Retired Col. Gary Steele didn’t set out to be a pioneer at the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, but by the time he finished his collegiate career, he was just that.

Steele was the first Black student-athlete to ever to play varsity football for the academy. He was also the first Black student-athlete to ever receive a varsity letter in football, but it wasn’t until after graduation that it struck a chord with him.

“At the time, I didn’t put any real significance to it because I was just a member of the team,” said Steele. “I worked hard for my position and was willing to do anything to keep it. But after I graduated, when we started having more African American cadets in and playing football, I realized that wow, maybe there was some significance to it.”

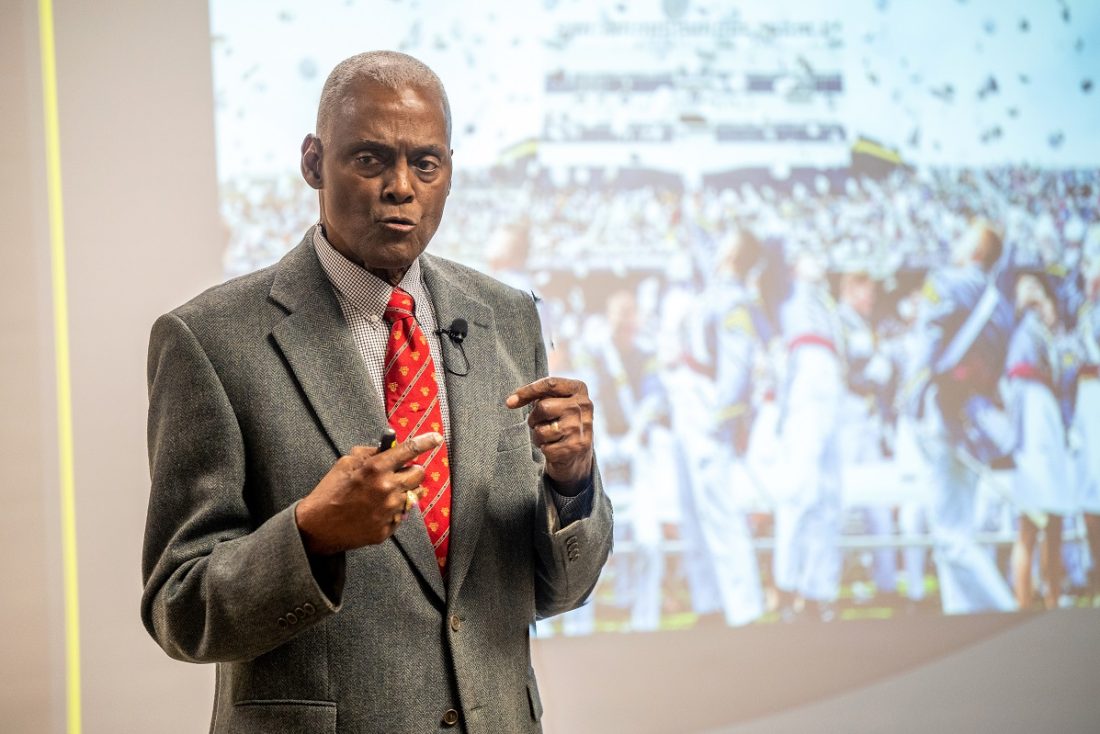

Recently, Steele spoke to a group of about 50 people at the Jaguar Student Activities Center not only about football, but also life in the military and how some of the practices he learned can be applied to everyone. The event was sponsored by the Department of Military Sciences and the Office of Diversity and Inclusion and Multicultural Student Engagement to cap off a celebration of Black History Month.

Steele graduated from West Point in 1970, a time when there were very few Black cadets attending the academy. He said one of the people who helped him get through was his brother, a student a year ahead of him.

He credits his strong foundation and building blocks that were laid by his parents and H. Minton Francis, the first Black cadet to attend the academy. Steele still urges people to recognize those influential people in their lives.

“When was the last time you acknowledged that to them?” Steele asked those in attendance. “Remember whose shoulders you are standing on because they are the people that are going to boost you. Because you’re on their shoulders, you can see a future and see a distant horizon that you couldn’t see without them.”

Steele almost didn’t graduate though. After failing two classes his junior year, he was given a choice to repeat those classes or find a different college to attend. He told his parents he was seriously thinking about going to Penn State, where he had a football scholarship offer. His parents told Steele he could, but his dad said something he’ll never forget.

“Just understand that if you quit, that means West Point beat you.”

Steele went back, took the two classes again and eventually graduated.

“I finally threw my hat up in the air and graduated. It took me five tough years. I did not endure what Milton Francis endured, but there were challenges.”

Steele served in the Army for 23 years and focused on leadership, respect, team loyalty and accountability, knowing that would pave the way for his successes.

He also still lives by words out of the West Point cadet prayer: “Make us choose a harder right instead of the easier wrong and never be content with a half-truth when the whole truth can be one.”

“I try my darndest to live by this because it keeps me straight,” added Steele. “It’s tougher to do the harder right but you will be known by the example you set.”

He also stressed that it’s hard to win at times as an individual, but when coming together, you can be a force.

“When people come together and work together, there’s a lot more solidarity, there’s a lot more power there. You get a lot more done. So Black History Month is a good thing, but American history month for me is even better.”

Augusta University

Augusta University