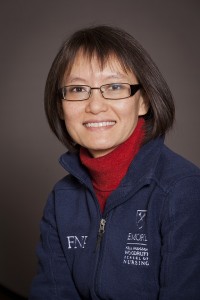

The following is the third segment of an ongoing series about Quyen Phan, a student in the Augusta University Doctor of Nursing Practice Program and a clinical instructor at Emory University. Fearing arrest, Phan fled Vietnam with her family in 1988. This is her story. (Read Part 2 here)

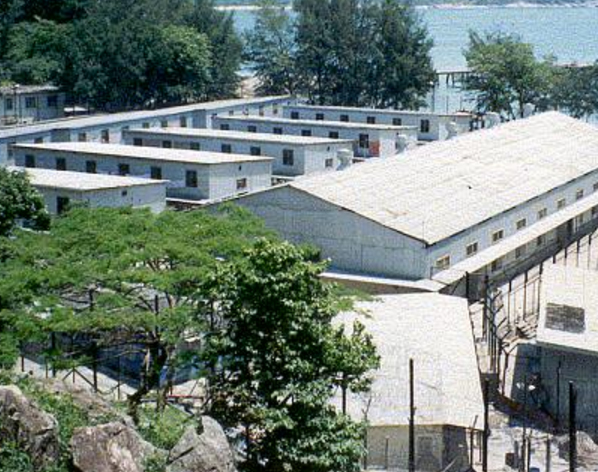

Time seemed to pass more slowly in Chi Ma Wan.

Equal parts prison and refugee camp, the facility, managed by Hong Kong’s Correctional Services Department, was hardly the warm welcome Vietnamese refugees might have expected from the outside world.

Inside, many families were confined to quarters unfit for an individual, forced to sleep on triple bunks to conserve space. Food came regularly, but in scarce portions. Entertainment was at a premium. Life as a refugee proved a disheartening experience, even for those who had left their homeland in fear.

But the experience was made all the worse by one painful realization.

Phan and her father had fled Vietnam by boat on the night of June 12, 1988. After two separate encounters with pirates, the pair spent more than a week at sea.

In June of 1988, the inflow of Vietnamese refugees into Indochinese countries skyrocketed. Several countries developed plans to limit and eventually stop the influx. Five countries, who would later come together as members of The Steering Committee of the International Conference on Indochinese Refugees, each set separate dates to enact a “cutoff” of sorts. After said cutoff, “Boat People” arriving on the shores of any of the participating countries would no longer be deemed “prima facie” (“on the face”) refugees and would instead be considered illegal immigrants until their status as legal refugees was confirmed by both the host country’s Immigration Bureau and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

Those deemed illegal immigrants would be returned to their country of origin.

Thailand, Malaysia and the Philippines established their cutoff date as March 14, 1989. Indonesia settled for March 17, 1989.

Hong Kong, the country Phan and her father fought so desperately to reach, enacted its Comprehensive Plan of Action (CPA) program on June 16, 1988.

Phan and her father had missed their best chance at freedom by a single working week.

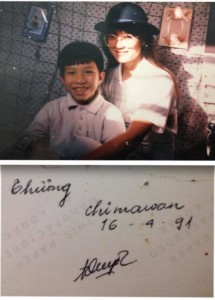

“We were the 406th and 407th people to arrive in Hong Kong after the cutoff date,” Phan said. “It took the United Nations almost two years to get to us.”

Their spirits fell, but only briefly.

Three months after her arrival in Chi Ma Wan, Phan received some uplifting news.

Her mother and brother were alive.

“We found out that two weeks after we left, my mother and brother found a way to escape Vietnam,” Phan said. “We didn’t hear back from them until three months later, in Chi Ma Wan.”

The reunion would prove a short-lived one, however.

Shortly after arriving in Chi Ma Wan, the Hong Kong Immigration Bureau deemed the Phan’s family illegal immigrants. The state’s reasoning?

“They said we didn’t face any persecution in Vietnam,” Phan said.

The family appealed, and for a second time, the Hong Kong Immigration Bureau deemed Phan’s family illegal immigrants.

During the months-long appeal process, Phan celebrated her 18th birthday. Now an emancipated adult in the eyes of the Hong Kong Immigration Bureau, her case was considered separately from her family’s, momentarily saving her from being sent home. Even though her life still hung in the balance, though, her family’s fate had already been decided.

“My dad, mom and my brother were separated from me at that point,” Phan said. “They were moved to a transition camp to be returned to Vietnam.”

For Phan’s family, especially her father, who had fled Vietnam for fear of political imprisonment, the idea of being moved to a transition camp was synonymous with death. The family took the news hard, Phan included.

One of the only things that kept her going was the chance to educate herself.

“When I was in the camp, I didn’t speak any English,” she said.

An embargo with the United States had, to that point, shielded her from American culture. In fact, she knew almost nothing about Hong Kong, despite having spent months within the country’s borders. The one country she did know was Thailand, and even that was a fleeting dream. She said that was the basis of her hope for life outside the camp.

“I knew there had to be something different because of my dad’s experiences,” she said. “The only kind of expectations, the only kind of hope I had at that point was what I knew about his time in Thailand.”

Determined to continue her education, Phan set her sights on learning one thing above all others: speaking English.

“We didn’t have teachers in Chi Ma Wan, so it was just me and a group of friends,” Phan said. “We would get grammar books and Vietnamese-English and English-Vietnamese dictionaries, and we would just talk away in broken English. Whatever we didn’t know, we would look up and learn to plug it into our sentences.”

Before their family was separated, Phan said she even taught some English to her family, an experience she said has stayed with her to this day.

“Once when my dad made me teach him English, I told him I would never teach in my life,” said Phan, now an instructor at Emory University. “I thought for sure it would never happen.”

As her English progressed, though, Phan said snippets of the outside world began to flood into Chi Ma Wan.

“We learned some while in the camp,” she said. “We learned a little about what life outside would be like.”

One thing she learned from the nongovernmental organization (NGO) representatives who occasionally came to visit was that traveling from one country to another wasn’t always illegal.

“They told us you could go from one country to the next without getting permission from the local police,” she said. “I said, ‘How do you know if people move from one city to another? From one country to another?’”

An NGO representative responded casually, “So what? It’s their life.”

Phan said the realization took her completely by surprise.

“You couldn’t go from one place to another without telling the police in Vietnam,” she said. “That’s something I grew up with. I expected it everywhere.”

It was a harsh lesson to learn, especially knowing that her parents awaited their death in a transition camp. Phan’s thoughts lingered on family and the life they would never get to live if they were shipped back home. But fate, it turned out, hadn’t abandoned Phan’s family

In their darkest hour, with the date of their return to Vietnam drawing near, the United Nations deemed the family legal refugees.

“Our final round of appeals got through,” Phan said. “My mom and dad and brother were plucked from that transition camp and moved elsewhere to await resettlement. After some time, they were transferred to another camp in the Philippines, where they waited for 14 months for someone to sponsor them.”

It was the best news they’d heard since leaving Vietnam.

But after five years in Chi Ma Wan, several of them spent separated from her family, Phan received some good news of her own. News she said she never expected to hear.

A close family friend in another country had chosen to sponsor her. For the first time in two decades, she would be setting foot into the “real world.”

It was an exciting, terrifying revelation.

Phan, a 23 year old with a shaky grasp of English and no understanding of the outside world, learned that not only would she be leaving Hong Kong …

… she was going to Canada.

Augusta University

Augusta University