Second-year Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University student Alaina Godbee has a close relationship with her grandmother, Jeannie Donaldson, or Nani as she calls her.

Every time she goes home to Statesboro, Georgia, her Nani asks her about medical school. Earlier this year, they talked about the anatomy course she was beginning, and Godbee began to explain about the First Patient Discovery Project that works with the Anatomical Donations program at MCG, which is part of the Department of Cellular Biology and Anatomy.

After the conversation and hearing about what the program entails, Godbee’s Nani thought it sounded like a good idea and said she wanted to do it, too. The decision didn’t surprise Godbee.

“With her personality, I was not surprised,” she said. “The program is a great thing to do, and I really respect everybody that has donated their body for this. I think that it’s great that she wants to do it.”

About the program

The donation program is housed in MCG, which has been teaching anatomy since its inception almost 200 years ago.

It is regulated by the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act, which has been adopted by all 50 states. It states any individual of sound mind and at least 18 years of age may give their body to medical science. There is no maximum age limit for those who wish to donate, and the gift takes effect at the time of death.

“Being aware of how things are in the body, how they’re situated, the 3D and spatial awareness; there’s just nothing that compares to learning on your donors. Also, our students don’t just look at this as, ‘I’m learning anatomy.’ They also look at these donors as, ‘this is my first patient that I have to care for.’”

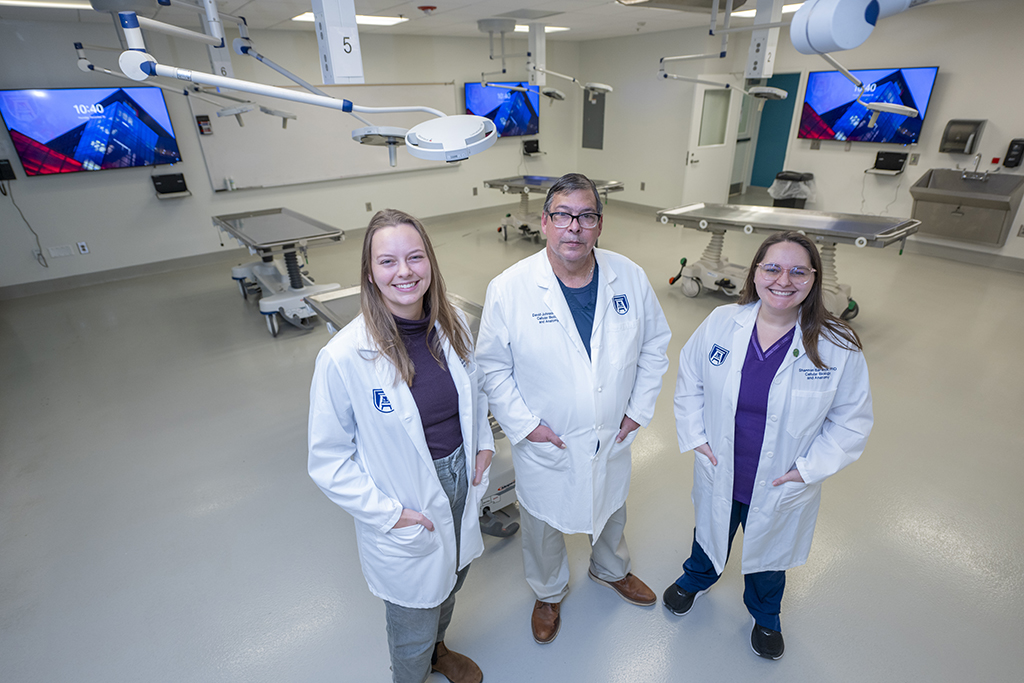

Morganne Manuel, PhD, director of the gross anatomy component at MCG

The length of study depends on what type of study the body is used for and cannot be determined in advance, but can range from three months up to three years. AU does not pay for body donations; this policy is standard throughout the United States under the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act. However, cremation services are provided by the program at the conclusion of studies at no cost to the donors’ families.

AU receives between 70 to 80 body donations every year. The program then provides support for educational activities and interdisciplinary research through the colleges of medicine, dentistry, allied health and graduate studies.

Morganne Manuel, PhD, is the director of the gross anatomy component at MCG. She has been teaching anatomy for 10 years, including the past five at AU. During that time, she has seen educators and researchers alike pull back from digital “virtual anatomy tool” systems and gravitate toward donors after experiencing the limits for available digital systems when it comes to learning anatomy. The students work together as a team because oftentimes, “medicine is thought of as you’re working by yourself, and it’s never that.”

“Being aware of how things are in the body, how they’re situated, the 3D and spatial awareness; there’s just nothing that compares to learning on your donors,” Manuel said. “Also, our students don’t just look at this as, ‘I’m learning anatomy.’ They also look at these donors as, ‘this is my first patient who I have to care for.’

“My task is to teach the students anatomy, to prepare them for when they will see their patients in the hospital and to understand the foundational knowledge of anatomy,” she continued. “My primary role is teaching them that foundational knowledge through our donors that they can apply to their future patients.”

Students thrive from experience

Godbee is still deciding what field she wants to pursue, but has always known that she wanted to work in health care. Once she started taking her prerequisites, especially biology and biochemistry, that solidified her career path.

During her second semester, her class began working in the lab with the body donation program with some focus on the musculoskeletal skin module. The students are separated into groups of four or five and share one donor.

They spoke with a chaplain beforehand and then learned how to prepare for labs. Faculty made illustrations on each step of the lab and explained how the process would work. Then on the first day, they entered the lab and were introduced to their donor. She found the anticipation was worse than the initial experience of seeing a donated body.

“It’s definitely something that feels different at first, but with anything that you do consistently, the initial shock fades,” Godbee said. “That allowed me to focus more on learning and the responsibility that comes with working with someone who chose to donate their body for our education. Even as the lab became more familiar, there were still moments that reminded me of the humanity of our donor and the privilege of being trusted with their gift. Those moments reinforced the seriousness of what we were learning and helped ground the anatomy lab in respect rather than routine.”

Third-year medical student Morgan Kuchar recently chose obstetrics and gynecology as her specialty. She has always loved science and considered being a medical examiner, but as she got older, her grandfather developed Alzheimer’s. She said watching him go through the disease progression and interacting with his neurologist, Kuchar found herself more drawn to interacting with patients and families.

She joined MCG in 2023 and had prior experience as an EMT. She said the program was crucial for her education because she learned about pelvic anatomy. She expressed gratitude to the donors and their families, saying the emotional and educational impact of the program is something that cannot be replicated elsewhere.

“Pelvic anatomy is difficult to study from a textbook. It’s very three-dimensional,” Kuchar said. “I don’t think there’s any better way to learn than by dissecting a donor. The educational aspect is incredibly important but learning how to be uncomfortable and recognizing the gravity of the sacrifice donors have made is just as meaningful. Balancing gratitude and responsibility while trying to get the most out of the experience was an important part of the learning process.”

After the completion of studies, there are two body donor memorial ceremonies, one for the students and one for the families. A non-denominational memorial service is held on campus to honor the individuals whose bodies were donated. The service is coordinated by licensed funeral home directors and conducted by AU’s chaplains, faculty and students. The event is often attended by the donor’s family and friends. Families can choose to have their loved one’s ashes returned to them for private burial or buried in the Memorial Garden on Augusta University’s Health Sciences Campus.

“The letter isn’t for the families to read, but it’s a way to say our own ‘thank yous’ and talk about our experience. That was really powerful. I think it also reminded me of how much of a bonding experience it was for everyone. It’s also something that binds us to physicians that came before us.”

Third-year MCG student Morgan Kuchar

Both Kuchar and Godbee said at the student ceremony, flowers and paper were handed out and the students wrote a letter to their donor, expressing anything they wanted to say.

“The letter isn’t for the families to read, but it’s a way to say our own ‘thank yous’ and talk about our experience. That was really powerful,” Kuchar said. “I think it also reminded me of how much of a bonding experience it was for everyone. It’s also something that binds us to physicians that came before us.”

Although donor identities remain confidential, Godbee said students are allowed to give their donors a name of their choice, as a way of humanizing them. She said in her letter she wrote down things that happened during their time together as well as things she was thankful for.

“I think we all did a really good job of respecting our body donor, from how we talked about them or how we did our dissections to how we treated the lab and how we cleaned up,” Godbee said.

A family’s impact

Rachelle Grant’s parents, Ralph and Nancy Gammon, were living in the Augusta area when they first learned about the donation program. AU representatives for the anatomical donations program visited their church and discussed the background and provided information. To Grant’s recollection, most of the church signed up, including her parents.

At first, she was opposed to the thought of someone studying her parents’ bodies after their death while not having a full understanding of what was going to be done.

“I was pregnant at the time and I was asking, ‘Why are you doing this?’” Grant said. “The group from AU explained what a wonderful thing it is and how it helps the students, doctors, therapists, everyone learns about the anatomy and the biology of the body and maybe they could figure out some answers. It made sense.”

Grant’s father passed away of a heart attack in October 2002 while he was cutting the grass for a neighbor, “earning some extra golfing money.” Her mother died in February 2023.

Her father’s body was with the program for approximately three years before he was included in the memorial service in 2005. Grant’s mother was part of the November 2025 ceremony after almost two years.

Grant said hearing back from the program once their study was complete was difficult because as a family, they had already grieved once. She takes solace in knowing her parents contributed to students’ education.

“It was very important to both of them; they loved science and they loved learning all about the body and knowing that that would help with the further education of all of those students, or whoever worked on them to learn something new, to see the inside of the bodies and how it really works, and not look at dummies or models or videos,” Grant said. “These students had their hands on, inside and working with them. The visual is hard, but knowing that it was for a phenomenal reason, they both wanted that done.

“The ceremony was precious; I think each individual who got up there and spoke did it eloquently and with great detail of thanking us and knowing what we went through,” she continued. “They made it clear that they recognized that body as not just a body, it was someone’s mom, dad, aunt, uncle, sister, brother, and that meant a lot that they pointed that out.”

Augusta University

Augusta University