Hope House saved Amber Wilhelm’s life from an opioid substance use disorder. The Augusta Area Comprehensive Offender Re-entry Program developed by Drs. Aaron Johnson and Lufei Young aims to help more women like Amber find their future through recovery.

Finding the Light

The line between healing and grieving is needle-thin. Thinner perhaps for those in recovery. Like grieving, healing a chemical dependency comes in stages, the steps—familiar to anyone who has lost something dear—often springing up from the dark like mile markers on a moonlit trail. First come the animal pains, the unfiltered emotions. Denial (“I don’t hurt”). Anger (“I hurt because someone made me”). Then come the darker pangs, the lingering aches. Things like bargaining (“I’ll do anything to make the hurt stop”) and depression (“Will it ever go away?”).

Things like guilt.

Acceptance, when it finally comes, rolls along an hour or so before dawn. Many never find it. They either get turned around or wander off the path completely. Others, afraid or perhaps even unable to begin, find themselves tripping over every broken branch, every jagged stone, grasping for a light they can’t quite see and don’t quite believe in. That was nearly the case for Amber Wilhelm.

At the age of 25, Wilhelm had hit rock bottom. Raised almost as an afterthought, she’d grown up a victim of abuse and substance use disorders, becoming addicted to opioids at an early age. She’d learned to cope with addiction—her family’s and her own—the way most children do in troubled homes. She lashed out. She put up walls. She locked away her true self. Unchecked, her pain manifested as a set of secondary emotions. Anxiety. Self-loathing. Rage. (Her temper, as her former counselors will attest, is legendary.)

Out of jail with no place to go and a toddler on her hip, she had all but given up on herself. Then a court mandate brought her to Hope House—a long-term residential treatment facility for women living with substance use disorders and mental illness.

The experience changed her.

“I didn’t want to be here,” Wilhelm, now 28, says, admitting in the very next breath that Hope House saved her life. But the journey wasn’t an easy one.

[mks_pullquote align=”left” width=”300″ size=”24″ bg_color=”#ffffff” txt_color=”#003359″]“I cried every day. But I needed that. There was healing in those tears. There was healing in every slammed door.”[/mks_pullquote]

Growing up in an abusive home, she had learned to mask at a young age. Burying herself in makeup, she would hide, day after day, convincing herself that if no one could see her true face, no one could see her pain. “I would put on a bunch of makeup and it was just like—I didn’t want to be vulnerable,” she says. “You couldn’t mess with me.”

Early on, a counselor noticed the habit and confronted her about it.

She said, “You know, every time you have a hard trauma group, the next day you put on a bunch of makeup.” Not long after, counselors took away all of Wilhelm’s makeup. When her behavior worsened, they also took away her phone and recommended she not go “on pass”—meaning off-campus—for the weekend. Little by little, the counselors at Hope House stripped Wilhelm of her fragile defenses, tearing away the fall backs and empty comforts that had for so long rooted her life in tragedy. In doing so they made her more vulnerable than she’d ever wanted, or ever allowed herself, to be.

“I cried every day,” she says. “But I needed that. There was healing in those tears. There was healing in every slammed door.”

Nearing the end of her 6-month mandated stay, after countless shouting matches, one broken window—her son, Amari’s, doing—and more slammed doors than she could ever hope to count, Wilhelm sat back and reflected on those experiences and the deeper truths they’d helped her discover about herself.

“When I was honest, I said, I’m not ready [to leave],” she says. “That’s what I tell the girls now. Be honest with clinical. Let them know you’re not ready. Let them know you fear getting your kid back right now, that you still need to work on some things.”

This Disease Wants Us Dead

Seated beside Karen Saltzman and Madison Bentley, Hope House’s executive and clinical directors respectively, Wilhelm smiles, biting back a yawn. She works nights now. Third shift. And though the work is rewarding, nothing beats a long nap on a warm afternoon. Her eyes, warding off the constant creep of sleep, shine with an almost infectious vibrancy. She’s a new woman. She has Hope House to thank for it.

“When I got here, I had just left—” she begins only to pause, the breath catching in her throat. “I got kicked out of another treatment center.”

Things were different at Hope House. The people were different.

Having joined the nonprofit as executive director in 2008, Saltzman has seen the full spectrum of substance use disorders. She’s also seen the harrowing impact addiction can have on women. Especially young mothers.

In her first year at the facility, she’d been approached by another young woman. A mother, also new, who had been living with substance use for years. She was desperate. Most of the women who end up at Hope House are, but this case was different. The disease—the American Medical Society recognizes addiction as a mental illness—had taken a toll on this young woman, and on her family. Having recently given birth, she’d come to Hope House with her infant to find her way out of addiction.

To seek a light of her own.

[mks_pullquote align=”right” width=”300″ size=”24″ bg_color=”#ffffff” txt_color=”#003359″]“That experience taught me more than anything I could have ever learned from a workshop or a lecture. That woman loved her baby. I know she did. But this addiction is so strong. I knew, in that moment, this was bigger than I ever imagined.”[/mks_pullquote]

She caught a glimmer of it during her brief stay. At least, Saltzman hopes she did. The Hope House of 2008 is a far cry from the Hope House of 2018 in terms of treatment options, but even before the facility shifted its focus to a more individualized care model, there was light to be found, and if that young mother found it, she held on to it for as long as she could. She must have watched it fade, hour by hour, like her own personal sun, setting behind half-opened blinds. Like healing, succumbing to a chemical dependency also happens in stages.

Night fell.

“I can’t stay,” the young woman told Saltzman one afternoon, clutching her newborn to her chest. “I have to leave.”

Saltzman begged her to stay, reassuring her there was a place for her at Hope House. A place for her child. After a moment’s thought, the woman, a mother who had come seeking help, seeking hope, handed Saltzman her baby and headed for the door. “I’m not taking the baby,” she said.

At that point in her career, Saltzman had been working in nonprofits for nearly two decades. She’d helped the homeless, explored various behavioral health settings, and in all that time, never had she witnessed a force strong enough—or malicious enough—to tear a mother from her children.

“That experience taught me more than anything I could have ever learned from a workshop or a lecture,” she says. “That woman loved her baby. I know she did. But this addiction is so strong. I knew, in that moment, this was bigger than I ever imagined.”

The most terrifying thing about addiction, perhaps, is not how powerful it is, but rather how very close we are to the brink of it at any given moment.

Dr. Aaron Johnson, interim director of the Institute for Public and Preventive Health at Augusta University, has studied substance use prevention and treatment 24 years. In addition to his research, he and other faculty members throughout the university also guide up-and-coming health care professionals through Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) training. The training, which encourages individuals to speak candidly with their health care providers about substance use behaviors, is difficult to master. It requires empathy and active listening. And it’s needed now more than ever.

“[SBIRT] allows you to identify people who are using substances in a way that is unhealthy but who are unlikely to show up at an addiction treatment facility,” Johnson says. “People for whom a brief intervention is sufficient to curb dangerous behaviors.”

The man who has one too many drinks after dinner. The woman who takes an extra pain pill, but only when her bad knee’s really bothering her. For those at risk of developing a substance use disorder, one of the most effective treatment methods could be a candid, empathetic conversation about the behaviors that place them at risk.

“Those people account for about 20 percent of the adult population in the United States,” Johnson says. “Screening in healthcare settings can also identify another 5 percent with a substance use disorder who need additional intervention.”

The numbers are no surprise to Wilhelm. While that figure includes a wide range of substances—including alcohol, narcotics and opioids—the looming threat of addiction and the hold it has over individuals living with substance use disorders would be terrifying no matter the percentage.

“My probation officer used to tell me, ‘You either want life or you want death,’” she says. “Because this disease wants us dead.”

Clearing the Path

The moment a woman walks through the front door at Hope House care is given.

“If she’s thirsty, we’ll get her a bottle of water,” Saltzman says. “If she’s hungry, we’ll go to the kitchen and make her something to eat. If her clothes need washing, we’ll find a couple of quarters and help her get them washed.”

If a woman asks for treatment, or in Wilhelm’s case, is court mandated to seek it, the formal intake process begins. The first step is assessment. Crucial to helping a participant develop her treatment plan, the assessment helps the clinical team determine immediate and long-term care needs. Then, barring any immediate crises, the participant is assigned a case manager who helps her navigate the campus rules and initial paperwork. Afterward, she receives a further nursing assessment, followed by an appointment with a psychiatrist.

In the morning, it’s off to life skills group, where women learn about everything from opening a checking account to raising a child. In the afternoon, participants go to clinical or trauma groups to share their feelings and experiences. All the while, the counselors and clinicians at Hope House keep a close watch, keeping an eye on certain behaviors and making notes both for their benefit and for the participants’.

[mks_pullquote align=”left” width=”300″ size=”24″ bg_color=”#ffffff” txt_color=”#003359″]“You can’t go and write the participant’s treatment plan for them. They have to be a part of it. We always ask them, ‘What are your goals? What do you want to accomplish?’”[/mks_pullquote]

While meticulous in its structure, Hope House’s treatment process is anything but routine. Bentley, who joined Hope House as clinical director a little more than two years ago, has a hard-and-fast rule when it comes to addiction recovery.

There is no cookie cutter treatment.

“You have to look at the individual,” he says.

He and the counselors and clinicians under his supervision subscribe to the same person-centered care philosophy. Effective care cannot be given in an impersonal way. Everyone finds their own path into addiction, and as such, everyone needs their own path out. The approach is a unique one, but it’s already shown incredible results. Most of the women who enter Hope House not only come out clean; 85 percent leave gainfully employed.

Bentley attributes this success to the flexibility and deeply personal nature of Hope House’s treatment plans.

“You can’t go and write the participant’s treatment plan for them,” he says. “They have to be a part of it. We always ask them, ‘What are your goals? What do you want to accomplish?’”

For some, the answer is as simple as “I want to get clean.”

It takes a village to make that goal a reality, however, as Wilhelm can attest. When she first came to Hope House, she had nowhere to stay and no idea how to raise a toddler, let alone how to keep herself clothed and fed. With no relatives in Augusta, and no prospects for the future, she wasn’t afraid of what would happen to her in treatment so much as what would happen to her after she left. She’d lost hope. For herself. For the future. There was no path forward. No light at the end of the tunnel.

So, a counselor helped her find one.

“I would get mad and pack up my stuff, and I’d call my probation officer and tell him I was leaving,” Wilhelm says. “He would play my tape through, and he’s like, ‘If you leave, this is where you’re going to go.’ I had my three-year-old with me at the time, and I was dealing with not only my issues, but also guilt over what I’d put him through. He’d learned that anger was how we deal with our emotions.”

During one such moment of frustration, a counselor blind-sided her with a comment. “We know you want us to give up on you, but we’re not,” she said.

Another added, “I see something in you that you can’t see in yourself.”

During her stay, Hope House provided Wilhelm with all the necessary tools to lead a new and sober life. They’d given her a place to stay. They’d found transportation for her. They’d provided childcare services for Amari, and taught Wilhelm the life skills she needed to find and keep a full-time job and raise her son the way she wanted.

“That was a big relief,” she says. But the biggest relief was just knowing someone cared.

“We don’t subscribe to the old way of doing things,” Saltzman says. The traditional addiction recovery treatment model—the “break them down and build them up” mantra—doesn’t work, she says, because it misses the most important truth about addiction. “These women, when they come to us, they’re already broken.”

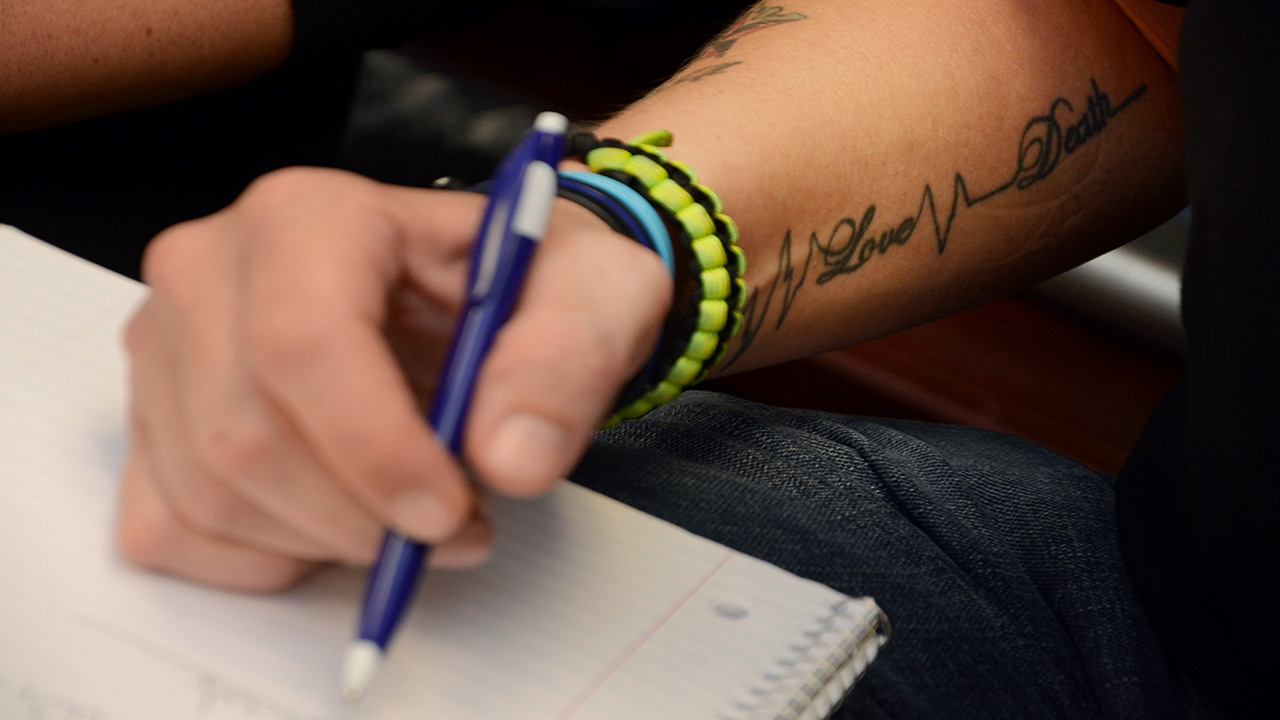

Many still bear the scars.

I Do This Every Day

”I tell the girls, ‘Don’t count the days; make the days count,” Wilhelm says. “It’s hard to get your life back in six months. I stayed 18 months altogether. At six months, I was just getting clear-headed.”

When she says, “the girls,” Wilhelm means the women at Hope House. Particpants, peers, friends. Women who are desperate to find the path to recovery. Wilhelm currently works at Hope House as a counselor assistant, sitting in on group sessions—the same group sessions she once participated in—to offer guidance and a listening ear. She’s also earning her GED. As soon as she gets it, she wants to enroll at Augusta University. Preferably in a program that will help her break into the mental health field.

Stories like Wilhelm’s aren’t unheard of, but they are exceedingly rare across the country. For many women living with opioid addiction, incarceration, and the rush to get high again afterward, can be a death sentence. More than one study places the risk of overdose death in the first two weeks after release at more than 100 times that of released inmates without substance use disorders. The problem is compounded by the relative lack of female inmates compared to their male counterparts. Fewer women arrested means fewer resources for helping women transition back into society.

Improving those odds and helping more women like Wilhelm is the aim of a new program developed by Johnson and Dr. Lufei Young. Johnson and Young, associate professor in the College of Nursing, recently received a $2 million grant from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration to develop a program to help male and female offenders overcome challenges with substance use disorders after incarceration. In addition to providing inmates with counseling services (by working with organizations like Hope House), the Augusta Area Comprehensive Offender Reentry Program will also provide FDA-approved medications to treat substance use disorders where appropriate. Those efforts, once underway, could prove crucial to saving lives in and around Augusta.

“What happens particularly with people with an opiate disorder is they withdraw from those substances while in prison,” Johnson says. “During incarceration their tolerance is lowered. Once they return to their community… they try to return to the same level they were using at prior to incarceration. They end up overdosing and potentially dying.”

Johnson and Young hope to help 400 individuals over the course of five years—30 women and 50 men annually. Funding for the program began at the end of September 2018. Johnson said he’s eager for the program to get up and running.

“Honestly,” he says, “God leads you in certain directions.” His direction, at least for the foreseeable future, will be to help put together a network of care providers throughout the state to tackle addiction—in all its many forms—as efficiently as possible.

Saltzman, reflecting on the partnership between the university and Hope House, subscribes to a similar philosophy. “It’s surreal, sitting here,” she says. “But it’s like Dr. Johnson said. We’re where we’re supposed to be.”

Saltzman says she’s excited for the program and for the good it will do in the Augusta community. Getting to work with the Ambers of the world (and getting to love the Amaris) has shown her firsthand the importance of helping more women. More mothers. In that way, the value of a partnership between Hope House and Augusta University is immeasurable.

[mks_pullquote align=”right” width=”300″ size=”24″ bg_color=”#ffffff” txt_color=”#003359″]“As long as they’re alive, there’s hope.”[/mks_pullquote]

She still thinks back to her first year at Hope House and that first experience with a mother choosing addiction over her child. It’s something she hopes never to repeat. Something she’s needed her own healing journey to cope with.

The memory becomes even more poignant when she glances across the conference room table. Not so long ago, she met another young mother on the brink—a young woman with little left to lose and no hope of her own. Someone stumbling in the dark, searching for the light. Leaning over, she rests a hand on Wilhelm’s shoulder.

“As long as they’re alive,” she says, “there’s hope.”

Wilhelm smiles. She’s thinking of a woman, a peer in the program. An expectant mother. She asked if Wilhelm could be in the room with her when she gives birth. Asked if she could be there as a guide. As a friend.

“Sometimes I wake up in the morning, and I’m like, ‘This is my job,’” Wilhelm says, looking to Saltzman, tired eyes brimming with excitement and the remnants of tears. From outside, the warm summer sunlight filters into the conference room through half-opened blinds, touching a face that seems now to glow with a light all its own.

“I do this every day,” she says. “I do this every day.”

Augusta University

Augusta University