In the realm of cancer prevention, few tools are as powerful as the colonoscopy. This procedure, which allows doctors to examine the inner lining of the large intestine, plays a crucial role in detecting and preventing colorectal cancer. In addition to the colonoscopy, other screening options are also available, including the sigmoidoscopy and the fecal immunochemical test (FIT).

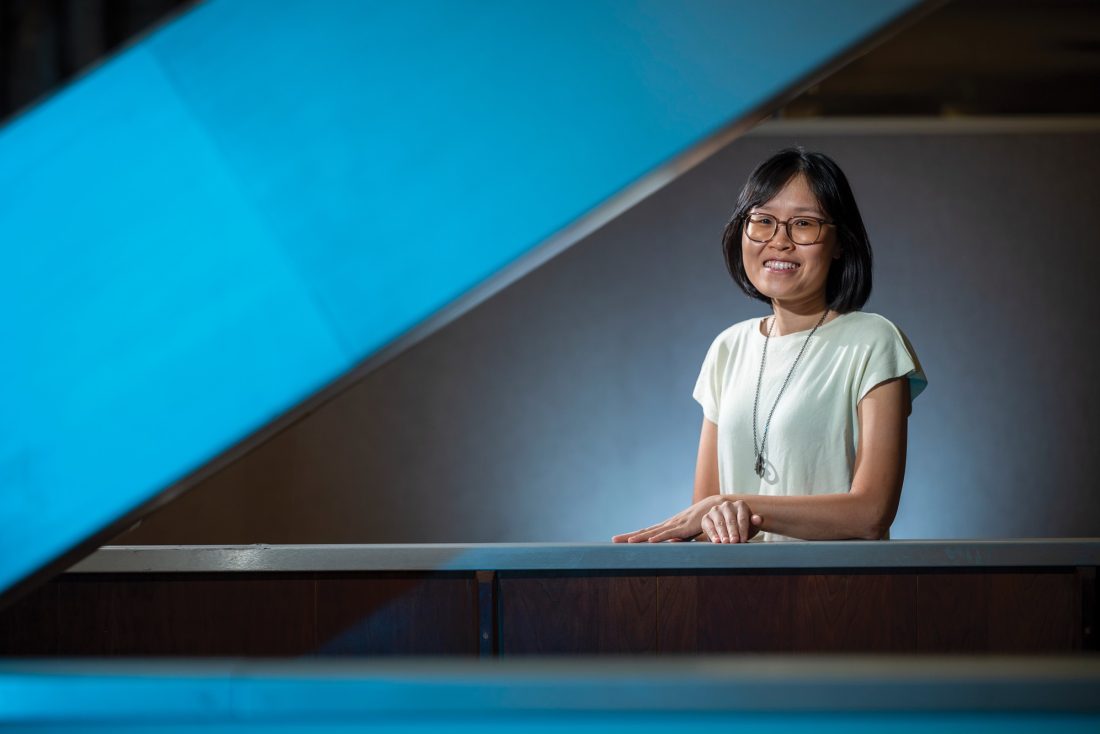

Despite the proven benefits, access to colorectal cancer (CRC) screenings is still uneven, particularly in certain areas of Georgia. Meng-Han (Mina) Tsai, PhD, an assistant professor in the Department of Medicine in the Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University and a researcher with the Georgia Cancer Center, is dedicated to addressing this disparity through her research.

“My research is driven by the need to improve health care access among minority and underserved populations,” she said. “In Georgia, there are significant disparities in the availability of colonoscopy services, which can have a profound impact on colorectal cancer outcomes. By focusing on these disparities, I hope to show the barriers that prevent people from accessing these essential services and develop strategies to overcome them.”

In her recent publication, Intersection of Poverty and Rurality for Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer Survival, published in JAMA Network Open this month, Tsai, along with Steven Coughlin, PhD, and Jorge Cortes, MD, combed through data from 22 cancer registries in 22 different cancer centers, including the Georgia Cancer Center at Augusta University. Their findings show that if a colorectal cancer patient is between the ages of 30 and 39 and they live in a rural community where poverty is rampant, the patient is 50% more likely to die from colorectal cancer compared to patients in the same age range living in an urban community where medical services, including colonoscopies, are readily available.

“Early onset colorectal cancer (EO-CRC) has increased recently,” Tsai said. “However, patients living in rural and poverty areas generally lack access to appropriate care. We examined the connections between rurality and poverty on EO-CRC survival and considered different age groups beginning at age 20 all the way to age 49. What I found surprising is for young adults living in rural areas with persistent poverty, ages 30-39 years showed higher estimates on cause-specific mortality for CRC with 50% increased risk.”

According to the American Cancer Society, colorectal cancer is the third-leading cause of cancer-related deaths in men and the fourth-leading cause in women, but it is the second most common cause of cancer deaths when numbers for men and women are combined. Estimates from the Cancer Society show there will be nearly 150,000 new cases of colorectal cancer in 2024. The good news is that with improvements in colonoscopy technology, including the use of artificial intelligence, the number of new colorectal cancer cases continues to decline.

“Our goal is to create a health care system where preventive services are accessible to all,” Tsai said. “By increasing screening rates, we can detect colorectal cancer at an earlier, more treatable stage and ultimately save lives. I hope that my research will lead to policy changes and resource allocation that prioritize cancer prevention in underserved areas. Every person deserves the chance to live a healthy life, and, through research and advocacy, we can make that a reality.”

Several factors contribute to the lack of access to CRC screening in certain parts of Georgia, including socioeconomic barriers, such as lack of insurance or transportation, as well as a shortage of health care providers in rural areas.

Tsai’s research also points to cultural and informational barriers that can prevent people from seeking out screening. To address these issues, Tsai advocates for community-based interventions that involve local stakeholders in promoting equitable access to colorectal cancer screening and more awareness of CRC risk and potential symptoms for young populations.

“Community engagement is key,” she said. “By working with local organizations and health care providers, we can develop strategies that are tailored to the specific needs of each community.”

Augusta University

Augusta University