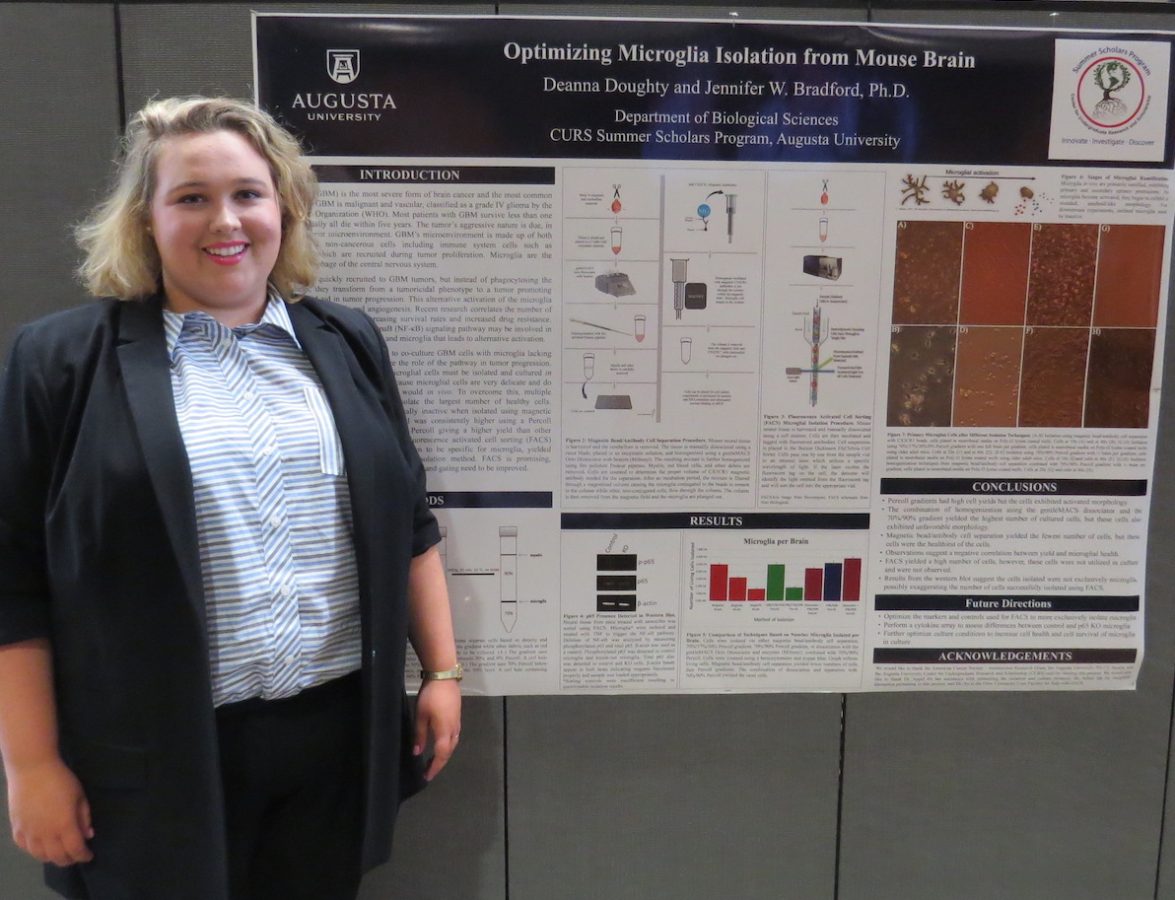

In all, Doughty estimates she’s spent 400 hours in Bradford’s lab. Two hundred of those hours were funded through Augusta University’s Center for Undergraduate Research and Scholarship Summer Scholars Program.

The program provides an intensive 9-week research experience with funding to support student-faculty collaboration.

“What we provide is an opportunity to focus,” said Director Quentin Davis. “With that stipend, the students don’t have to rush off to another job or to class. Their live, hands-on experiences accomplish learning in real time. Even as an undergraduate, they can focus as they would later in their careers, working one-on-one with faculty mentors, which is key.”

The faculty-student relationship is truly collaborative.

“You have that intimate exchange of ideas and questions,” Davis said. “Faculty may provide a jumping off point, but it’s truly a collaborative effort with students. It’s a more professional and relaxed relationship.”

“My lab is fueled by undergrads,” said Bradford, who currently has eight undergraduates working under her direction. “They are the backbone of the lab.”

Bradford is a mentor to them all, Doughty said.

“She never misses an opportunity to teach her students more about science and why we do what we do in the lab,” she said. “To her, research is more than just going through the motions and accomplishing a goal.”

The relationship with a close faculty mentor like Bradford has been really meaningful, Doughty said. “My research experience would not have been what it is under the guidance of a different mentor.”

[brand-timeline]

The days were long and progress was slow.

Throughout 2016, then 2017, and well into 2018, Doughty continued trying new techniques, often with Bradford’s recommendations or the help of other students. She’d try something and it’d fail. Bradford would remind her scientific progress depends on failure.

“So many students get really discouraged when they get negative results. The students who stick with it, like Deanna, are ultimately the most successful,” said Melissa Knapp, CURS coordinator who has worked with Doughty for two summers. “You can see it in her work and just from meeting her, how driven she is.”

It was exhausting, thrilling work, with different challenges every day, Doughty said. Some methods took eight to 10 hours a day. Others only six. More often than not, she had to break the work up into phases she could fit between classes.

“I’d prepare the isolation the day before or a couple days before, then come in and do the isolation. I’d come back and check the cells the next day, change the medium and then observe the cells over the next few days,” Doughty said.

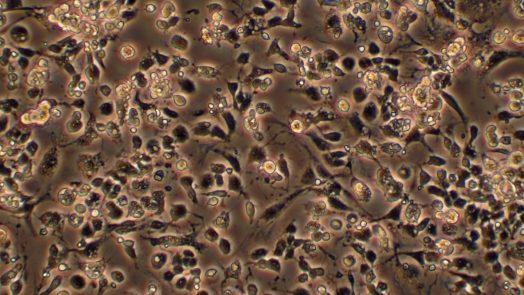

Finally, one day this past Fall, Doughty arrived at the lab and saw something she hadn’t seen before: healthy, living cells.

“I was so happy I think I cried,” she said. “At first it was just, ‘I’ve got cells,’ which was amazing.”

It was August 24. A day later, McCain died. The urgent need for new glioblastoma research began making headlines.

Doughty was so proud that she took a photo of her cells through the microscope and downloaded it to her iPhone.

“I’m that nerd,” said Doughty, who still carries the photo of “her” cells on her phone like photos of a newborn baby. “I show people, ‘Look. These are my cells.’”

After two years, they finally had created an isolation protocol that resulted in healthy cells. Because of Doughty’s work, new experiments could begin in Bradford’s lab, inching researchers closer to an understanding of what happens in the brain when cancer cells hijack otherwise healthy immune cells.

But that’s not all.

Doughty’s method, which she’s currently writing for publication, isn’t just significant for Bradford’s lab. It has the potential to help scientists studying Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, Autism or other disorders and diseases in the brain.

“That’s why this is really important. Working with microglia is hard. Not a lot of people do it. These cells are delicate. They’re hard to isolate, which we found out first-hand,” Bradford said. “Hopefully having this protocol will help other groups advance their studies.”

After the breakthrough, Doughty immediately began optimizing the protocol. She also prepared a presentation on her work for the 2018 National Collegiate Honors Council Annual Conference in Boston.

While she’ll travel and publish – two amazing benefits – Bradford said Doughty walks away from her lab experience with another advantage.

“It’s real research,” Bradford said. “You cannot get that in a lab course. In a lab course, your experiments are designed to work.”

Not so in a real, working lab.

“Deanna found out first-hand what real science is like. Published techniques just weren’t working. So, she had to figure out what she needed to do to get it to work. She spent two years answering that question and she finally got a product, which I think, some students will not get that satisfaction of having it work,” Bradford said. “Science is a delayed gratification field.”

As for Doughty, she’s proud her persistence paid off.

“It’s awesome to be able to contribute to the body of knowledge that’s out there. It’s awesome to be able to say I did this,” she said. “I did something that was significant in the field, not just as an undergrad, but in the field, to science.”

Student Research Seminar

Hear Deanna Doughty’s research in her own words at a Student Research Seminar April 19 at the Jaguar Student Activities Center on Augusta University’s Summerville campus.

Augusta University

Augusta University