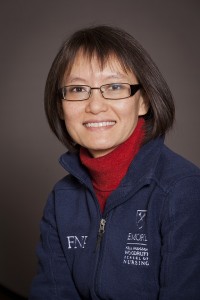

The following is the first segment of an ongoing series about Quyen Phan, a student in the Augusta University Doctor of Nursing Practice program and a clinical instructor at Emory University. Fearing arrest, Phan fled Vietnam with her family in 1988. This is her story.

Flight from Vietnam:

It was a dry and dreary summer when Quyen Phan left her family’s home forever.

Dry, of course, is a relative term in Vietnam. It’s always raining somewhere in the little seaside state – a side effect of the country’s stretching into three separate weather zones and, as a result, three separate rain seasons. Combined with the region’s blistering heat and tropical humidity, the moist summer air quickly becomes uncomfortable.

In June of 1988, though, the air was a lot like the country’s dubious “reunification” effort.

Suffocating.

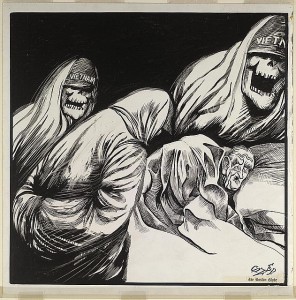

Thirteen years earlier, the bloodiest conflict of the Cold War had come to a close when North Vietnamese and Viet Cong troops, having invaded and captured Saigon, stormed the South Vietnamese presidential palace. Today, the unified Vietnamese government officially celebrates April 30 as Reunification Day, but Vietnamese living abroad have another name for it.

They call it “ngày mất nước,” meaning “the day we lost our country.”

Phan, who was a child at the time, has only vague memories the Vietnam that came before. Now a student in the Doctor of Nursing Practice program, she said she remembered her former home as a bleak and draining portrait of post-Cold War Communism.

“I don’t know for sure what it’s like in North Korea right now, but from what I’ve heard, Vietnam was kind of similar to that,” she said. “Depressing, oppressive, very poor and very dangerous.”

Billed today as an exotic tourist destination, the country’s economy, now reportedly thriving, was then impossibly grim. Before fleeing the country, Phan said her mother had to quit her job as a pharmacist to find more lucrative work.

“She had to quit her job at the pharmacy to become a ‘businessperson’ so that she could support us,” Phan recalled. “And I mean ‘businessperson’ in a very loose sense of the word.”

According to Phan, her mother would buy and sell local goods, working as a sort of storefront middle man to help put food on her family’s table. It was a powerful sacrifice, but only a mildly successful one. She said most “middle class” Vietnamese families suffered similar fates.

“It was very depressing,” Phan recalls.

But while Phan’s mother was busy trading market goods, Phan’s father was trading something far more dangerous: opinions.

Like most Vietnamese workers in the late ‘80s, Phan’s father was severely overworked and woefully underpaid. A staffer for a local transportation union, he soon took to protesting, writing a letter to his place of employment to express his concerns.

Phan said her father’s discontent was a side effect of his having been born in Laos. Having grown up in Laos, and later, Thailand, he had seen the world that lay beyond the Communist red and gold, and he was none too pleased with the vision of Vietnam he’d returned to.

Vietnam, it so happened, wasn’t very pleased with him either.

“Throughout my dad’s life, it was very hard for him to do anything,” Phan recalled. “My father was officially a war refugee. Since he returned to Vietnam in 1961, he’d been labeled a capitalist sympathizer.”

Phan’s father was quickly reprimanded and labeled a dissident, a title which, combined with his foreign birth and presumed “capitalist sympathies,” served as death warrant in the newly established republic.

It was a recipe for disaster, but the flavor was an all too familiar one at the time.

Unfortunately, Phan’s father was never one to stand down. His dissidence quickly turned into a discrete rebellion.

“Together with four or five of his other friends, other expatriates, he started meeting regularly to circulate documents about what workers should be paid and how they should be treated,” Phan said. “These were all people who had a glimpse of life outside of Communist control. These were all people who cared.”

Or so her father believed.

As the family would later learn, one of the individuals involved with the meetings was actually a government informant.

Having learned of the infiltration, the workers’ group dissolved seemingly overnight. News of their impending arrest became public knowledge soon after.

“It was then my dad decided it was no longer safe for us to live in the country,” Phan recalled.

The scene is reminiscent of something from George Orwell’s “1984:” Disgruntled workers battling the system, betrayed by one of their own for “retaliating” in the mildest of ways. Unfortunately, the practice was frighteningly common in post-war Vietnam.

“The communist government had organized these sorts of small neighborhood units,” Phan said. “And the unit leader, he acted as a sort of spy for the government. Every single little thing we did, they observed and reported it back to the police.”

She said that knowledge, that feeling of constantly being watched, bred a culture of perpetual fear in her homeland.

“You’d think of teenagers as being carefree, worrying only about their friends or their lifestyle,” Phan said. “At 16, I was acutely aware that whatever I said or did could come back and haunt not only me but also my family. You couldn’t trust your family or your friends or your neighbors. Anyone could be an informer.”

For Phan’s family, that constant fear was too much to bear.

Shortly after being discovered, Phan’s father made the toughest decision of his life.

He knew that if he wanted to survive, he would have to leave Vietnam. He also knew that if he left, he couldn’t leave his wife or children behind. Families were the perfect target for vengeful authorities. In his absence, his children or his relatives would do just as well as prisoners. If he left, his family would have to go with him. There was no way around it.

But smuggling a family of four out of an openly hostile country isn’t an easy task. Or an affordable one.

After weighing his options and consulting with his wife, Phan’s father made up his mind. He would hire the captain of a small, three-person boat to ferry himself and another family member out of the country. Then, once they were free, he would send for the others.

“We decided that it was safer for me and my dad to leave first,” Phan said.

The decision didn’t come easily. Phan said she recalled pleading with her father to stay, arguing that if their family were to escape, they would do it together. Ultimately, it was her mother’s intervention that changed her mind.

“She sat me down and had a long talk with me,” Phan said. “She explained the situation to me and said that she and my brother would be right behind us. After that talk, I never doubted that we would be reunited.”

That reunion came sooner than anyone expected…

Be sure to check Jagwire next week for part two of “From refugee to DNP,” an ongoing series about Quyen Phan, one of Augusta University’s most fascinating students.

Augusta University

Augusta University