In early 2005, Chris Han abruptly woke up to a pounding on his bedroom door. Half asleep, he opened the door only to hear the news no soldier wants to hear.

His best friend, Jae Shin, had just been shot.

As an infantry soldier, 19-year-old Han had already experienced plenty during the Iraq War.

Part of a Stryker Infantry Battalion, his platoon was once called up as a quick reaction force to back up a special operations team to successfully combat a foe. Another time he and his unit drove through the night with their vehicle lights on, hoping to attract enemy fire. The goal was to identify and eliminate any threats, creating a safe path for a non-armored convoy that would later travel on that road.

None of these frontline experiences, however, were as tough as learning that his friend had been shot.

» Related: Army coins are a military tradition brought to Augusta University.

Still a little disoriented following a 24-hour mission, Han couldn’t believe the soldier who was delivering the news.

“Dude, that’s not something you should joke about,” he told the man standing at his door.

Angered by the news and perhaps still in denial, Han shut the door on the soldier’s face and went back to sleep. An hour later, he woke up again. Trying to process what he’d heard, he decided to go to his friend’s room. There, he found Shin’s roommate crying.

“I saw Shin’s uniform,” he said. “It was cut up into pieces. It was all bloody.”

Han, a six-foot-three-inch man, broke down.

The child of a single mother, he had grown up without a father figure. As the oldest male sibling, he took up that role instead. He wanted to go to college but knew his mom would never be able to pay for all three kids to get an education. He decided he wouldn’t pursue a degree just yet so that his siblings could. To help his mom financially, he joined the military out of high school.

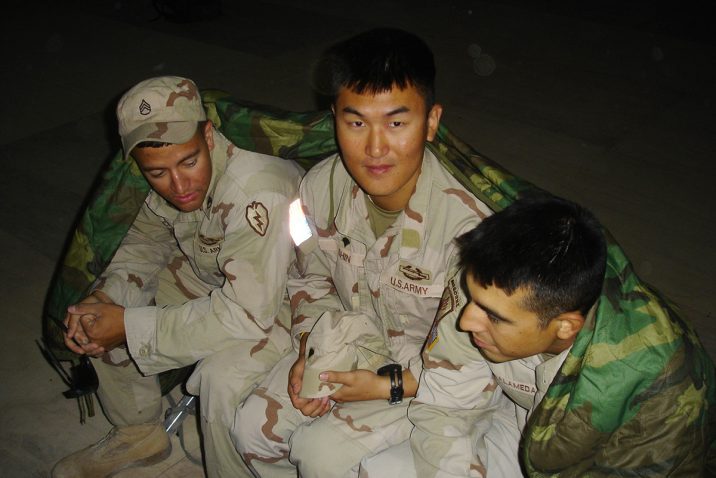

It was in his Army unit that he met Shin, who like him is a Korean descendant. A few years older than Han, Shin took his new friend under his wing. They did everything together. Shin would even go out to buy Han some food. Han, in turn, filled the void he had in his life. For the first time ever, he had an older male figure to look up to.

“He treated me like his little brother,” said Han, a second-generation Korean American.

Their bond grew so strong that Han began to fondly refer to Shin as “Hyung,” a Korean word meaning “older brother.”

Deployment didn’t change that relationship. Although they were in different platoons while in Iraq, they always found time between missions to eat together. Because working out was the only thing soldiers could do for fun in the middle of an all-out war, Han and Shin tried to coordinate schedules to see each other at the gym. And just like brothers who at times make silly bets, they had a bet of their own. They wanted to see who could bench press the most weight before they returned home together.

That bet was over now.

The bullet that stained and shattered Shin’s uniform could have carved a hole in Han’s life once again. The fear of having his older brother, his best friend, yanked away from him was just too much to process in words. Hence, the tears. Han was so shaken that he had to be taken out of missions for the next two weeks. As a frontline soldier, his mind had to be in the mission. Otherwise, mistakes could happen, and in a war, even the littlest one could cost lives. Although nothing in Han’s life had prepared him for the moment he saw his brother’s uniform, what would come out of it would prepare him for life.

The essence of leadership

Shin was lucky.

The bullet that injured him pierced through his right forearm, passing in between the radial bone and the ulna, and stopped on his vest. He survived but had to be sent to a medical facility in nearby Qatar for surgery and recovery. From there, he was sent back home on a two-week leave to spend time with family.

Han waited for Shin to come back. He wanted to know how his friend was doing. Would he be fully recovered?

But two weeks passed, and Shin didn’t return. Han was a little upset but didn’t think much of it. Maybe his friend decided to stay home a little longer. Surely, Shin would come back.

But another week went by.

And another.

And another.

Those last three weeks had been particularly tough for Han because his unit had lost four people. Not having his older brother around to help him cope with the situation made him feel lost. Even though he was surrounded by his fellow soldiers, he felt lonely. Maybe Shin wasn’t coming back, after all. If so, Han needed to at least hear a word from him.

“Hey Hyung, hope you are doing all right,” he wrote. “Shooting an email because I miss you. I’m having a hard time being out here by myself. I was wondering when you’ll come back. Hope to hear from you soon.”

But Han never got an email back.

After two more weeks of waiting, Han was sitting in a dining area, getting ready for a mission. Food was one of the few things he didn’t need to worry about. Soldiers got plenty of it. Eating good food brought Han some comfort — if there is such a thing in the middle of a war.

But that day, as he was working on his big omelet enjoying a quiet moment before his mission, he was interrupted by a blow to the back of his head. The slap was so hard that Han’s head tilted forward and downward and his face almost dipped into his food. How dare somebody interrupt this sacred moment? Han was furious.

“So I turn around to confront whoever did that, and it was him,” he said. “Shin was standing there.”

As much as Han wanted his friend to come back, he knew Shin had the option of staying home after being wounded in action. Then why was he there? Why would he leave his family and long-time friends behind and go back to the frontlines in Iraq, running the risk of not only getting injured again but perhaps being killed?

“The only reason why I’m back here is because you sent me that email,” Shin said.

Han broke down once again.

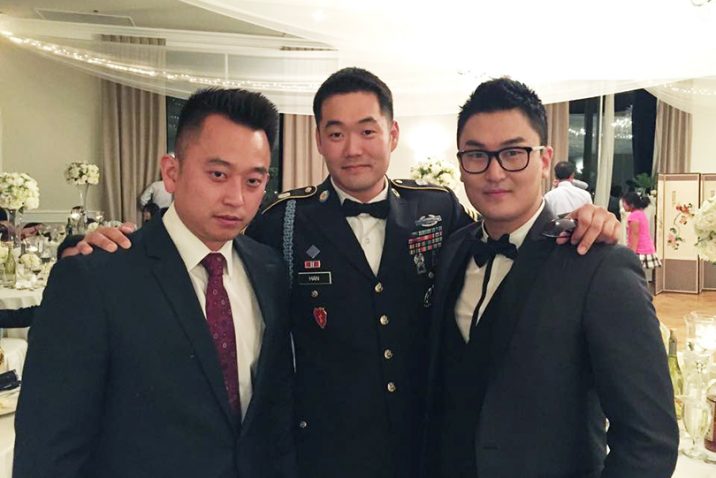

Shin had come back for him. He was willing to risk his life just to stand by his little brother. Han perhaps didn’t know it at the time, but that moment would impact all facets of his life — and the lives of others.

“That’s something I will be forever grateful for because that’s a prime example of selflessness,” he said. “Good leaders always put the mission and their soldiers above themselves. If your soldiers can see that you are like that, then they will follow you into combat and risk their lives with you.”

What he learned from Shin that day would outlive his experiences on the frontlines — a lesson he would always strive to teach others willing to listen.

A web of good will

After returning from Iraq in 2005 and working for some time as a security escort in the Korean Demilitarized Zone, Han was back in his home state of California. Now stationed in Los Angeles, about 100 miles from his native San Diego, Han found himself in a different kind of battle.

There, he met many troubled teenagers who had nobody to lean on. They felt lonely — an internal emptiness he knew all too well. Some were gang members, others came from struggling families and a few thought their lives were just not worth it. Han saw potential in them. They were smart and they were physically strong. He knew that what they needed was a mentor to guide them, to show them they mattered. An experienced Muay Thai and Jiu Jitsu fighter, Han brought them to his gym and took them under his wing. He wanted to do for them what Shin had done for him.

“I treated everybody that wanted help as kind of a little brother,” Han said. “If they showed me the effort, that they wanted to become better as individuals, then I would go out of my way to help them.”

Perhaps for the first time ever, those teenagers found meaning in life. They were taught discipline; they were given a foundation on which to build. So they began to thrive. They stopped getting into fights (Han had made it clear to them that if they ever used anything he’d taught them to prey upon others, he’d kick them out of the program). They were even attending school regularly.

At every training, Han would push them to their physical and mental limit. He wanted them to experience how exhaustion could persuade them to quit. He wanted them to support one another when they couldn’t take it any longer. He knew that shared experience would create a bond among the teenagers. He had experienced that himself on the frontlines. Soldiers become family in the crucible of combat — like him and Shin. Fighting a battle of their own, the teenagers accomplished the same. Through martial arts, they replaced the streets with a family-like environment. They felt safe. They felt like they mattered.

From 2008 to 2011, Han gave those troubled teenagers a purpose in life, and that purpose gave them a life. Some of them joined the Army, some went to college and some even opened their own businesses. Han has impacted so many of those teenagers that he was awarded the military outstanding volunteer service medal — a recognition given only to service members who went above and beyond to help their communities. But Han doesn’t just credit himself for his impact on society.

“It goes back to how Shin came out and looked out for me. I mean, he impacted my life,” he said. “It’s like a spider web kind of effect. One person does this for you, and that impacts you. Hopefully, one of the guys I helped will do the same thing.”

Good will comes around

In 2013, Han transferred from infantry to military intelligence and went to Monterey, California, to get an associate degree from the Defense Language Institute studying Pashto. After graduating, he became a cryptologic linguist and found his way to Augusta in 2015, working for the NSA at Fort Gordon. There he was put in charge of leading a platoon of 44 soldiers. When he took the lead, his platoon had the lowest morale and worst physical fitness score average in the company. Han knew the soldiers lacked direction. They had nobody to look up too. Just like he had cared for his little brothers in Los Angeles, Han took these soldiers under his wing.

One time, two of his soldiers decided they wanted to get their bachelor’s degrees at Augusta University and join its ROTC program. Han assisted them with their applications, writing them a letter of recommendation and even taking them to see the battalion commander for help. The effort paid off. The two of them were accepted at Augusta University. Caring for all of his soldiers like this and treating them like family increased their morale. In a short time, his platoon had the highest physical fitness scores and the highest number of reenlisted soldiers.

After his two soldiers were accepted at Augusta University, Han began to think about applying as well. He would only need to study two more years because he already had an associate degree. With a college diploma, he could become a commissioned officer and have a shot at higher ranks within the Army. He had waited for an opportunity to get a college degree since he joined the Army at 18 to help his mom raise his sister and younger brother. Excited to finally be able to attend college full time, Han applied to join Augusta University and its ROTC program through the university’s Degree Completion Initiative, a collaboration with the Department of Defense. The two soldiers he had helped apply for the program were still there. This time, it was their turn to give him support.

“If you help your soldiers out, and you take care of them, they will come around and take care of you,” Han said.

Han was not only accepted at Augusta University in the fall 2017 but also received the competitive Green to Gold Scholarship with the active duty option. He would get all of his tuition paid for, and he would remain on the Army’s payroll. Han was one of only 200 soldiers nationwide who received this scholarship.

Perfect may not be enough

At Augusta University, he continued to make his mark. He brought with him more than a decade of experience in the Army, but more importantly he also brought with him the altruism he had learned from Shin. After only one year at the university, he became the commander for the Jaguar Army ROTC Battalion.

“Cadet Han is the epitome of a nontraditional student,” said Lt. Col. Danielle Rodondi, chair of the Department of Military Science in the College of Science and Mathematics at Augusta University. “He’s a mentor, he’s a coach and he’s a teacher. He has a lot of pride in what he does.”

Now in his senior year, he was designated a Distinguished Military Graduate, which includes only the top 20 percent of senior cadets in all 278 Army ROTC programs in the country. This ranking follows the Army’s order-of-merit list, which analyzes a cadet’s grade point average as well as performance on a physical fitness test, ROTC training and Advanced Camp. The Augusta University ROTC program had two other cadets ranked among the top 20 percent.

“This is a great program,” Han said. “Our leadership is really committed to producing the best quality officers to serve our nation.”

Han also excelled at Advanced Camp, the final evaluation Army ROTC cadets go through before starting their senior year in college. Held in Fort Knox, Kentucky, Advanced Camp tests a cadet’s leadership, rifle marksmanship, physical fitness and tactical and technical skills. Cadets who pass this evaluation have the full package to lead soldiers into battle.

For about three weeks, Han and more than 500 cadets from all over the country stayed in the woods, running mock missions such as ambushes, raids and reconnaissance missions. Every night at 8 p.m., they would receive their mission for the following day. They had between then and 4 a.m. to plan their actions and get some sleep (sometimes in the rain). Throughout the night, they would have three or four cadets pointing guard at all times. By 5 a.m., they had to be ready to go.

“There were really tough moments where everything kind of sucks because you’re just tired, you’re dirty, you haven’t eaten a lot,” Han said.

Having experienced the Iraq War on the frontlines, Han knew how to operate in that environment. What had kept him going then and what kept him going now were the relationships with his comrades. With 15 years of military experience and 11 in infantry, he was the oldest of his 32-cadet platoon. As he’d done many times before, he would extend a helping hand to the other cadets who had questions or were struggling with a task. Through his leadership, he helped create a positive environment.

“Our platoon actually became like a family,” Han said. “I became the group’s older brother kind of figure.”

At the end of Advanced Camp in August, Han’s altruism and perfectionism were rewarded. He was recognized with the top cadet award, given to the best cadet of each platoon. He was also one of only nine cadets chosen to meet with the Secretary of the Army Dr. Mark Esper for an informal lunch, in which they ate the same ration soldiers eat in combat. In September, he was selected out of 18,000 ROTC cadets all over the nation to be featured on the Army’s website.

“I don’t think there’s anything he can’t accomplish,” Rodondi said. “I really don’t.”

As the commander of the Jaguar Army ROTC Battalion, Han also wants his fellow cadets to succeed. In the same way he strives for perfection, he demands that of others. He wants cadets to get things right. He wants every field training to be perfect. If they are not, he complains that the exercise was not up to his standards.

“You have to have a little bit of that perfectionism as an infantry soldier because you could get killed if you are not doing things exactly how they should be,” Rodondi said.

And even if you are, you could still get killed. Han knows that well because he carries that experience on his left wrist. A one-inch wide metal band bears the names of four of his fellow soldiers who died in battle. One of them was killed in 2007, after Han had already left Iraq. When he heard the news, he couldn’t believe it.

“He was built like a tank — 240 pounds of pure muscle,” he said. “He was hit by a sniper, and that kind of gives you a wake-up call that [nobody] is invincible. Even the most tactically sound and physically strong individual can also be killed.”

Han wants the other cadets to understand that. Now, they are his family — his little brothers and sisters — and he is looking out for them. As their leader, he knows it’s his responsibility to get them ready for combat and to prepare them to lead soldiers into battle. He doesn’t want them making any mistakes that can get themselves or others killed. He wants them to be perfect every single time.

By being a perfectionist himself, he leads his fellow cadets by example. He has earned their respect and trust, and they now follow him. He taught them the importance of treating other soldiers like family — a lesson his older brother Shin taught him. As he had done in the past in other places, with other families, Han’s actions at Augusta University may one day save lives. He is the leader that any soldier would be lucky to have on the frontlines.

“I would follow him any day,” Rodondi said. “He’s just all around an amazing person. I look up to him.”

» Related: Army coins are a military tradition brought to Augusta University.

Editors Note: The Department of Social Sciences was incorrectly identified as the Department of Political Science in a Nov. 6 photo caption of Chris Han.

Augusta University

Augusta University