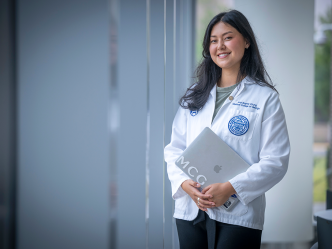

As a child, Bria Carrithers would watch her mother, a physician assistant — and Medical College of Georgia graduate — put on her white coat and go to work, and Carrithers would dream of pursuing a new career in medicine.

“Ever since then, I’ve found myself really committed to the field,” she said. “I never wanted to be anything else besides a physician.”

And so, when she entered Spelman College, she had no doubt what she wanted to study, majoring in Biology and Pre-Med.

“I’ve always been driven in whatever it was that I put my mind to,” she said.

Despite her determination to make it in the field of medicine, she has had her moments of self-doubt like anyone would.

After a long struggle to find the right place to study, including some disheartening rejections, Carrithers chose her mother’s alma mater, the Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University.

“That was reassurance that, okay, you might be knocked down, but you can still get up and still keep fighting, so that’s what I ended up doing,” she said.

Now, as she prepares for her next two years of medical school, she’s hoping to capitalize on the faith MCG has placed in her by paying it forward to a community she knows all too well: her hometown of Albany.

A dearth of doctors in rural communities

Though Albany is not strictly a rural town, it’s far from a large metropolitan area, and Carrithers’ choice to return home to a smaller city is becoming rarer in the state of Georgia. A large majority of medical students are choosing to do rotations and practice in the Atlanta area and other larger cities in the state.

In some small towns, there is only one doctor practicing a certain discipline. In others, people have to travel many miles to even find a doctor, an additional burden given the fact that a number of them are impoverished or without insurance. There are currently nine counties in Georgia without a physician. Sixty-four counties are without a pediatrician and 79 are without an OB-GYN. All in all, Georgia is worse than the national average for areas without doctors and ranks near the bottom in physicians per capita.

The Georgia Board for Physician Workforce has attempted to correct this shortage with the Physicians for Rural Areas Assistance Program, which offers a loan of up to $25,000 to doctors who practice in rural areas.

Another organization is completely devoted to growing the number of rural doctors: the Georgia Rural Health Association, which has been in existence for 38 years. Its mission includes promoting rural health as a distinct concern in Georgia and encouraging the development of appropriate health care resources for rural Georgia residents.

In recent years, the Medical College of Georgia has gotten more involved in these efforts. The college has proposed an innovative program that would pay the full tuition for doctors who agree to serve in rural communities in the state for at least six years. The hope is that this proposal will pass in the Georgia legislature by the end of the 2020 session.

MCG Dean David Hess recently told the Augusta Chronicle that putting a primary care physician into a rural area will save $3 million statewide in insurance and patient costs, partially because fewer patients will go to the emergency room for basic .

Back in February, MCG also held the Rural Emergency Practice Conference, and currently offers the Rural Family Medicine Residency Program, which accepts two residents each year in either Waycross or Blackshear, Georgia.

In addition, the university is home to the Center for Rural Health Support and Study, which takes a multidisciplinary approach in order to assist the stabilization of rural hospitals.

The college’s Southwest Campus offers the Certificate of Rural Community Health, which targets students from rural communities who wish to return to an area like their hometown to practice.

All of this is part of Augusta University President Dr. Brooks Keel’s goal to prioritize rural health.

“Residents of rural communities often lack sufficient access to health care services and specialized treatments, with no other option than to travel long distances to Augusta or forego treatment completely,” Keel said last year.

The ultimate goal of these initiatives is to ease those health care burdens by making it easier for medical professionals like Carrithers to choose to serve rural communities that need them.

The importance of regional hospitals

For Carrithers, returning home is a very personal decision.

“Albany really made me who I am,” she said. “I’ve gone to Los Angeles, I’ve gone to New York, but I always want to go home.”

That desire makes it easy for her to see herself working at least five years in Albany.

“I know the special place that it is,” she said. “It helped to make me special, so I want to leave a lasting mark there.”

Because Carrithers is particularly interested in helping those suffering from sickle cell anemia and cancer, she wants to go into the field of hematology/oncology.

She calls those suffering with sickle cell “the forgotten people,” in part because she’s seen the struggle firsthand.

A friend of hers was stricken with the disease when she was in high school.

“Seeing my friend struggle sparked an interest in me to learn more about the disease,” she said.

Being at MCG certainly puts her in a place where she can accomplish that. AU Health has an internationally recognized Sickle Cell Center, which not only treats patients but conducts research on fighting the disease.

Though she will be on Albany’s Southwest Campus, she also expects to spend time in rural Georgia towns like Bainbridge and Americus.

“I definitely see the importance of regional hospitals,” she said. “When communities lose regional hospitals, communities die.”

And she wants to do her part to keep her hometown from dying.

“We have so many people [in Albany] living below the poverty line, and how would that affect things 20 years down the road if we’re not able to put in preventative practices now?” she asked.

Dr. Louise Thai, who teaches infectious diseases and microbiology to second year students like Carrithers certainly agrees that she can make a difference.

“With all of her potential, I can see her getting very far,” she said. “I told her the sky is the limit, go for it.”

Augusta University

Augusta University