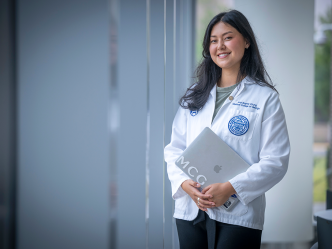

Draped in her white medical lab coat, Peyton McElhone stood at the podium in the Lee Auditorium and looked out at a room full of peers and strangers. Her voice cracked as she began to speak.

Two years ago, she lost her grandfather and a few months later, her grandmother. Both donated their bodies to science, and the pain and incomprehension of their decision haunted her since. She, perhaps better than most of her fellow medical students, understood the heartbreak many others in the auditorium were experiencing at that moment.

But also, perhaps better than the families seated in the audience, she understood the gift those loved ones had given the students: the gift of education through the donation of their bodies.

“I realized that entering the anatomy lab was one of the greatest learning opportunities I will ever be fortunate enough to experience,” McElhone said in her speech at a memorial service for the donors Nov. 1.

One by one, medical students, physicians’ assistants, dentists and nurses all spoke about their experiences working with a donor body and what it has meant to them personally as they learned the intricacies of the human body through the donors. Many students consider them their first patients.

“The anatomy of a cadaver is actually still the best teacher we have,” said David Adams, coordinator of Anatomical Donation Services in the Department of Cellular Biology and Anatomy.

“Even though we’re all made up of basically the same components, there’s a lot of differences and anomalies. That’s the reason that medical schools still use cadaverous material. They still use the textbooks and computers, but we use them as a combined force, so to speak, or a combined unit. Mainly because of the fact of the anomalies, and there’s no way a computer can configure all that. There’s just too many.”

The history

Early donors to the medical school weren’t exactly voluntary. Many a local ghost story recounts the legend of the Resurrection Man, whose given name was Grandison Harris. In 1852 and until the 1960s, it was illegal to dissect a human body unless it was an executed criminal or someone who died in a mental institution.

“Because of the fact that they have not contributed to society, they have taken from society, they have drained society,” Adams said. “So at the point of death, they were used (as a way to give back).”

But it wasn’t enough to meet the school’s needs. So in 1852, the seven faculty members joined together and bought a slave, Harris – and after Emancipation, hired him – to dig up freshly buried bodies from the city’s poor black cemetery.

Harris died in 1911, and for a while, his son followed in his footsteps. Adams isn’t sure exactly what the school did after that to procure bodies for students to study. Records show cadavers were received from the Reidsville State Prison and Central State Hospital in Milledgeville, Adams said. But the law restricting human dissection remained in place until the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act was established in 1968. The act gave people the ability to gift their organs to living persons who needed them.

The gift

Adams took over the anatomical donation program in 2002. Since then, fortunately, there have been enough donations to meet the current needs of the students. On average, the school receives between 100 and 150 anatomical donations per year. But in the event of a shortage, Adams has worked out an agreement with schools such as Maryland State University to receive some of their overages.

“Every year I kind of worry about that because what happens as we go along and continue to evolve as a university, with these particular groups adding more students and that group’s adding more, so that really keeps us having to work out that balance,” Adams said.

Those who wish to donate are registered prior to death. Adams’ office is contacted within four hours of death so that proper refrigeration storage can occur. If the donation is accepted, Adams, a certified funeral practitioner and licensed embalmer, preserves the body for long-term storage.

“It’s a different process than a funeral home, somewhat,” Adams said. “We’re doing a much better job than (funeral homes) are because where they’re just doing it for days, more for sanitation purposes, most of our bodies have to be used for a year or longer. So we’re using a different type of chemical, and we use a little different skill as far as the dissection process. It’s not that we’re better. We’ve just figured out the way to do it to make it work for us.”

The lesson

Standing at the podium during the service, physician assistant student Bibiana Garcia described her feelings as she spent a year studying her donor. She learned, she said, “how to decipher the complex web of muscles, nerves and blood vessels that allow us to work and study, enjoy a meal, play with our kids, and dance like no one is watching.

“But after all of these hours in class and lab, and staying up way too late in the library, there are so many questions that we didn’t get to answer about our first patients. What made her smile? What was his favorite story to tell? What accomplishments were they proud of?

“Who were they … really?”

Questions like these, swirling in the minds of students as they spent hours poring over the inner workings of their donor and learning the intricacies of that one person who in life, they didn’t even know, causes students to bond with their first patients.

That bond is something that has fascinated Adams since he started organizing the memorial service in 2005.

“You’re seeing someone in front of you that has given everything, right up until the very end. So that makes you appreciate that aspect of it, and then I think that bond starts to grow. I don’t think you realize it. I think it’s just something that evolves over a period of time that you’re, you know, that you’re here.”

The students only know their donor as a case number. Many of them make up their own names for their donor. The real names are only revealed as they’re read at the service and even then, students won’t know which name belonged to their “patient.”

Following the service, the donors are cremated. Their ashes go home with their families or are interred at Augusta University’s Cinerarium.

Student after student tried to put into words for these families the gratitude they felt and the significance of their loved ones’ sacrifice. Though they didn’t know their names and wouldn’t know their families, their first patient would live on in the memories of these students. The knowledge they gleaned from them will go on to touch the lives of every patient they help during the course of their future careers.

This year of anatomy behind her, McElhone shared with the grieving families what she really learned this past year: that she finally understood what her grandparents had selflessly given.

“So in addition to my own unending gratitude, I would like to leave all of you with what I discovered on my own journey to learn what it means to donate your body. As a teacher in the anatomy lab, it means you get to be inspired by the great joy of watching others learn anatomy. As a student, working with a body donor, it means you offer a new generation of health care professionals a once in a lifetime opportunity. And finally, as a granddaughter of a body donor, it has meant that I have now found closure in what I understand is the most selfless gift of all.”

Augusta University

Augusta University