Colorectal cancer is the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States, affecting both men (1 in 23) and women (1 in 26) fairly equally, according to the American Cancer Society.

The American Cancer Society estimates that 52,550 people will die from colon cancer in 2023; however, the death rate from colorectal cancer has been dropping in both men and women for several decades. One of the big reasons for this decline is the increase in regular screenings for all cancers during yearly checkups, allowing for early detection, which can lead to better treatment options, as well as improved treatments for colorectal cancer in recent years.

But there is another reason why the numbers have been trending in the right direction: high-fiber diets and the growing popularity of high-fiber foods like avocados, berries, figs and artichokes, just to name a few.

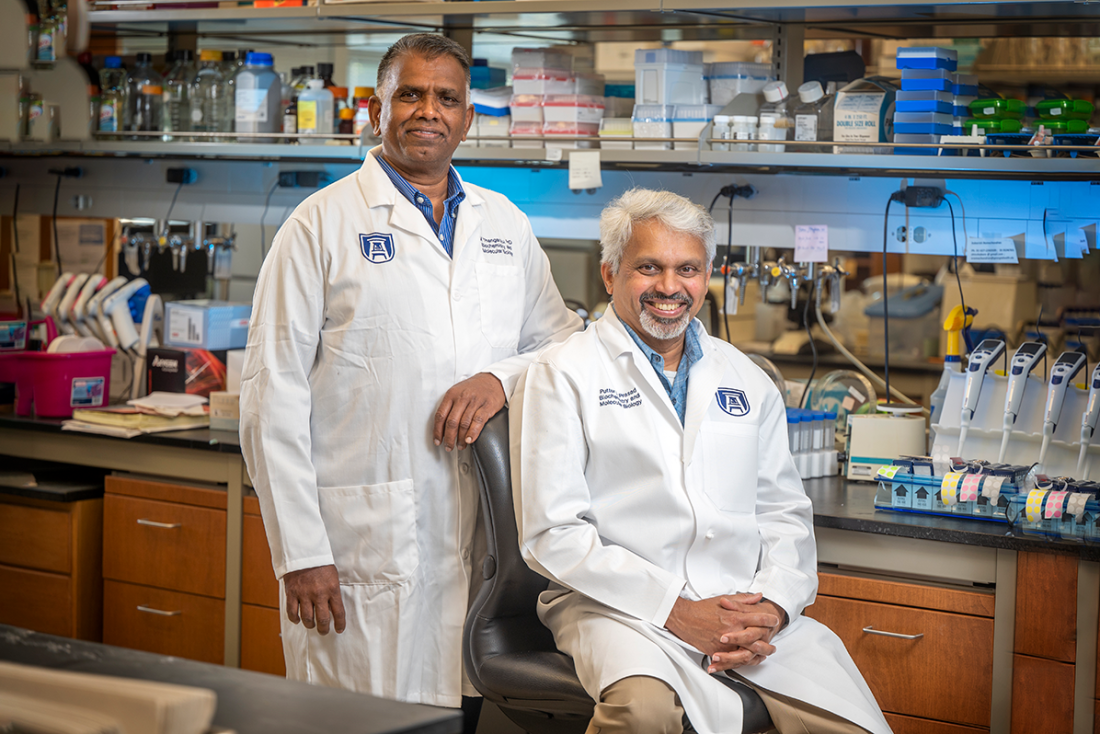

Muthusamy Thangaraju, PhD, an associate professor at the Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, was recently awarded an RO1 grant for $2,106,745 over five years from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for his project titled “GPR109A is a G-protein-Coupled Receptor for the Bacterial Fermentation Product Butyrate and Functions as a Tumor Suppressor in Colon.”

Thangaraju’s research team from the Medical College of Georgia includes co-investigators Puttur D. Prasad, PhD, professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at MCG, Nikhil Patel, MD, associate professor in the Department of Pathology, and Santhakumar Manicassamy, PhD, professor in the Department of Medicine.

He has also received the Pilot and Feasibility Grant Award from the Polycystic Kidney Disease Research Resource Consortium for $127,000 over two years for his project titled “Netrin-1 is a New and Novel Biomarker and a Potential Therapeutic Target for the ADPKD Cystogenesis,” and he is also a co-investigator on another study that received an RO1 NIH grant through Georgia Tech.

Vinata B. Lokeshwar, PhD, chair and professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, and Bal Lokeshwar, PhD, the J. Harold Harrison, MD Distinguished University Chair in Basic Sciences, are collaborators with Thangaraju on the project that received the grant from the Polycystic Kidney Disease Research Resource Consortium.

“I am very excited about the grants we have received for our research on suppressing colorectal cancer. We are at a very pivotal time in both our research and the battle against all forms of cancer, as every day new discoveries are altering how we approach treatment and prevention,” Thangaraju said.

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, most Americans do not meet their recommended daily allowance (RDA) for fiber. On a high-fiber diet, fiber consumption should meet or exceed the RDA for fiber — for adult women, 22 to 28 grams of fiber per day; for men, 28 to 34 grams per day.

This plays a part in helping prevent colon cancer because it has long been known that a high-fiber diet protects humans against some cancers, especially colon cancer.

Despite this knowledge, the molecular mechanisms behind the high-fiber diet and associated colon cancer prevention have not been well understood.

In his research, Thangaraju has found that GPR109A, a G-protein-coupled receptor for the bacterial fermentation product butyrate (BTR), the ketone body b-hydroxybutyrate (BHB) and the vitamin niacin (NA) provide a formidable barrier against colon cancer through the metabolites that are generated during digestion in a high-fiber diet. Short-chain fatty acids, especially butyrate, which are generated in the colon by bacterial fermentation of dietary fiber, are what have been identified as the protection against colon cancer through the activation of GPR109A.

Taking it a step further, chemical carcinogens and xenobiotics in the diet play a significant role in colon cancer formation and p53 mutation (p53D) or inactivation is observed in about 60% of colon cancer. Similarly, a high frequency (40-60%) of KRAS mutation (KRASD) is observed in organisms that are exposed to environmental chemical contaminants, and about 40-45% of colon cancer is associated with KRAS mutation.

“The intestinal tract, including the colon, is often the first site that is exposed to these carcinogens and xenobiotics,” Thangaraju said. “Oncomine database analyses show a positive correlation between GPR109A and p53 and a reciprocal association between GPR109A and KRAS mutant colon cancer. These observations provide evidence that GPR109A may be a central player in p53 activation. The chemical substance that activates GPR109A is niacin, the precursor of NAD+, and p53 is an NAD+-dependent molecule. Niacin deficiency impairs p53 function.”

According to Thangaraju’s research, niacin-induced GPR109A activation can enhance p53 function by decreasing cAMP, which enhances the binding of MDM2 to p53 and the resulting proteasomal degradation, inhibiting SIRT1, a p53 deacetylase, and attenuating p53 deacetylation independent of SIRT1. Similarly, b-hydroxybutyrate, the physiologic agonist of GPR109A and the primary ketone body in mammals, potentiates p53 function by increasing p53 acetylation and also induces apoptosis in p53 mutant colon cancer (p53D CC) by promoting the degradation of mutant p53 (p53D) via inhibition of HSP90 chaperone, as well as the transcription of mutant p53 (p53D) through HDAC inhibition.

“Further, the rate-limiting enzyme in ketogenesis, HMGCS2, is induced by bacterial metabolites in the colon and bacteria-derived Butyrate is a precursor for ketogenesis. HMGCS2 expression is silenced in colon cancer. We found that GPR109A deficiency limits HMGCS2 and its downstream targets HMGCL and BDH1 expression,” Thangaraju said.

“With this grant, we will study the link between commensal bacterial metabolites and the GPR109A-ketogenesis-p53 axis by expounding on the pathways that are involved and determining the impact of colon-specific deletion of Hmgcs2 on chemical carcinogen and xenobiotics induced colon cancer.”

Augusta University

Augusta University